Class News

"Fabled" Jim Rogers '64 has the last laugh

Last Laugh

Barron's cover story, June 5, 2006

By JONATHAN R. LAING (more about Rogers, and more, and more)

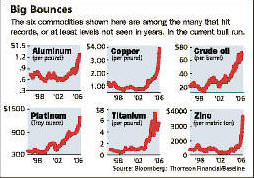

WITH THE PRICES OF OIL AND INDUSTRIAL METALS like copper, zinc and nickel screaming higher in recent months, such observers as Warren Buffett and Morgan Stanley's Steve Roach have proclaimed that commodity markets are in a bubble destined to burst soon.

But Jim Rogers, fabled hedge-fund manager of the 'Seventies and now ardent commodity bull, finds such talk ridiculous. Indeed, he has been pounding the drum for investing in commodities in recent years in numerous speeches and media interviews, even writing Hot Commodities, a book propitiously published in late 2004 that predicted a coming price boom in everything from aluminum to zinc.

Barron's caught up with Rogers on a recent rainy morning as he worked out on a stationary bike in the fourth-floor exercise room of his five-floor mansion on New York's Upper West Side. Bloomberg Radio droned in the background as he talked while occasionally glancing at a laptop computer, perched precariously on the machine's handlebars. "How can anybody say that a bubble has developed in commodities yet" ― brief pant ― "with sugar 80% below, silver 75% below and corn and cotton less than half their all-time price highs?" he huffed. "You can't have a bubble when the media has only begun to pay attention to commodities in recent months after years of disinterest. We're now only in the early part of a long-term commodity price boom that has years to run and will likely see literally dozens of raw- material prices make new highs. Even crude oil and copper have a long way to go, even though they recently set price records."

How long will the surge run? Based on the past longevity of commodity bull markets (Rogers mentions ones that, by his reckoning, lasted from 1906 to 1922, 1933 to 1953 and 1968 to 1982), the current boom could last eight to 14 more years. The commodities-bubble crowd scoffs at that, just as skeptics did when Rogers predicted the current boom a few years ago

COMMODITY PRICE BOOMS, says Rogers, are typically the product of years of underinvestment in new productive capacity ― whether in exploration for new oil or metal deposits, construction of new smelters and refineries or planting of new orange or rubber trees ― in response to low prices. Meanwhile, demand creeps up all but unnoticed until imbalances suddenly erupt and prices surge. Producers ― with the possible exceptions of grain farmers and cattle ranchers ― can't respond quickly because of the long lead times required to finance and build new capacity.

Over the years, commodity prices have tended to surge during periods when the stock and bond markets have labored, exhibiting what modern portfolio theorists call non-correlation with the financial marts. For instance, commodities did poorly during the stock market booms of the Roaring 'Twenties and the post-1982 bull market, while outpacing stocks during the Great Depression and the 'Seventies, Rogers notes.

Recent studies seem to bolster this observation. One, superintended by capital-goods analyst Barry Bannister, now of Stifel Nicolaus, found that over the past 130 years, commodities and stocks have alternated performance leadership in regular cycles, averaging about 18 years. A 2004 study by Gary Gorton of the University of Pennsylvania and K. Geert Rouwenhorst of the Yale School of Management that examined market returns from July 1959 through December 2004 concluded that passive, systematic long investments in commodity futures generated total returns comparable to the S&P 500's, while both asset classes smoked the corporate bond market. Even better, the two academics concluded, commodities were less volatile and hence less risky than stocks over those 54 years. And their lack of correlation with stocks made them worthy diversification tools.

It's no surprise, perhaps, that commodities march to a different beat than stocks and bonds. Unlike their financial counterparts, commodities are hard assets that both contribute to and benefit from inflation ― particularly, unanticipated inflation. Rising inflation hurts stocks by crimping companies' profit margins and consumers' purchasing power. Inflation's fraternal twin, rising interest rates, likewise can savage bond returns by sapping the real value of interest and principal payments.

To Rogers, the past few years have witnessed another changing of the guard; commodities will rule over stocks and bonds for the next decade or more. Inflation will continue to flare and not just because of rising raw-material prices. According to Rogers, new Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke is "an amateur with no knowledge of markets" whose academic work revolved around how nations could avoid depressions by printing more money. And, finally, he throws into this witches' brew the likelihood of a collapse in the dollar as a result of America's accelerating debtor status. Rogers views commodities as the ultimate refuge from these scourges.

FUNDAMENTALS WILL TELL the tale for commodities. Rogers invariably points out in speeches that no major oil fields have been discovered in more than 35 years, nor major new metal-mine shafts sunk in 20 years. And many existing "elephant" oil reservoirs, such as those in the North Slope and the North Sea, are fast depleting. And who can trust the Saudis to tell the truth about their real oil reserves? That leaves the global market depending on production gains in Russia (a "bunch of mafiosi who have probably already reached their peak production level") and such basket cases as Nigeria and Venezuela.

Sure, oil from the Caspian Sea and the Alberta tar sands eventually will hit the market. Wind, solar and geothermal hold promise, as do biomass-generated power and other alternative energy sources. But tapping them will take lots of time and money, warns Rogers.

On the demand side, there's the U.S. consumer, who in the 'Nineties considered McMansions, gas-guzzling SUVs, fancy appliances and ubiquitous electronics a national birthright, gobbling up gasoline, natural gas, electricity, timber, steel, aluminum and lead (for batteries) at a fearful rate. Add to that 1.3 billion Chinese and 1.1 billion Indians ― all largely walled off from the global economy during the last commodities boom ― joining the global scrum for natural resources.

CHINA IS NOW the No. 1 consumer of copper, steel and iron ore, and No. 2 in the use of oil and energy products to feed its industrial maw, which is growing at a prodigious rate of nearly 20% a year. And the torrent of textiles, refrigerators, color TVs and computers aren't just flowing to overseas outlets like Wal-Mart. Burgeoning economic growth is also creating a Chinese middle class aspiring to better meals and more creature comforts. In Rogers' view, it's delusional to deny that competition for commodities will continue to heat up as a result of China's pell-mell rush from a peasant economy to economic giant. Today, there are only 30 million private vehicles on the roads in China, versus 235 million passenger vehicles in the U.S., even though China has almost 4½ times as many people.

So far, the scramble for natural resources has mostly affected energy and metal prices. But Rogers thinks the price boom will soon spread to "soft commodities" (like cotton, sugar, coffee and wool), rubber, lumber and ― perhaps most telling ― grain and oilseeds. Already, lots of corn and sugar production is being siphoned off into ethanol output.

"Future Chinese demand under their 'People First' campaign will be enough to push up prices in these sectors," he says. "In some grains, for example, stocks are beginning to tighten despite global bumper crops in recent years and an absence of major droughts. Despite low per-capita soybean, meat and chicken consumption by worldwide standards, China is already a major importer of soybeans and other grains and figures to get even bigger as diets improve."

Rogers has more than an academic familiarity with global economic and political trends. In the early 'Nineties, he set a Guinness record by motorcycling 100,000 miles across six continents. Then he made a three-year, round-the-world journey between 1999 and 2001 in a custom-modified, two-seat Mercedes, setting another Guinness record by covering 152,000 miles and passing through 116 nations. The trips gave rise to two popular adventure and investment primers: Investment Biker and Adventure Capitalist.

So enamored of China is Rogers that he and his wife, Paige, have even considered moving to Shanghai or Singapore (a bastion of overseas Chinese wealth). They've received visas from Singapore for a trial stay in that city-republic this summer and put their New York home on the market for $15 million. And their three-year-old daughter, Hilton Augusta, is being taught Mandarin by a Chinese nanny. "I'm convinced that China will become the No. 1 economy in the world in 20 years or so, and that knowledge of Mandarin will be indispensable for any child of today," says Rogers.

ROGERS FIRST GAINED celebrity by co-founding the wildly successful Quantum Fund with George Soros in 1973. The hedge fund used gobs of leverage to notch a return exceeding 4,000% over the remainder of the decade, despite a poor stock-market environment. Rogers then retired at age 37, somewhat prematurely as it turned out. Soros' hedge-fund empire grew in subsequent decades, making him a multi-billionaire, while Rogers' net worth, which he declines to disclose, is a fraction of that, although it's certainly not insubstantial.

Yet Rogers has scarcely disappeared from public view in recent decades. Like a sunflower bending its face to the sun, he's long been drawn to the media's glare. He's a frequent guest on financial and news shows on TV, even moderating several financial programs for a time. His books and dynamic style have made him a much-sought-after speaker in the U.S. and abroad. He was also a popular member of the Barron's Roundtable in the 'Nineties, known for his sporty bow ties and touting of idiosyncratic investment ideas like Southeast Asian white pepper (or "peppah" as rendered in his inimitable Alabama accent).

His detractors were often put off by his sometimes apocalyptic predictions and his claims, made after the fact, of having caught just about every global market move from a temporary stock surge in Botswana to adroitly sidestepping Korean shares just before they tanked in 1997. He has long been bearish on the U.S. dollar, though in the 'Nineties that was a losing proposition. As a private investor with no verifiable track record, Rogers was vulnerable to charges of showboating.

ALL THAT CHANGED in the summer of 1998 when Rogers, wary of the then-roaring U.S. stock market, concluded that the future lay in commodities and developed a proprietary index of 35 of them, each with a futures market. They were weighted in line with his view of their relative importance in global industrial and food consumption.

Thus, he included azuki beans and rice in his grain and oilseed category, comprising in all about 20% of what was grandly dubbed the Rogers International Commodity Index, or RICI. Other commodity indexes ignore them. The Rogers Energy sector (crude, heating oil, unleaded gas, etc.) was assigned a weight of 44%, far lighter than the more price-sensitive weighting of over 65% that energy recently commanded in the popular Goldman Sachs Commodity Index. Industrial metals, from aluminum and copper to zinc and tin, have a 14% rating, nearly double the 7.1% weighting given precious metals. The latter is an indication that Rogers is hardly a gold freak. Finally, the index is rounded out by the afore-mentioned soft commodities and livestock.

And now, once again, Rogers is throwing some serious heat. Since its advent on Aug. 1, 1998, the RICI has clocked a total return of 265.59% through the end of April 2006, for a compound annual return of 18.61% over the period. Only the South Korean stock index, the Kospi, of some 50 international indexes tracked by Barclay Trading Group boast a higher return (313.49%) than the RICI over the period. In comparison, the S&P 500 limped in with a 31.81% total return, while the Nasdaq Composite did even worse with just 24.04%. The Rogers Index, with its nearly 266% return, also beat the Goldman Index (up 201.65%) and the 80.81% return posted by the Reuters-CRB Index.

AS ROGERS STARTED the commodity index, he began offering index funds through Beeland Management, a company he controlled. Beeland is his middle name.

The funds were intended to mimic his index and various subsectors of it by buying futures in the underlying commodities at their precise weightings. The bane of individual investors in commodity futures has always been leverage. But instead of posting just the 5% to 10% margins on positions required by exchanges to guarantee performance under the contracts, his commodity index funds put up 100% collateral on the value of the contracts. In fact, the Rogers funds assume that the investor will earn the 90-day T-bill rate on the 90% or so of excess margin, while patiently waiting for the futures positions to work their magic. Money was to move seamlessly between the exchange margin and excess margin accounts. If underlying futures positions declined in value, the excess margin account could be tapped to top up exchange margin positions. In the event of rising future values, appreciation would create extra margin in the exchange accounts. And this could be transferred to the excess margin account.

IT WAS THIS very mechanism that malfunctioned last fall when Beeland's commodity broker, Refco, filed for bankruptcy after apparent malfeasance by top Refco executives was discovered. Some $370 million of Beeland funds' excess margins ended up trapped in an unregulated unit of Refco, rendering Beeland just another unsecured creditor in the bankruptcy. As a consequence, the Beeland funds were shut amid a hail of lawsuits between Beeland and Refco and by investors in the funds seeking recovery of their money and damages from Rogers and Beeland, among other defendants.

Other funds, however, have licensed the Rogers Index. Merrill Lynch offers a RICI Trakr stock (ticker: BUV0) on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange's electronic arm; it has already attracted about $1 billion. Credit Suisse, UBS, Daiwa, Barclay and other banks likewise run commodity pools based on the index. For U.S. investors, the Trakr is perhaps the most attractive vehicle because it qualifies for the favorable capital gains accorded stocks.

In all, some $90 billion in institutional and individual investor money has poured into various commodity index products with the Goldman Sachs index boasting around $60 billion of the total. Hot performance has been part of the lure, to be sure. In addition, the commodity markets have become infinitely more respectable as a result of academic studies, such as the earlier-mentioned Gorton-Rouwenhorst paper, asserting that fully collateralized futures positions shield investors against inflation while offering stock-like total returns over the long haul, though timed to different stages in the economic cycle.

Some observers contend that the advent of commodity index funds, along with the addition of exchange-traded funds based on a single commodity, such as gold or silver, artificially pumped up prices through collective buying. The ETFs purchase physical commodities as money pours in, while the index funds concentrate on futures that are near expiration. The latter activity also boosts "spot" or cash price of commodities, some maintain.

ROGERS FINDS SUCH contentions preposterous. First, he argues, the commodity index funds are minuscule, compared with the index funds that operate in the stock and bond markets. Also, commodities index funds must constantly roll their futures positions forward as their existing futures approach expiration. This relieves buying pressure on nearby futures. The Rogers funds, in fact, buy only futures two delivery periods away from expiration.

Finally, the large commercial interests that trade commodities aren't about to let speculators wrest control of prices. "ExxonMobil can drown all the index funds, hedge funds and other speculators in the energy markets if anyone tries to manipulate prices," Rogers asserts. "It's largely the surging global demand for raw materials that is pushing prices up."

Rogers is the first to concede that the bull market in commodities will have plenty of nasty corrections and volatility along the way. That's the nature of bull markets. Gold, on its way to its record of $850 an ounce in 1980, suffered a 50% correction in the mid-'Seventies, falling from nearly $200 to $100. The Rogers Index itself dipped some 25% in the months following 9/11. Then, it resumed its upward trajectory.

Obviously, a major terrorist incident, a bird-flu epidemic, a global financial crisis or a hard landing in the Chinese economy could trip up the commodities bull. But, according to Rogers, any slide would likely be temporary and offer a good buying opportunity.

None of these events changes the underlying dynamics of the global economy. Supply will remain constrained for some time. And demand won't disappear. Not with China's 1.3 billion people, fired by rising aspirations and epic entrepreneurial zeal, driving the market. Consumption is likely to outstrip supply if only because of the developing world's hunger for a better life.

THE COMMODITY BOOM, like all bull markets, eventually will end in a crescendo of hysteria. The public will feel an overwhelming desire to invest in raw materials rather than stocks or bonds. Financial publications will be chronicling the derring-do of commodity kingpins with the reverence and wonder once accorded the dot-com billionaires. Seemingly insatiable demand for commodities will provoke investment in new sources of supply, but few investors will notice as supply and demand start to come back into balance.

But that day won't dawn for a decade or so, says Rogers, who hopes to be on to the next big thing by then.