Class News

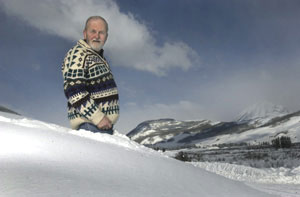

Bruce Driver '64 retires

Man of many talents, one calling

One-time rock singer Bruce Driver a key player on environmental front

From the Denver Post, April 11, 2004

As a boy growing up in the 1950s in Montclair, NJ, he could see the Empire State Building from the roof of his family's house.

A businessman's point of view was closer to home for the future environmental crusader and rabble-rousing adviser to Republican congressmen.

His father turned a small business into an international heavy-industry corporation listed on the American Stock Exchange, with 750 employees who blended metals into electrical wiring for appliances.

The youngest of five children, Driver, now 61, expected to follow his conservative family's footsteps into the metropolis - to Wall Street - maybe riding in a Rolls-Royce the way his parents did later in their lives.

That perspective never left him, and it has made him an astute negotiator who helped persuade Xcel Energy to invest $211 million since 1998 in cleaning up its Front Range air pollution emissions.

His bargaining chip, he said, was that Xcel might not be able to pass on those costs to customers after deregulation.

"I don't see people on the other side of an issue as evil people, never have," Driver said. "They're trying to make a buck, or to make sure people have enough water or power, or that their employees have jobs.

"You can't fault them for that, but you can give them sound information so they can make decisions they can live with."

Driver has taken a lot of turns along the way to heading up Boulder-based Western Resource Advocates, one of the top nonprofit environmental policy and law organizations in the country.

He flirted with business, law, politics and even music. He gave music a shot in the late 1960s, as the lead singer of Rhythm Method, a bar's house band that had followed immediately after future Rock 'n' Roll Hall of Fame inductee Bob Seger.

After playing there three nights a week for almost two years, the band was catching on and Driver had to decide whether rock 'n' roll or law was to be his calling. He chose the latter.

"I had to decide whether to go on and grow up," he said.

Soon after, he said, he had a front-row seat to witness the Republican Party losing its hold on the political high ground on the environment.

In 1973, armed with Ivy League degrees in political science and business and a law degree from the University of Michigan, Driver worked on Capitol Hill as an adviser to Republican members of the House subcommittee on the environment.

"Overnight I watched the Republican Party lose its moorings on environmental issues," he said.

It happened this way, he said:

Democrats still had a New Deal mentality: Every dam, every highway, every coal mine was sacred if it created a few jobs.

Richard Nixon, he said, had started out as one of the best environmental presidents this country had known - backing efforts for stricter water and air pollution regulations. Nixon also rolled out 36 pro-environment proposals and proclaimed the first Earth Week in April 1971.

But as Nixon's troubles mounted in 1973, the powerful big-business right wing of the party pressured Nixon to back away from many of his regulation-focused policies in exchange for their help to stave off impeachment, Driver recalled.

His own crusade to improve surface-mining laws for the environment was caught up in the crossfire, and his job went down with the GOP's environmental agenda.

"I watched the soul of the Republican Party, before my very eyes, shift for a president that was as green as the Democrats ever would be," said Driver, who also worked for Democrats in Washington later in his career.

But Washington, like Wall Street, was not a suit that fit Driver well, he said.

"In Washington, the coin of the realm is status," he said, wearing comfortable shoes and wrinkled slacks as he stretched out at his desk facing a massive window splayed with evergreens in Boulder.

"If you're not in your office by 10 in the morning every Sunday, you lose a little status. I guess I don't care about status."

During the Carter administration, Driver was a lawyer for the Federal Energy Administration, traveling from state to state testifying before public service commissions on effects of rates on consumers.

But he had Colorado on his mind.

He had visited a friend in Crested Butte in 1970. He bought two vacant lots in town for a total of $10,000. He traded them for a cabin across town, which he sold for $50,000 in 1984, he said.

"It was always a special place to me," Driver said of Crested Butte, where he still owns a home and spends as much time as he can. "The topography is so special, the mix of people is special. All the issues I had ever felt passionately about - water, mining, energy - they were all issues there.

"I always knew I would play out my string in Washington, and then move out here."

He did that in 1985, leaving Washington to become the scholar- in-residence for the Western Governors' Association. As part of the job, he published a groundbreaking book, "Western Water: Tuning the System," in 1986.

The book, controversial at the time, argued that the environment deserved water just as much as people do. Today, that thought is mainstream, Driver said proudly.

Eric Hirst, chairman of Western Resource Advocates' board, didn't know what to make of Driver when they met in 1992.

As laid back as Driver tends to be, he can quickly blow into a tornado of ideas and work, Hirst said.

Hirst was a visiting fellow at the law and policy center, then known as the Land and Water Fund of the Rockies, 12 years ago. He was on loan from the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge, Tenn., office, to learn more about power efficiency and conservation from Driver.

Driver and Hirst worked on papers and proposals together.

"It's amazing we didn't kill each other," Hirst recalled.

If a project was due, Hirst would be the steady tortoise, working consistently and patiently as if putting together a puzzle.

"Bruce liked to think about things for a few days, then stay up all night, rushing right up to the deadline, and it was always perfect when he got it done," said Hirst.

"He drove me crazy."

But Hirst is quick and proud to say that he is pleased Driver has built the law and policy center in his own image.

"Bruce is smart and thoughtful and if you look around, those are the kinds of people he's hired," Hirst said. "We've had amazing luck keeping good people, and it's not because of the money we pay. They're there because they believe in the work and because of Bruce, I think."

Asked for an example of Driver's commitment, Hirst fumbled through several examples, then settled on one.

Just about every year, Hirst said, the board gives Driver a bonus for exceeding goals and managing the budget prudently.

"Every year he signs that bonus right back over to the budget so he can use the money for his staff," Hirst said. "A lot of people are dedicated to their work, but not many of them will take money out of their own pocket to support it."

Driver thinks he has a weakness as a boss, however.

He tends to be soft, he said.

A couple of years ago, with donations at low ebb, the bottom line was bleeding red and Driver knew a couple of positions would have to be cut from the payroll.

He told the employees a few months in advance that their jobs would be gone at the end of the budget year. Morale in the whole office was awful for months, he said.

"Sometimes you should just do things quickly and get them over with," he said. "I learned that."

Driver will retire in July as executive director of Western Resource Advocates.

His replacement, Jim Martin, director of the Natural Resources Law Center at the University of Colorado, is an old friend and an admirer.

"I know he has worked incredibly hard, and he deserves the break," Martin said Thursday.