Class News

Howard Gillette '64 — His book reviewed by the Wall Street Journal

Be True to Your School

At an otherwise beer-soaked party, teetotaler John Ashcroft strummed guitar and sang with his similarly sober roommate.

Book review by Marissa Medansky

The Wall Street Journal

July 27, 2015

When Howard Gillette Jr. arrived in New Haven, Conn., in September 1960 for his freshman year at Yale, the social, cultural, and political upheavals that we call the Sixties had barely begun. Ensconced in the university’s Gothic castles, Mr. Gillette and his fellow members of the class of 1964 read classical literature, wore jackets and neckties to meals, and obeyed strict curfews governing residential life — boys caught with female visitors could be expelled. “We missed the Sixties,” one student of that era would reminisce almost a half-century later.

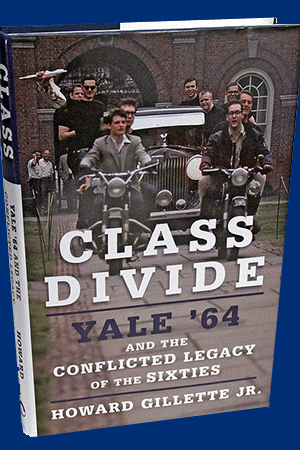

Mr. Gillette challenges that claim in “Class Divide: Yale ’64 and the Conflicted Legacy of the Sixties,” for which he interviewed more than 100 of his classmates about their time in New Haven and their lives after leaving the quad. “While most did not join the countercultural revolution that materialized shortly after they graduated,” he writes, “these men nonetheless broke the expectations and norms of earlier graduates.” The author, an emeritus professor of history at Rutgers, also examined old campus newspapers, reunion books, and other memorabilia, and his research has brought some charming anecdotes to light: As head of the campus newspaper, future Connecticut Sen. Joseph Lieberman orchestrated a student protest mainly so his reporters could cover the story. At an otherwise beer-soaked party, teetotaler (and later attorney general of the United States) John Ashcroft kept himself occupied strumming guitar and singing parody songs with his similarly sober roommate.

But Mr. Gillette’s chief purpose is not simply to highlight notables (in addition to Mr. Lieberman and Mr. Ashcroft, the class of ’64 included the Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt, longtime Washington Post editor Robert Kaiser, and Paul Steiger, a former managing editor of this newspaper). It is also to introduce us to dozens of other lesser known Elis who went on to varied careers as conservative policy makers, clergymen, radical activists, and rabble-rousers. He suggests that this “collective tapestry” adds up to “a picture of not just a class but a nation divided.”

Most of the thousand freshmen who stepped through Yale’s gates in the fall of 1960 — all men, as would be the case until 1969 — came from well-heeled Protestant backgrounds. Just nine members of the class were black; more than 60 had attended prep school at either Andover or Exeter. Their plans for the future “were formed by past tradition,” Mr. Gillette observes. Raised by the men in the gray flannel suits, the class of ’64 believed that the norms of their 1950s childhoods would govern their adulthood in the 1970s and beyond. Many set their sights on careers in banking, law, or medicine.

When they left Yale, though, their world shook. The Vietnam War escalated in 1965, and over the next few years some went off to fight or, like Mr. Kaiser, report on the conflict. Overall, Mr. Gillette writes, 40% of the class would serve in the military. Although some went to Vietnam eagerly, Mr. Gillette cites one 1989 survey in which 70% of respondents from the class described the war as a mistake. Robert Musil, who joined ROTC as an undergrad, eventually helped lead a group for conscientious objectors. Football player Jack Cirie served two tours of duty with the Marines but later spent time studying “energy training” at the Esalen Institute “to release the grief he carried” from the war. Their classmate Thomas Powers would examine the era in a 1973 book, “The War at Home.”

Over the years, many members of the class found their lives headed in unexpected directions. James “Gus” Speth threw himself into the environmental movement (he would later work in the Carter administration and helm Yale’s graduate school of forestry). William Duesing experimented with communal living, tried LSD, and joined an art collective. Alexander “Sandy” McKleroy spent time at a Tibetan ashram and now considers himself a part of the Occupy movement. Robert Ball came out as gay, then moved to Montana to become a sheep rancher. Mr. Gillette surely has chosen the most compelling examples from his pool; a survey taken at his class’s 10th reunion revealed that “fully one-third were working as doctors or lawyers.” Certainly some members of his class ended up in the Wall Street corner offices that their fathers once occupied.

“Class Divide” is organized thematically, so Mr. Speth’s story appears in a section on environmentalism, Mr. McKleroy’s in one on religion and Mr. Ball’s in one on sexuality. Each chapter profiles figures on opposite sides of an issue. The section on civil rights, for instance, contrasts Stephen Bingham and William Bradford Reynolds. Their college years coincided with the passage of the Civil Rights Act; Martin Luther King Jr. received an honorary degree at their graduation. But while Mr. Bingham became a radical (and later fugitive) embroiled with a scandal involving the Black Panthers, Mr. Reynolds served as an assistant attorney general in the Reagan administration, where he denounced affirmative action and similar race-based policies.

Mr. Gillette includes short biographies of so many of his classmates that the book is overwhelming; for readability’s sake, some whose lives receive little more than a paragraph of attention might have been cut altogether. What unites all of his subjects, Mr. Gillette believes, is that “they did not remain on the sidelines.” During Mr. Ashcroft’s confirmation hearing to serve as attorney general, his classmate, Mr. Lieberman, voted against him. Both, however, came to Washington motivated by a sense of action that “Class Divide” attributes to the enduring influence of the Sixties. Mr. Gillette is especially fond of citing a Yale Daily News op-ed that Mr. Lieberman penned as a senior, which outlined his intent to spend several weeks working for civil-rights causes. “I am going to Mississippi,” he wrote, “because there is much work to be done and few men are doing it.”

Here follows a letter to the editor of The Wall Street Journal prompted by the above WSJ review.

Yale: A Weather Vane Of Change in America

Howard Gillette’s book on the Yale class of 1964 focuses mainly on its post-graduation years.

Letter to the editor by Lewis E. Lehrman

July 30, 2015

Regarding Marissa Medansky’s review of Howard Gillette Jr.’s “Class Divide”:

Howard Gillette was a fine student in the European history class I taught at Yale in 1960. His book on the class of 1964 tells an important story about that year’s class, focused mainly on its post-graduation years.

Your readers will surely be interested in Daniel Horowitz’s book “On the Cusp: The Yale Class of 1960 and a World on the Verge of Change,” which focuses more on the sociology of the class in 1956, and how these same Yale undergraduates of the class of 1960 met the challenges in the subsequent decades.

As I know both of these authors, I was impressed by the fact that Mr. Horowitz’s book complements that of Mr. Gillette.

Read the Philadelphia Inquirer book review of "Class Divide."