Class News

Bob Kaiser '64 on Dodd-Frank

Bob Kaiser's new book Act of Congress was reviewed in The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times. Here are those reviews.

How a Bill Becomes a Mess

A step-by-step look at the gruesome business of legislating, taking the 2010 Dodd-Frank bill as a case study

Book review of Robert Kaiser's book Act of Congress

The Wall Street Journal

May 10, 2013

Congress is dominated by intellectual lightweights who are chiefly consumed by electioneering and largely irrelevant in a body where a handful of members and many more staff do the actual work of legislating. And the business of the institution barely gets done because of a pernicious convergence of big money and consuming partisanship.

That is Robert Kaiser's unsparing assessment in Act of Congress, the latest volume in a growing body of work lamenting our broken capital. The book is ostensibly about the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial-regulation bill. But, as Mr. Kaiser makes clear in his subtitle, Dodd-Frank is merely a vehicle for showing "how America's essential institution works, and how it doesn't."

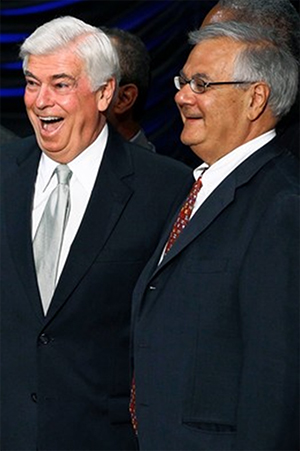

Mr. Kaiser, a 50-year veteran of the Washington Post, secured the cooperation of the bill's namesakes, former Connecticut Sen. Chris Dodd and former Massachusetts Rep. Barney Frank, as well as that of their closest aides. (Mr. Dodd chaired the Senate Banking Committee, Mr. Frank the House Financial Services Committee.) Act of Congress thus offers a detailed "tick-tock," taking the reader through the bill's origins and drafting as well as the unsightly process by which it became law.

What makes Act of Congress a somewhat surprising addition to the Broken Congress genre is that Dodd-Frank would seem to be an example of the system working: Politicians responded to the perceived needs of their constituents, and a bill was passed. Yet, Mr. Kaiser argues, the process itself illustrated what's wrong with Washington, and the legislation ultimately passed more because of luck and circumstance than the wisdom of judicious lawmakers.

Mr. Kaiser depicts the gruesome business of legislating in the wickedly honest fashion only a journalistic veteran, liberated from the restraints imposed on daily reporters, could get away with. Messrs. Dodd and Frank had to fend off the big banks looking to avoid new regulations on one side and liberals pushing for unattainable new rules on the other. Hoping to keep the African-American members of his committee on board, Mr. Frank at one point summoned Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein to Washington to see if the banker could help restructure some debt that the country's largest minority-owned broadcasting company owed to Goldman. Mr. Frank, who is his otherwise voluble self throughout the book, sheepishly told Mr. Kaiser that he "never got into anything specific" with Mr. Blankfein.

Later in the process, Sen. Scott Brown, just a few months after winning his seat in a Massachusetts special election, brings the bill to a standstill when he unexpectedly opposes a procedural vote. To mollify the rookie, Messrs. Dodd and Frank turn to a time-honored Capitol Hill tactic: penning a substance-free letter to give their new colleague some political cover. In this case, they assured Mr. Brown in writing that they aimed to do no harm to financial institutions in Massachusetts.

The legislation only came together, in the end, because Mr. Dodd gave up on finding a GOP partner and pushed through the bill by placating individual Democrats and picking off a few moderate Republicans. In the passing of Dodd-Frank, the public interest — however that might be defined — often took a back seat to money, special interests and political expediency.

It did not help, notes Mr. Kaiser, that many members of Congress are politics-obsessed mediocrities who know little about the policy they're purportedly crafting and voting on. Indeed, it is Mr. Kaiser's frank and often scathing criticism of Congress that enlivens a book that might otherwise strain the attention of anyone not intensely interested in the regulation of derivatives.

When Rep. Lacy Clay, a Missouri Democrat, uses a hearing to ask the vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board if legislation should be considered to replenish the IRAs and 401(k)s of individuals hurt by the recession, you can almost see Mr. Kaiser shaking his head in disbelief. "Someone who understood the vagaries of financial markets would not have made this suggestion," he deadpans. Elsewhere Mr. Kaiser quotes Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid telling reporters that "the details of Wall Street reform are complex." In the next sentence, he writes matter-of-factly that Mr. Reid himself "never really understood them."

Mr. Kaiser shows various politicians robotically stating talking points that are unrelated to the substance of the bill. Republican pollster Frank Luntz advised GOP officials to tag the legislation with the word "bailout," a toxic description in the wake of the 2008 TARP legislation, and that they did. "Why do they have a bailout fund if you're not going to bail people out?" asked Texas Rep. Jeb Hensarling, a Republican, on the House floor. There was no bailout fund, Mr. Frank responded — to Mr. Hensarling and many other Republicans who waved the same bloody shirt — only a fund to "put an institution to death."

In one of the book's most revealing passages, Mr. Dodd is on the verge of striking a deal with Alabama Sen. Richard Shelby, the ranking Republican on the Banking Committee, when Mr. Dodd's cellphone rings and he finds Harry Reid, Bob Menendez, Chuck Schumer and Dick Durbin, the top four Senate Democrats, on the other end of the line. The Democratic leaders told Mr. Dodd to stop negotiating with Mr. Shelby. "There were always those elements in the [Democratic] caucus," Mr. Dodd tells the author, "who thought fighting would be better than getting a bill."

In other words, there were Democrats who would have preferred to have an issue with which to beat Republicans rather than work with the opposition to reach a compromise. That phone call, writes Mr. Kaiser, underlined a fact of modern congressional life: "Most members both know and care more about politics than about substance."

Mr. Kaiser doesn't write off the entire institution. He has a warm, admiring view of Messrs. Dodd and Frank, who are shown correcting the mistakes and excesses of their colleagues. He also finds praise for assorted other members, most notably deal-hungry GOP Sen. Bob Corker of Tennessee, who is willing to anger the more senior Mr. Shelby in an attempt to find a compromise. But they are the exception. "Of the 535 members of the House and Senate, those who have a sophisticated understanding of the financial markets and their regulation could probably fit on the twenty-five man roster of a Major League Baseball team," Mr. Kaiser writes. "Members' ignorance empowers lobbyists and staff."

What makes Act of Congress especially valuable is its detailed portrait of Washington's influence peddlers and, in particular, the powerful aides who script their boss's statements, write the bills and often become lobbyists themselves after leaving the government payroll. When Mr. Brown, the Massachusetts senator, had to be assuaged, it was left to a Frank aide to get up before dawn and draft the letter reassuring him about Bay State banks. And when a dozen liberal senators grow alarmed because a consumer-advocacy group misreads a provision and sends out a press release suggesting that GE Capital is getting a special exemption, it falls to staffers to save the senators from themselves by pointing out the error.

Perhaps most telling was the moment when Messrs. Dodd and Corker traveled together to Central America in their capacity as members of the Foreign Relations Committee. Senate staffers could not understand why the Obama administration was so worried that the Democrat would use the trip to cut a deal with the Republican and thereby weaken the bill. "It was naïve to think that two senators, without staff, would try to work out the bill," explains a Dodd aide.

Big money, small politicians, and the lobbyists and staff running the place: It's hardly a new story about Washington. But Mr. Kaiser names names and spares no one.

Chamber Made

Book review of Robert Kaiser's book Act of Congress

The New York Times

July 11, 2013

The house chamber is largely empty during the electoral college vote count, January 2013

The house chamber is largely empty during the electoral college vote count, January 2013

Congress has long been one of the country's most establishmentarian institutions. Unlike the presidency, which periodically comes under the control of outsiders, Congress rewards sheer longevity, mastery of obscure rules, and inoffensiveness to colleagues. Unlike Supreme Court justices, who live in what passes for monklike isolation by Washington standards, most congressmen circulate among a permanent klatch of pundits and lobbyists. Few who serve more than four or six years can hold out against the sheer brain-deadening blandness this encourages.

It's no surprise this institution would attract Robert G. Kaiser, who grew up in the capital and has spent half a century at The Washington Post. Kaiser's new book, Act of Congress, chronicles the making of the enormous financial reform bill that became law in 2010. Although Kaiser constantly bemoans the lack of civility and rise of petty politicking in Congress, it's clear that at its most functional, the body reminds him of the Washington of his youth, when serious-minded men of good will toiled in the national interest. Financial reform is proof that even in its current, degraded form, Congress can still occasionally serve this higher purpose.

This is what Kaiser intends to show, in any event. What he actually shows is the limits of establishment thinking, of the sort that pervades both Congress and his book. Kaiser tells the story of financial reform through the two figures who guided it to passage: Barney Frank, who chaired the House committee overseeing the financial services industry, and Christopher Dodd, his Senate counterpart. Both Frank and Dodd granted Kaiser frequent interviews while they worked on the bill and encouraged their staffs to do the same. These interactions only marginally advance our understanding of how reform came about, but they do reveal what its architects were thinking. And it's striking to see how self-satisfied they were.

At times Dodd and Frank, along with their colleagues, come across as downright blinkered. Frank complained to Kaiser about a front-page article in The New York Times describing the banks' secret plan to fend off regulation of derivatives, the lucrative financial instrument at the center of the recent meltdown. Frank hated the implication that the banks were setting the terms of financial reform and harrumphed that Gretchen Morgenson, the article's co-author, "is so determined to be negative, she just gets it wrong." But the thrust of her piece closely matched other reporting at the time.

Or consider Frank's staff director, Jeanne Roslanowick, who was skeptical of a new agency to crack down on predatory lending. Roslanowick told Kaiser, presumably with a straight face, that moderate House Democrats were cool to the idea because their constituents weren't interested in it. "If what they were feeling back home . . . suggested the public was crying for an independent consumer protection agency, they would be responding to that," she explained. A neutral observer might suggest that Roslanowick spend less time around bank-funded Democrats. (Polls consistently showed the consumer agency to be enormously popular.)

Throughout Kaiser's book, the policy makers and aides he interviewed adopted a kind of "everybody knows" posture — everybody knows that Morgenson gets her facts wrong, or that the consumer agency would be a flop. Naturally, this mind-set infects the substance of reform. Apparently, no one around Frank or Dodd questioned the utility of extending bank regulation to other large financial firms, a cornerstone of the Obama administration proposal. No one wondered why, if bank-style regulation was the panacea Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke made it out to be, it didn't prevent a megabank like Citigroup from flaming out almost as spectacularly as the lightly regulated A.I.G.

One of the last issues Congress had to deal with before approving the Dodd-Frank bill was Senator Blanche Lincoln's insistence on banishing the banks' derivatives desks to separate subsidiaries. All the key players in reform — Dodd, Frank, Geithner, Bernanke, even Paul Volcker, the legendary former Fed chairman — opposed the idea, which survived only because Lincoln chaired a key Senate committee. The power brokers claimed the proposal was sloppily written and politically motivated (Lincoln, who was from Arkansas, was fending off a primary challenge from the left when she cooked it up). To the extent anyone offered a substantive objection, they said her idea would drive derivatives into the shadows of the financial system, outside the view of regulators.

In fact, the proposal would almost certainly have made the financial system safer, at least once the technical kinks were ironed out. It would have required the banks to pump enormous amounts of money into their derivatives subsidiaries, making them far less likely to go belly up and require a taxpayer bailout. The banks hated this because it would have meant setting aside billions they were otherwise free to speculate with. Yes, there may have been practical reasons to oppose the measure — perhaps it was too much change, too quickly. But Kaiser and his sources seem never to have debated the subject. They simply pronounced it unserious.

Like any good establishmentarian, Kaiser is skeptical of public opinion, and even more so of the politicians who pander to it. His diagnosis of what ails Congress can be summarized as "too much democracy." He laments the huge drop in the amount of time congressmen have spent in Washington since the 1960s, when the government paid for only three annual trips home. (There is no longer a limit.) He echoes Dodd's frustration that too much of what Congress does these days trickles into the press, unlike the back-room dealing of yesteryear, and Frank's concern that the financial crisis ushered in the "greatest breach between elite and public opinion that I have ever seen."

Let's concede that the great unwashed can be ignorant, irrational, and erratic. As Frank tells Kaiser, "The voters are no bargain." Even so, a proposal isn't flawed just because it's designed to win them over. As it happens, the main reason Dodd-Frank has any bite at all is that a variety of political opportunists intervened along the way. Both Geithner and Frank initially signed off on a derivatives bill that was shot through with loopholes. It took public grandstanding by an obscure regulator named Gary Gensler to shame them into toughening it up. (And even then lobbyists later poked holes in what he accomplished.) The so-called Volcker Rule, which makes it hard for banks to gamble with taxpayer-backed money, would not have become law if senators like Carl Levin and the president himself hadn't played to the folks in the cheap seats.

If Dodd-Frank teaches us anything, it's that we need more crass politicking, not less, at least when all the money and influence favors one side so overwhelmingly. Public opinion may not be responsible or dignified, those time-honored establishment virtues. But sometimes it's our only hope.