Sound Off !

Campus unrest

December 2015

Here are numerous articles commenting on the campus unrest which broke out at Yale in November 2015. These articles are republished here to provide background material for those '64 classmates who wish to further their understanding of the issues and perhaps express their views in our Sound Off! forum.

- Interview with Dean Jonathan Holloway (The New Yorker)

- Opinion piece (The Atlantic)

- Opinion piece by a Yale student (The Nation)

- Peter Salovey at the AYA Assembly

- Peter Salovey on what steps will be taken

- Columns by Cole Aronson, Yale Daily News

- The email from Erika Christakis

- The aftermath: Erika Christakis resigns from teaching (The New York Times)

- Opinion piece (The New York Review of Books)

- Interview with Erika Christakis (The New York Times)

- Debate: Is free speech being threatened on campus? (YaleNews)

For links to more information, see the Yale web page Toward a More Inclusive Yale.

What Divides Us?: An Interview with Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway

The New Yorker

November 15, 2015

Amid the many conversations these past two weeks about racism and free speech at Yale University, one moment stood out. Last Thursday afternoon, hundreds gathered and expressed their grievances about the treatment of students of color to Jonathan Holloway, the first African-American dean of Yale College. Holloway, a historian of civil rights, is at the center of a campus conflict about liberalism and education as well as the meaning of an inclusive community. We spoke to him on Thursday evening about the origins of the protests and their implications for other institutions.

Can you describe what the climate is on campus now?

I can’t speak to the graduate professional students because I don’t work with them. The undergraduates are, well, exhausted. What I think they are feeling is that they are part of something larger than their own existence, with all these rallies happening across the country — that they are living a very special moment.

There’s a sense of excitement about that. They’ve got their eyes on the administration because they got our attention, absolutely, and now they know that the president said we are going to announce some concrete changes.

They’re watching us, as they should, and they’re trying to get back to class. They haven’t been going to their classes for the better part of a week, as they’ve been trying to navigate all this. It’s getting quieter. It’s getting clarified, and we’ll see. The next frontier, frankly, is the faculty, because there’s a growing divide in the faculty about issues of free speech. The faculty are getting one version of the story, frankly, as is most of the country, about the free-speech-raising issue on campus.

The students, for them it’s not about free speech. They aren’t questioning the rights of free speech. You’re hearing this incredible pain and frustration related to the issue of being constantly marginalized, feeling that their speech and their existence simply doesn’t matter. They get that message from all kinds of different stimuli in their life, whether it’s the pop-culture world, whether it’s the stuff they’re learning in classes, or peers who don’t value them and their contributions, or peers who simply think they don’t deserve to be at this place, or that they, relatedly, don’t have the intellectual ability to handle problems — long papers, etc. It’s a lot of this stuff coming together that the students are very frustrated by, and now that it’s getting conflated into a free-speech issue, it’s galling to them.

Can you elucidate how people came to see a conflict between the free-speech issues and the issues that students are actually concerned with?

It happened in the confrontation in the college courtyard, where the video is telling a louder story than anybody else — the video that captured the student yelling at the residential-college master. She looks like someone being uncivil and shouting over the master, and he’s trying to talk about free speech, and she doesn’t want to hear it at all. The video portrays her as having an anti-intellectual and anti-free-speech kind of mindset. Like I said, for these students, that was not the issue. They said, “If you think that this is about an e-mail or about a party people didn’t get into, you’re not paying attention. This is a much deeper and broader, systemic problem, and that’s what we want to talk about today.” On the free-speech thing, there’s plenty of faculty who themselves are either free-speech purists, or who believe deeply in civil discourse and don’t want to disrupt it, or see a friend of theirs being treated discourteously — it could be any number of these things — and feel that the master and associate master have been thrown under the bus, because no one has come to their defense.

The fissure is between the faculty who are upset at the way that the master was treated and, well, the faculty who feel quite differently. That’s a growing issue, and so there are petitions floating around, not yet delivered, but being talked about, that are to support this person or that person, this issue or that issue. We’re nervous — or concerned, I should say — because there are rumblings among the faculty, but this could go in many different directions at any moment. We don’t know what to expect. There are many times in the last week when we thought something was going to zig and it zagged, with incredible speed. That’s the world we live in in these days, with social media and the rallies.

You said the students said that this was not about two isolated incidents, but that they were talking about a bigger context. What exactly is the context that they’re talking about here?

It’s in Yale’s culture, specifically, that’s what I’m speaking to. You have a very privileged university, with a lot of students here of great privilege and a lot without. You’re dealing with a coming together of people from radically different perspectives, and you take, in this case, what we’ve been hearing mostly from women of color, that they’re feeling doubly marginalized, in this very pure-air environment, where their views are discounted because they’re female, or their views are discounted because they’re black or Latina, or their views are discounted because they’re both. People are telling stories of professors presuming they wouldn’t know how to answer a question, while the white students in the seminar got a very different set of reactions on the same issue, where people wouldn’t even engage them, that fellow students wouldn’t make eye contact, wouldn’t talk about them. They’re sick and tired of people saying, “Can I touch your hair? It’s so exotic.” They’re frustrated by the notions of beauty in which they aren’t represented at all.

It’s no single thing. It’s all of these things. Then you also add the fact that, for so many of them, there are too few courses that resonate with their personal lives. This is not to say that everything we teach has to be personal, but when none of what we teach reflects your experience, that’s a problem. You’re getting that kind of frustration as well. Added to the mix are some noted faculty departures. This happens at universities, but there’s a confluence of faculty departures that are signalling institutional inability to retain faculty, unwillingness to retain faculty, or unwillingness to develop faculty. It’s all being read in the way that people are thinking, Gosh, this place doesn’t care. It just doesn’t care.

Are they talking about this in the bigger context of Black Lives Matter, and other protests and demonstrations we’ve seen on campuses across the country?

Certainly students are talking about it to one another, about what kind of moment this is. The trigger was really mostly the local issues, racial crises at Yale. There’s no doubt that these students are being informed by the world in which they’ve grown up, from when they were in ninth grade roughly to the present. Trayvon Martin, Ferguson, Staten Island, Charleston — how many different times in Charleston? — Cleveland. They’ve grown up seeing people their age being killed, with impunity. That’s a burden. That makes managing life quite difficult. Even if you yourself are not in a position of having your mortality threatened, the fact is, you’re living in a world where people are openly debating that George Zimmerman was probably doing the right thing, that Trayvon Martin probably couldn’t have been trusted. Where the news is saying that Sandra Bland was copping an attitude, so she brought it on herself. That’s a hell of a way to understand the world you live in, especially when you’re in college and trying to figure out who you are. Trying to decode that while navigating what the smartphone media is telling you is very hard.

Last week, there was the initial demonstration, where students were voicing their displeasure. I think you said that you were at this rally, and you listened for two and a half hours before you responded to them. When you were listening to them, were they articulating things that you were surprised at? You teach civil rights and African-American history.

That’s the tragic thing. None of this sounds new to me. That’s really the saddest thing of all — that the things that they’re complaining about are old and recurring problems. Part of that is that a college is constantly renewing itself, so new people are always coming in and trying to sort things out. That’s just a fact of college. Part of it is that there are certain intransigencies in life. Okay, so we know it’s unfashionable to wear a Klan hood, but look at how these anonymous message boards are operating. That’s not so far from the spirit of planned rallies, trying to terrorize people anonymously. Look at the issue of black criminality. That hasn’t changed. It’s just been modified in different ways. Look at the issue of mental health. That actually has changed because of the national outcry — we’re all trying to figure this out, but the things that are getting people to say they need help haven’t changed. You and I both know there have been radical positive changes and opportunities. Neither of us would have been there at Yale fifty years ago. That doesn’t mean we can be satisfied, and that doesn’t mean that people aren’t going to have really difficult challenges along the way.

There have been people who look at this situation and say, “These students, who are at one of the most élite institutions in the United States and are reacting in this way, they are coddled and thin-skinned and they should just maybe toughen up. That’s the biggest thing they need to do.”

I understand that. This is not just a black problem or a brown problem or a women’s problem or whatever. We are seeing a generation of students, and I don’t know why, who do seem less resilient than in the past. I think part of it is that things aren’t mediated like they have been in the past. You don’t have the luxury of sitting down and pondering what somebody just said, because you’re too busy putting it into a Tweet and saying, “This is an outrage.” There’s no mediation of ideas. It’s all off the top of my head and it’s pain, in this case.

I think that, because people are not getting enough sleep, and these things just keep on, Tweets keep coming in, that they are not equipped properly to process it all. I think that’s a major part of it. The other part is that students have been struggling at Yale for a long time, and at similar institutions. The administrations were not set up even to care about them. It’s not just that maybe students are less resilient, it’s that the administrations actually are doing more work to identify people who are struggling. In a different era, if you had a drinking problem, there’s a nod and a wink, and that’s just the way Buster behaved. Now we understand the women’s side, that this thing is a real problem, and, hey, wait a second, this guy drinks and he sexually assaults somebody.

We’ve got to deal with that. You build up an apparatus to deal with people in crisis, and it actually helps us understand that — you know what? — more people are in crisis than we actually thought. I think these things go hand in hand, and I don’t think anybody’s really figured it out. We can claim we figured it out, but I think no one’s got the patent on that one yet.

I think I’ve said it, but I’ve actually been buoyed in the last couple days, because I’ve seen the Yale that I believe is normal — a really smart school confronting a problem and trying in a creative way to solve it together. That sounds like an advertisement but I actually believe that it operates that way. People are being increasingly willing to presume good faith on someone else’s behalf instead of just being negative. It’s as simple as that. Time will tell where this all shakes out, but I am cautiously optimistic that we are moving to a different place here. Hell, I’ve been wrong three or four times already this week, so who knows?

The New Intolerance of Student Activism

A fight over Halloween costumes at Yale has devolved into an effort to censor dissenting views.

The Atlantic

November 9, 2015

Professor Nicholas Christakis lives at Yale, where he presides over one of its undergraduate colleges. His wife Erika, a lecturer in early-childhood education, shares that duty. They reside among students and are responsible for shaping residential life. And before Halloween, some students complained to them that Yale administrators were offering heavy-handed advice on what Halloween costumes to avoid.

Erika Christakis reflected on the frustrations of the students, drew on her scholarship and career experience, and composed an email inviting the community to think about the controversy through an intellectual lens that few if any had considered. Her message was a model of relevant, thoughtful, civil engagement.

For her trouble, a faction of students are now trying to get the couple removed from their residential positions, which is to say, censured and ousted from their home on campus. Hundreds of Yale students are attacking them, some with hateful insults, shouted epithets, and a campaign of public shaming. In doing so, they have shown an illiberal streak that flows from flaws in their well-intentioned ideology.

Those who purport to speak for marginalized students at elite colleges sometimes expose serious shortcomings in the way that their black, brown, or Asian classmates are treated, and would expose flaws in the way that religious students and ideological conservatives are treated too if they cared to speak up for those groups. I’ve known many Californians who found it hard to adjust to life in the Ivy League, where a faction of highly privileged kids acculturated at elite prep schools still set the tone of a decidedly East Coast culture. All else being equal, outsiders who also feel like racial or ethnic “others” typically walk the roughest road of all.

That may well be true at Yale.

But none of that excuses the Yale activists who’ve bullied these particular faculty in recent days. They’re behaving more like Reddit parodies of “social-justice warriors” than coherent activists, and I suspect they will look back on their behavior with chagrin. The purpose of writing about their missteps now is not to condemn these students. Their young lives are tremendously impressive by any reasonable measure. They are unfortunate to live in an era in which the normal mistakes of youth are unusually visible. To keep the focus where it belongs I won’t be naming any of them here.

The focus belongs on the flawed ideas that they’ve absorbed.

Everyone invested in how the elites of tomorrow are being acculturated should understand, as best they can, how so many cognitively privileged, ordinarily kind, seemingly well-intentioned young people could lash out with such flagrant intolerance.

What happens at Yale does not stay there.

With world-altering research to support, graduates who assume positions of extraordinary power, and a $24.9 billion endowment to marshal for better or worse, Yale administrators face huge opportunity costs as they parcel out their days. Many hours must be spent looking after undergraduates, who experience problems as serious as clinical depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, and sexual assault. Administrators also help others, who struggle with financial stress or being the first in their families to attend college.

It is therefore remarkable that no fewer than 13 administrators took scarce time to compose, circulate, and co-sign a letter advising adult students on how to dress for Halloween, a cause that misguided campus activists mistake for a social-justice priority.

“Parents who wonder why college tuition is so high and why it increases so much each year may be less than pleased to learn that their sons and daughters will have an opportunity to interact with more administrators and staffers — but not more professors,” Benjamin Ginsberg observed in Washington Monthly back in 2011. “For many of these career managers, promoting teaching and research is less important than expanding their own administrative domains.” All over America, dispensing Halloween costume advice is now an annual ritual performed by college administrators.

Erika Christakis was questioning that practice when she composed her email, adding nuance to a conversation that some students were already having. Traditionally, she began, Halloween is both a day of subversion for young people and a time when adults exert their control over their behavior: from bygone, overblown fears about candy spiked with poison or razorblades to a more recent aversion to the sugar in candy.

“This year, we seem afraid that college students are unable to decide how to dress themselves on Halloween,” she wrote. “I don’t wish to trivialize genuine concerns about cultural and personal representation, and other challenges to our lived experience in a plural community. I know that many decent people have proposed guidelines on Halloween costumes from a spirit of avoiding hurt and offense. I laud those goals, in theory, as most of us do. But in practice, I wonder if we should reflect more transparently, as a community, on the consequences of an institutional (bureaucratic and administrative) exercise of implied control over college students.”

It’s hard to imagine a more deferential way to begin voicing her alternative view. And having shown her interlocutors that she respects them and shares their ends, she explained her misgivings about the means of telling college kids what to wear on Halloween:

I wanted to share my thoughts with you from a totally different angle, as an educator concerned with the developmental stages of childhood and young adulthood.

As a former preschool teacher... it is hard for me to give credence to a claim that there is something objectionably “appropriative” about a blonde-haired child’s wanting to be Mulan for a day. Pretend play is the foundation of most cognitive tasks, and it seems to me that we want to be in the business of encouraging the exercise of imagination, not constraining it.

I suppose we could agree that there is a difference between fantasizing about an individual character vs. appropriating a culture, wholesale, the latter of which could be seen as (tacky)(offensive)(jejeune)(hurtful), take your pick. But, then, I wonder what is the statute of limitations on dreaming of dressing as Tiana the Frog Princess if you aren’t a black girl from New Orleans? Is it okay if you are eight, but not 18? I don’t know the answer to these questions; they seem unanswerable. Or at the least, they put us on slippery terrain that I, for one, prefer not to cross.

Which is my point.

I don’t, actually, trust myself to foist my Halloweenish standards and motives on others. I can’t defend them anymore than you could defend yours.

When I was in college, a position of this sort taken by a faculty member would likely have been regarded as a show of respect for all students and their ability to think for themselves. She added, “even if we could agree on how to avoid offense,” there may be something lost if administrators try to stamp out all offense-giving behavior:

I wonder, and I am not trying to be provocative: Is there no room anymore for a child or young person to be a little bit obnoxious... a little bit inappropriate or provocative or, yes, offensive? American universities were once a safe space not only for maturation but also for a certain regressive, or even transgressive, experience; increasingly, it seems, they have become places of censure and prohibition. And the censure and prohibition come from above, not from yourselves! Are we all okay with this transfer of power? Have we lost faith in young people's capacity — in your capacity — to exercise self-censure, through social norming, and also in your capacity to ignore or reject things that trouble you?

In her view, students would be better served if colleges showed more faith in their capacity to work things out themselves, which would help them to develop cognitive skills. Nicholas says: “if you don’t like a costume someone is wearing, look away, or tell them you are offended. Talk to each other. Free speech and the ability to tolerate offence are hallmarks of a free and open society,” she wrote. “But — again, speaking as a child development specialist — I think there might be something missing in our discourse about … free speech (including how we dress) on campus, and it is this: What does this debate about Halloween costumes say about our view of young adults, of their strength and judgment? In other words: Whose business is it to control the forms of costumes of young people? It's not mine, I know that.”

That’s the measured, thoughtful pre-Halloween email that caused Yale students to demand that Nicholas and Erika Christakis resign their roles at Silliman College. That’s how Nicholas Christakis came to stand in an emotionally charged crowd of Silliman students, where he attempted to respond to the fallout from the email his wife sent.

Watching footage of that meeting, a fundamental disagreement is revealed between professor and undergrads. Christakis believes that he has an obligation to listen to the views of the students, to reflect upon them, and to either respond that he is persuaded or to articulate why he has a different view. Put another way, he believes that one respects students by engaging them in earnest dialogue. But many of the students believe that his responsibility is to hear their demands for an apology and to issue it. They see anything short of a confession of wrongdoing as unacceptable. In their view, one respects students by validating their subjective feelings.

Notice that the student position allows no room for civil disagreement.

Given this set of assumptions, perhaps it is no surprise that the students behave like bullies even as they see themselves as victims. This is most vividly illustrated in a video clip that begins with one student saying, “Walk away, he doesn’t deserve to be listened to.”

At Yale, every residential college has a “master” — a professor who lives in residence with their family, and is responsible for its academic, intellectual, and social life. “Masters work with students to shape each residential college community,” Yale states, “bringing their own distinct social, cultural, and intellectual influences to the colleges.” The approach is far costlier than what’s on offer at commuter schools, but aims to create a richer intellectual environment where undergrads can learn from faculty and one another even outside the classroom.

“In your position as master,” one student says, “it is your job to create a place of comfort and home for the students who live in Silliman. You have not done that. By sending out that email, that goes against your position as master. Do you understand that?!”

“No,” he said, “I don’t agree with that.”

The student explodes, “Then why the fuck did you accept the position?! Who the fuck hired you?! You should step down! If that is what you think about being a master you should step down! It is not about creating an intellectual space! It is not! Do you understand that? It’s about creating a home here. You are not doing that!”

The Yale student appears to believe that creating an intellectual space and a home are at odds with one another. But the entire model of a residential college is premised on the notion that it’s worthwhile for students to reside in a campus home infused with intellectualism, even though creating it requires lavishing extraordinary resources on youngsters who are already among the world’s most advantaged. It is no accident that masters are drawn from the ranks of the faculty.

The student finally declares, “You should not sleep at night! You are disgusting!” Bear in mind that this is a student described by peers with phrases like, to cite one example, “I've never known her to be anything other than extremely kind, level-headed, and rational.” But her apparent embrace of an ideology that tends toward intolerance produces a very different set of behaviors.

In the face of hateful personal attacks like that, Nicholas Christakis listened and gave restrained, civil responses. He later magnanimously tweeted, “No one, especially no students exercising right to speech, should be judged just on the basis of a short video clip.” (He is right.) And he invited students who still disagreed with him, and with his wife, to continue the conversation at a brunch to be hosted in their campus home.

In “The Coddling of the American Mind,” Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt argued that too many college students engage in “catastrophizing,” which is to say, turning common events into nightmarish trials or claiming that easily bearable events are too awful to bear. After citing examples, they concluded, “smart people do, in fact, overreact to innocuous speech, make mountains out of molehills, and seek punishment for anyone whose words make anyone else feel uncomfortable.”

What Yale students did next vividly illustrates that phenomenon.

According to The Washington Post, “several students in Silliman said they cannot bear to live in the college anymore.” These are young people who live in safe, heated buildings with two Steinway grand pianos, an indoor basketball court, a courtyard with hammocks and picnic tables, a computer lab, a dance studio, a gym, a movie theater, a film-editing lab, billiard tables, an art gallery, and four music-practice rooms. But they can’t bear this setting that millions of people would risk their lives to inhabit because one woman wrote an email that hurt their feelings?

Another Silliman resident declared in a campus publication, “I have had to watch my friends defend their right to this institution. This email and the subsequent reaction to it have interrupted their lives. I have friends who are not going to class, who are not doing their homework, who are losing sleep, who are skipping meals, and who are having breakdowns.” One feels for these students. But if an email about Halloween costumes has them skipping class and suffering breakdowns, either they need help from mental-health professionals or they’ve been grievously ill-served by debilitating ideological notions they’ve acquired about what ought to cause them pain.

The student next described what she thinks residential life at Yale should be. Her words: “I don’t want to debate. I want to talk about my pain.” In fact, students were perfectly free to talk about their pain. Some felt entitled to something more, and that is what prolonged the debate — not a faculty member who’d rather have been anywhere else.

As students saw it, their pain ought to have been the decisive factor in determining the acceptability of the Halloween email. They thought their request for an apology ought to have been sufficient to secure one. Who taught them that it is righteous to pillory faculty for failing to validate their feelings, as if disagreement is tantamount to disrespect? Their mindset is anti-diversity, anti-pluralism, and anti-tolerance, a seeming data-point in favor of April Kelly-Woessner’s provocative argument that “young people today are less politically tolerant than their parents’ generation.”

Hundreds of Yale students have now signed an open letter to Erika Christakis that is alarming in its own right, not least because it is so poorly reasoned. “Your email equates old traditions of using harmful stereotypes and tropes to further degrade marginalized people, to preschoolers playing make believe,” the letter inaccurately summarizes. “This both trivializes the harm done by these tropes and infantilizes the student body to which the request was made.” Up is down. The person saying that adult men and women should work Halloween out among themselves is accused of infantilizing them. “You fail to distinguish the difference between cosplaying fictional characters and misrepresenting actual groups of people,” the letter continues, though Erika Christakis specifically wrote in her Halloween email, “I suppose we could agree that there is a difference between fantasizing about an individual character vs. appropriating a culture, wholesale, the latter of which could be seen as (tacky)(offensive)(jejeune)(hurtful), take your pick.”

Hundreds of Yalies signed on to the blatant misrepresentations of her text. The open letter continues:

In your email, you ask students to “look away” if costumes are offensive, as if the degradation of our cultures and people, and the violence that grows out of it, is something that we can ignore. We were told to meet the offensive parties head on, without suggesting any modes or means to facilitate these discussions to promote understanding.

This beggars belief. Yale students told to talk to each other if they find a peer’s costume offensive helplessly declare that they’re unable to do so without an authority figure specifying “any modes or means to facilitate these discussions,” as if they’re Martians unfamiliar with a concept as rudimentary as disagreeing in conversation, even as they publish an open letter that is, itself, a mode of facilitating discussion.

“We are not asking to be coddled,” the open letter insists. “The real coddling is telling the privileged majority on campus that they do not have to engage with the brutal pasts that are a part of the costumes they seek to wear.” But no one asserted that students should not be questioned about offensive costumes — only that fellow Yale students, not meddling administrators, should do the questioning, conduct the conversations, and shape the norms for themselves. “We simply ask that our existences not be invalidated on campus,” the letter says, catastrophizing.

This notion that one’s existence can be invalidated by a fellow 18-year-old donning an offensive costume is perhaps the most disempowering notion aired at Yale.

It ought to be disputed rather than indulged for the sake of these students, who need someone to teach them how empowered they are by virtue of their mere enrollment; that no one is capable of invalidating their existence, full stop; that their worth is inherent, not contingent; that everyone is offended by things around them; that they are capable of tremendous resilience; and that most possess it now despite the disempowering ideology foisted on them by well-intentioned, wrongheaded ideologues encouraging them to imagine that they are not privileged.

Here’s one of the ways that white men at Yale are most privileged of all: When a white male student at an elite college says that he feels disempowered, the first impulse of the campus left is to show him the extent of his power and privilege. When any other students say they feel disempowered, the campus left’s impulse is to validate their statements. This does a huge disservice to everyone except white male students. It’s baffling that so few campus activists seem to realize this drawback of emphasizing victim status even if college administrators sometimes treat it as currency.

That isn’t to dismiss all complaints by Yale students. If contested claims that black students were turned away from a party due to their skin color are true, for example, that is outrageous. If any discrete group of students is ever discriminated against, or disproportionately victimized by campus crime, or graded more harshly by professors, then of course students should protest and remedies should be implemented.

Some Yalies are defending their broken activist culture by seizing on more defensible reasons for being upset. “The protests are not really about Halloween costumes or a frat party,” Yale senior Aaron Lewis writes. “They’re about a mismatch between the Yale we find in admissions brochures and the Yale we experience every day. They’re about real experiences with racism on this campus that have gone unacknowledged for far too long. The university sells itself as a welcoming and inclusive place for people of all backgrounds. Unfortunately, it often isn’t.”

But regardless of other controversies at Yale, its students owe Nicholas and Erika Christakis an apology. And they owe apologies to other objects of their intolerance, too.

The most recent incident occurred over the weekend. During a conference on freedom of speech, Greg Lukianoff reportedly said, “Looking at the reaction to Erika Christakis’s email, you would have thought someone wiped out an entire Indian village.” An attendee posted that quote to Facebook. “The online Facebook post led a group of Native American women, other students of color, and their supporters to protest the conference in an impromptu gathering outside of LC 102, where the Buckley event was taking place,” the Yale Daily News reported.

A bit later the protesters disgraced themselves (emphasis added):

Around 5:45 p.m., as attendees began to leave the conference, students chanted the phrase “Genocide is not a joke” and held up written signs of the same words. Taking Howard’s reminder into account, protesters formed a clear path through which attendees could leave.

A large group of students eventually gathered outside of the building on High Street, where several attendees were spat on, according to Buckley fellows who were present during the conference. One Buckley Fellow added that he was spat on and called a racist. Another, who identifies as a minority himself, said he has been labeled a “traitor” by several.

These students were offended by one person’s words, and were free to offer their own words in turn. That wasn’t enough for them, so they spat on different people who listened to those words and called one minority student a traitor to his race. In their muddled ideology, the Yale activists had to destroy the safe space to save it.

What I Learned This Semester at Yale

Students of color are not separatists practicing identity politics — they are fed up with false histories and a false present.

by Daniel Judt, a junior at Yale majoring in American History

Published in The Nation, December, 2015

On July 1, I received an e-mail from a fellow Yale student. She urged me to sign a petition to change the name of Calhoun College, a Yale residential building named after John C. Calhoun, the South Carolina statesman who graduated from Yale in 1804. The e-mail called Calhoun “the U.S.’s most ardent supporter of slavery.” I clicked on the petition, which began: “It is deeply upsetting that it has taken a tragedy such as the shooting in Charleston to initiate the removal of symbols of white supremacy from public spaces.”

Just weeks before, Dylann Roof shot nine people at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church because they were black. This is the kind of racism white America knows how to deal with. It is the racism I learned about in high school. Klan racism, Bull Connor racism. “You are raping our women,” Roof had said before he sprayed the church with blood. Roof wanted his actions to launch a race war. In photos on his website, he posed proudly with a Confederate flag.

Like most people, I was livid about Charleston. I wanted to strip the Confederate flag from every statehouse, every town square, every lawn. But on Calhoun, I froze. A Confederate flag was easy. Calhoun seemed more complicated. I abhorred the man and his ideas, of course. But maybe his name on a building was a good way to remember that? Should Yale forget John C. Calhoun? I imagined a student asking, four or five years down the road, “Calhoun who?” I didn’t sign the petition.

Conversations about race at Yale boiled over on November 5. Students confronted Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway in the middle of the campus and, for the better part of three hours, tried to explain why they were hurt and angry. I wasn’t at Yale when this happened. I was in Atlanta, doing research for a paper on the Atlanta Cyclorama, a painting that many have interpreted as a commemoration of the Confederacy. When I received texts from my friends telling me what was going on at Yale, I was in an archive reading an article about the premiere of Gone With the Wind back in 1939.

Mayor William Hartsfield declared the day of the premiere a holiday in Atlanta. The city was festive and frenzied. Atlanta’s own Margaret Mitchell had written a book about Atlanta’s own battle, and just three years later Hollywood — Clark Gable! — had made Atlanta’s own film. In the days leading up to the premiere, the city rewound some 70 years. The Loew’s Grand Theatre had been specially renovated, its façade transformed into a Southern mansion. Newspapers ran thick souvenir editions with detailed instructions for the rebel yell. Young men and young women asked their grandparents if they could borrow clothes. The hoop skirt returned. The gray uniform was passed down. Oh, and did they still have their swords?

That night, 18,000 Atlantans lined an avenue to watch their past parade by. The past came in a shiny black car. Hattie McDaniel, whose performance the Atlanta Constitution adored, was not in the car and was not at the theater. Blacks were not allowed in the Loew’s Grand. Margaret Mitchell was in the car, and she was very pleased. “I feel it has been a great thing for Georgia and the South to see the Confederates come back,” she said, beaming.

I couldn’t figure out if she was talking about the film.

Jeff Hobbs’s The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace is about the experience of one black student, Robert Peace, at Yale from 1998 to 2002. Peace grew up with his mother in a violent neighborhood just outside Newark, and his father was imprisoned when he was 7 — but he made it to Yale. Despite excelling academically and socially, he never felt truly comfortable or at home. Hobbs, Peace’s white roommate, says this of their relationship: “He knew I could never understand, and he was kind enough not to hold my sheltered obliviousness against me ... He would share with me the smallest fragment of his world and then step back into the whole of mine.”

I cling to my sheltered obliviousness every Saturday morning, and the inmates at Manson Youth Correctional Facility are kind enough not to hold it against me. I go there to tutor. Manson has grey concrete walls, a single story high, that seem to go on forever — out of sight from the parking lot, at least. The visitor entrance is a single gray door with a single glass pane at eye level. Inside is a visitor’s desk that is itself another cement wall with another single glass pane, this one at chest height. Behind that pane sits a woman who makes us sign a sheet and hand over our Yale IDs.

The group of prisoners I work with is post-GED, 18–21 years old. They told us they wanted to learn about political issues. About race, one of them said. The six inmates in my tutoring program do not buy the idea of cultural appropriation. Four are black, two Latino. When I suggested it would be wrong if I wore blackface for Halloween, they suggested I was full of shit. “You do whatever you want, and if I think you’re doing it for the wrong reasons, I’ll let you know,” Mac said. I told them they should be angrier. They should be offended. They shrugged.

I had not bothered to ask them where they were from. What they saw, who they were. How they got here. I’m actually not allowed to ask them that last one — prison rules. They are quite literally forbidden from conveying their experiences to me. They are only allowed to shrug. After two hours, I left. I can always leave.

Student movements at Yale and other schools across the country are decrying the imbalance Hobbs describes. White students like myself are rarely aware of our own consciousness — and our own culture — when we enter into an intellectual discussion. When we speak from our experience, we do not have to recognize the consciousnesses of students of color. Those students of color, though, have to recognize both their own consciousness and those of their white peers.

These student movements are political movements. They are battle cries of a mobilized generation. Yet instead of dealing with the political issues that they raise, critics on the right (and some on the left) have psychologized these movements, painting their leaders as whining children. They say that student protesters are acting from individual feelings, using muddled thinking, shouting down neutral civil discourse, and concerned with neither ideas nor politics. Or, that students are concerned with politics, but with the wrong, dangerous kind — egocentric and driven by identity.

But students of color are not separatists practicing identity politics. Their kind of politics does not exclude allies or abandon universal ethics. The demand is simply that we allow students of color to share more than just a fragment of their world.

Margaret Mitchell’s confederates are not back. Exclusion now comes in subtler forms, like the gray walls of a youth correctional facility. But there is a link between grandsons of confederates dressing up in their granddaddy’s uniforms and Yalies donning blackface for Halloween. Or between the Confederate flag at the South Carolina statehouse and John C. Calhoun’s name on a college dorm room. Students of color recognize this link. They are demanding that white students — white people — see it too.

Otherwise, American society will not work anymore. Students of color are not imagining hurt. They are not creating false history. They are not exaggerating pain. They want white people to understand how reflexively resistant we are to surrendering our American narrative. It is a narrative that disconnects us from our past and obscures our present. It lets us honor slaveholders and supremacists, glamorize emancipation — and dismiss angry, passionate, visceral voices of dissent as childish drivel. We ought to want no part of it.

Student activists are fed up with false histories and a false present. They are proposing we write a new American narrative, one that includes them. They want to inject their experiences into the body of civil discourse. A body whose blood, right now, runs white.

Yesterday, I signed that petition to rename Calhoun College.

Listening, learning, leading: Salovey and Holloway speak to alumni delegates

During the 2015 AYA Assembly, President Peter Salovey and Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway told alumni delegates that free speech and diversity should not be in conflict at the university.

The issues of race, diversity, free speech, and inclusion can make for complicated and often difficult conversations. Yale President Peter Salovey told nearly 500 Yale alumni leaders on Nov. 20 that he is ready to have those conversations on a national level and he is ready to have Yale take a lead on these powerful issues underlying a movement taking place across the nation, at Yale and other college campuses.

“Why not lead that conversation in a way that’s respectful, thoughtful, and that reflects how a university should lead,” said Salovey, who spoke along with Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway at the annual assembly of the Yale alumni. “This is an important opportunity, and I think we should seize it.”

Part of establishing that leadership position, the President and Dean noted, was taking the time to listen to all students and faculty as students organized rallies, a march for resilience, and a teach-in to address issues of race on campus. Holloway said the situation on campus was fluid, and he and Salovey thought it was important to listen and learn before announcing what steps would be taken.

While reaffirming support for Yale students, Salovey also reaffirmed his defense of free speech by citing the 1974 Woodward Report on Free Expression, which outlines Yale’s bedrock policy that expression of all kinds is tolerated at Yale, and there is no exception for controversial issues. Salovey stressed that free speech at Yale is not in jeopardy, and that free speech and diversity should not be issues in conflict.

“Expression of all kind is tolerated on this campus even when it offends us, even when it disgusts us, even when we disagree with it strongly,” he said. “The way to deal with such speech that offends us is with our speech. All should be allowed to listen to the views of others.”

The pair recounted the difficult, but necessary conversations they both had in the past weeks with students, faculty, and alumni about these issues at Yale.

“It was a thing of beauty,” Holloway said as he described the teach-in attended by hundreds of undergraduates, graduate and professional students, faculty, and staff. “They marched to say, ‘This is our Yale also. We belong also.’ It was a civil, peaceful articulation that Yale was capacious enough to handle all of our views. That’s Yale at its finest.”

Salovey and Holloway joined the students at the teach-in, and the leaders and students spent three hours educating one another. “We heard students talk about ways to look forward,” Holloway said. “This was not a moment about not getting into a party or a controversial email. It was about something deeper and more vital.” Students across the country are expressing frustration and speaking about not belonging at their respective institutions. We all need to listen.”

Salovey said that that there is a very real sense among underrepresented students that they experience acts toward them that are discriminatory and hurtful. “I think it happens in the world, and it happens on campuses,” he said. “I think it’s very real, and I think we should try to grapple with it. Students are not unrealistic about it. They simply say, ‘We just want to get the same kind of education that everybody else does. We feel like we don’t belong.’ These are members of our community simply saying, ‘We don’t want to be excluded. We want to be part of things.’”

“I view this not as something we should be running from or spinning, but rather as an opportunity for Yale to show the kind of leadership that we show on all issues,” the President added. “We should be in front of this national conversation and in creating campuses where everyone who comes feels like they belong, gets a great education, and has an enriching social experience regardless of their background before coming to Yale.”

Holloway spoke from his perspectives as an administrator, as a historian who studied civil rights and is currently teaching a lecture course on post-emancipation African-American history, and as a black man who had experienced some of the same things when he was an undergraduate.

“I knew intellectually the kinds of slights [the students have] endured were familiar to me when I was in college,” he said. “Things have gotten radically better, but the fact is that at an interpersonal level, it is still quite difficult to be a person from a marginalized community. I know for a fact that those of you who were in the first class of women at Yale know exactly what I’m talking about. You had to navigate a lot of things that the men did not have to navigate.”

Holloway also said that as privileged as he is to be the first black dean of Yale College, having privilege and resources doesn’t mean anything when you step into certain situations. “Part of me has to wonder if I’m pulled over what might happen. That is the reality of my life. I don’t say it to complain, but people need to understand that the undergraduate experience in its own way reflects that kind of reality. It’s historical: it’s not new, but it’s personal and it’s real. That’s what we’ve been hearing over these last few weeks.”

Holloway expressed pride in the steps the university announced it would take in a series of messages to the community. Salovey reaffirmed that the Christakises would continue as master and associate master of Silliman College, and also announced a variety of actions that Yale can put into motion immediately. Those actions reflect input from student groups, faculty groups, alumni, and parents. He noted that a center for the academic study of race and ethnicities had been discussed since 2009. Others are newer ideas that Salovey thinks are appropriate at this moment.

Before taking questions from the audience on everything from naming the new residential colleges to renaming Calhoun College, Salovey encouraged the alumni to engage on the issues of belonging and inclusion.

“Yale deserves your participation in this conversation,” he said.

Statement from President Salovey: Toward a better Yale

November 17, 2015

President Peter Salovey sent the following message to the Yale community on November 17.

In my 35 years on this campus, I have never been as simultaneously moved, challenged, and encouraged by our community — and all the promise it embodies — as in the past two weeks. You have given strong voice to the need for us to work toward a better, more diverse, and more inclusive Yale. You have offered me the opportunity to listen to and learn from you — students, faculty, staff, and alumni, from every part of the university.

I have heard the expressions of those who do not feel fully included at Yale, many of whom have described experiences of isolation, and even of hostility, during their time here. It is clear that we need to make significant changes so that all members of our community truly feel welcome and can participate equally in the activities of the university, and to reaffirm and reinforce our commitment to a campus where hatred and discrimination are never tolerated.

We begin this work by laying to rest the claim that it conflicts with our commitment to free speech, which is unshakeable. The very purpose of our gathering together into a university community is to engage in teaching, learning, and research — to study and think together, sometimes to argue with and challenge one another, even at the risk of discord, but always to take care to preserve our ability to learn from one another.

Yale’s long history, even in these past two weeks, has shown a steadfast devotion to full freedom of expression. No one has been silenced or punished for speaking their minds, nor will they be. This freedom, which is the bedrock of education, equips us with the fullness of mind to pursue our shared goal of creating a more inclusive community.

Four key areas, outlined below, will give structure to our efforts to build a more inclusive Yale, and the deans of all of Yale’s schools will provide leadership across the university. I look forward to working with everyone in the days and months ahead to refine and expand on these themes. In a time when universities and communities around the country are coming together to address longstanding inequalities, I believe that Yale can and should lead the way. Many of you have proposed ideas for constructive steps forward, and my hope is that our collective endeavors can become a model for others to emulate.

The conversations we are having today, about freedom of expression and the need for inclusivity and respect — principles that are not mutually exclusive — resonate deeply with the issue Dean Holloway and I addressed at the beginning of the semester, about the name of Calhoun College. At that time, I quoted President Lincoln and said that Yale, like our nation, has “unfinished work.” This is just as true with the work that stands before us now. I am eager to embark on it with you.

Strengthening the academic enterprise

Race, ethnicity, and other aspects of social identity are central issues of our era, issues that should be a focus of particularly intense study at a great university. For some time, Yale has been exploring the possibility of creating a prominent university center supporting the exciting scholarship represented by these and related areas. Recent events across the country have made clear that now is the time to develop such a transformative, multidisciplinary center drawing on expertise from across Yale’s schools; it will be launched this year and will have significant resources for both programming and staff. Over time, this center will position Yale to stand at the forefront of research and teaching in these intellectually ambitious and important fields.

Yale already has outstanding faculty members who are doing cutting-edge scholarship on the histories, lives, and cultures of unrepresented and under-represented communities. To build on this strong foundation, I will ask the committee that oversees the allocation of resources in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences to devote four additional faculty positions to these areas, housing them in relevant FAS departments and programs. We will hire the very best scholars to bring their knowledge and insight to our students and the broader community.

In the meantime, in expectation of increased student interest, we are adding additional teaching staff and courses in Yale College starting in spring 2016 that address these topics. To continue the conversation outside the classroom, throughout the university, Yale will launch a five-year series of conferences on issues of race, gender, inequality, and inclusion.

Earlier this month Provost Ben Polak and I announced a $50 million, five-year, university-wide initiative that will enable all of our schools to enhance faculty diversity. This is a campus-wide priority. Within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, which includes the faculty who teach in Yale College, we will invite one of our senior faculty members to take on the responsibility of helping to guide the FAS in its diversity efforts and its implementation of the initiative. This new leadership position will be located in the office of the dean of the FAS, and will hold the title of deputy dean for diversity in the FAS and special advisor to the provost and president. The deputy dean will also coordinate support and mentoring for our untenured faculty. Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Tamar Gendler and the FAS deputy dean will convene a new committee to advise them about faculty diversity issues and strategies for inclusion.

Expanding programs, services, and support for students

Starting in 2016-2017, the program budgets for the four cultural centers will double, augmenting the increases made this year and the ongoing facilities upgrades resulting from last year’s external review. The expanded funding will enable the centers to strengthen support for undergraduate students and extend support to the graduate and professional student communities. Staffing will be adjusted, and facilities for each center will continue to be assessed with an eye toward identifying additional enhancements. In addition, I will ask the deans of our schools to explore ways in which our community, including our extraordinary alumni, can increase the support and mentorship they provide to our students.

Financial aid policies for low-income students in Yale College, the subject of a spring 2015 report by the Yale College Council, will also see improvements beginning in the next academic year. Details will soon be announced, and will include a reduction in the student effort expectation for current students. In the meantime, funds for emergencies and special circumstances already available through the residential colleges, and the financial aid offices are also being reviewed and increased. We will follow up with the graduate and professional schools to ensure that they also have the capacity to support students in times of emergency.

Professional counselors from Yale Health will work with the directors of the four cultural centers to schedule specified hours at each center, building on the existing mental health fellows program in the residential colleges. Additional multicultural training will be provided to all of the staff in the Department of Mental Health and Counseling at Yale Health, and renewed efforts will be made to increase the diversity of its professional staff. These changes are in addition to the improvements that we are already making in our mental health services for students across the university.

Improving institutional structures and practices

Educating our community about race, ethnicity, diversity, and inclusion begins with the university’s leadership. I, along with the vice presidents, deans, provosts, and other members of the administration, will receive training on recognizing and combating racism and other forms of discrimination in the academy. Similar programs will be provided to department chairs, directors of graduate and undergraduate studies, masters and deans, student affairs staff, and others across the university.

We are also making funds available to improve existing programs and develop new ones — both during orientation periods and beyond — that explore diversity and inclusion and provide tools for open conversations in all parts of the university about these issues. Programs may take the form of trainings, speaker series, or other ongoing activities. We will appoint a committee of students, faculty, and staff to help us develop and implement these efforts, so that we can learn to work together better to create an inclusive community, a community in which all feel they belong.

The work of creating robust and clear mechanisms for reporting, tracking, and addressing actions that may violate the university’s clear nondiscrimination policies will be rolled out in two phases: in the first, which will take place immediately, we will work with students to communicate more clearly the available pathways and resources for reporting and/or resolution. Then, in the spring, we will review and adopt, with input from students, measures to strengthen mechanisms that address discrimination. I have asked Secretary and Vice President for Student Life Kim Goff-Crews to lead this work.

Representations of diversity on campus

To broaden the visible representations of our community on campus, I am asking the Committee on Public Art to hold an open session at which members of the campus can present ideas for how we might better convey and celebrate our diversity and its history. Just as Yale in recent years has heralded the role and contributions of women by increasing the number of portraits of women across campus and by commissioning the Women’s Table in front of Sterling Memorial Library, we can more accurately reflect the vibrancy of our university community.

Finally, many of you have asked with renewed interest about the names of the new residential colleges as well as the name of Calhoun College. In the next year, the Yale Corporation will be deciding the names of the two new colleges that will open in August 2017. I have asked the Corporation’s senior fellow to organize meetings with several other fellows at which community members can express their views both about names for the new colleges and about Calhoun. Corporation fellows value, and will continue to hold, in-person and other discussions as they move toward making decisions.

We take these important steps in the full knowledge that our community will have to do much more to create a fully inclusive campus. To lead the way forward, I am creating a presidential task force representing all constituencies to consider other projects and policies. The efforts that we launch today, and the commitment to the core values they represent, must be continuous, ongoing, and shared by all of us. I thank all of you for the perspectives you have offered already and for all that you will contribute to the work that lies ahead.

Columns by Cole Aronson, Yale Daily News

The following content includes 5 columns by Cole Aronson, a sophomore in Calhoun College who writes a weekly column as a staff columnist for the Yale Daily News.

- Defending Erika Christakis

- Replace wounds with discourse

- The "next" worse Yale

- Fight for the Yale we love

- What should Yalies know?

Defending Erika Christakis

by Cole Aronson, staff columnist, Yale Daily News

November 2, 2015

On Wednesday, Dean Burgwell Howard wrote an email to Yalies asking them not to “threaten [Yale’s] sense of community” with their Halloween costume choices. “We would hope,” Howard writes, “that people would actively avoid those circumstances that … disrespect, alienate, or ridicule … based on race, nationality, or population.” And then, on Friday, Erika Christakis, associate master of Silliman College, wrote to the Silliman community about the dangers of making campuses “places of censure and prohibition.”

Christakis laments that emails like Howard’s suggest that adults have “lost faith in young people’s capacity … to exercise self-censure, through social norming.” This “shift from individual to institutional agency” disempowers students. If Yalies want their culture changed, Christakis argues, edicts from above are the wrong way to do it.

To be sure, the University administration can and should counter egregious student behavior. Yale is not just a disburser of facts, but an institution to make moral men and women. At the same time, an email concerning students’ Halloween attire seems a bit petty, especially given the binge drinking and debauchery abounding the same evening.

Ultimately, though, Christakis thinks the administration — and everyone else — lacks a way to distinguish among “appropriative” costumes and more benign ones. “What is the statute of limitations,” she wonders, “on … dressing up as Tiana the Frog Princess if you aren’t a black girl from New Orleans?” Though there’s certainly a difference between dressing as Tiana and wearing blackface, this reply misses the point: Howard and Christakis’s critics on social media are not treating students who dress up in supposedly “appropriative” costumes in good faith.

Howard concedes in his email that “in many cases the student wearing the costume has not intended to offend.” However, “their actions or lack of forethought have sent a far greater message than any apology could after the fact.” Burgwell dissociates the costume from the person wearing it. What makes a given action different from person to person is the intention behind it — for instance, it’s okay for parents to yell at their children in public. If a stranger did the same, we’d consider it boorish. So why would we remonstrate someone who in daily life is racially tolerant, liberal, etc. because they wore a borderline insensitive costume?

Burgwell simply assumes that minority students will take offense at such garb. But they might be less perturbed if they considered that the aim of students wearing costumes on Halloween is — almost certainly — to have fun, not reinstitute Jim Crow or kick minority students out of Yale. They might, of course, find some costumes to be in poor taste, as I do. In that case, they should do what Christakis urged and explain their feeling to their peers in a constructive way.

Yet an open letter to Christakis recently circulated among the student body takes Burgwell’s uncharitability one step further. Already signed by hundreds of Yalies, it accuses Christakis of asking minority students to invite “ridicule and violence onto [them]selves” by allowing peers to wear potentially offensive costumes. Christakis, the letter says, wants folks to ignore the “violence” that grows out of the “degradation of … cultures and people.”

The philosopher Slavoj Zizek could not have overstated it better. Christakis was simply arguing that a university should not trouble itself with the tasteless outfits of a few students, even if those students are criticized for being obnoxious. The letter makes the unbelievably serious claim that Christakis is promoting physical harm against minority students. Such a response hardly dignifies a response.

Another point Christakis makes is that we do not care about all instances of offense. “No one around campus,” she writes, “seems overly concerned about the offense taken by religiously conservative folks to skin-revealing costumes.” Definitely, Yale ought to worry more about white students’ prejudice toward black students than the reverse. But do we want a campus where folks who belong to certain groups have their sensibilities ignored and those who belong to other groups are entitled to censor speech? Religious conservatives aren’t out policing the denizens of Toad’s, even though many surely think that they ought to dress modestly. And they certainly aren’t accusing scantily clad or axe-wielding trick-or-treaters of promoting “violence” against anyone.

The Christakis donnybrook is a lesson in intellectual charity and treating all students as adults. Christakis is not hostile to any minorities. To the contrary, by advocating a campus where feather-dress costumes are met not with tar, but with dialogue, Christakis treats all students as equals. Her opponents ought to emulate her.

Replace wounds with discourse

by Cole Aronson, staff columnist, Yale Daily News

November 9, 2015

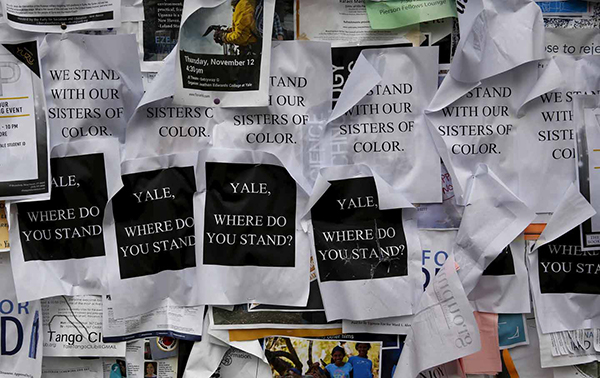

Yale had a rough week. A woman reported two Fridays ago that the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity hosted a “white girls only” party. Hundreds of students confronted Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway and Silliman College Master Nicholas Christakis last Thursday about race at Yale. And dozens protested outside the William F. Buckley Program’s conference on free speech this weekend. Hundreds of students of color and their allies exhorted Yale to improve. Yale should heed (much of) their message while deploring (some of) their methods.

Many students on Cross Campus expressed anger about the alleged — since Yale is investigating, I won’t speculate on the truth of the claim — “white girls only” party and the treatment of minority students generally. A discussion about racism at Yale should include an acknowledgment that a university with so many students feeling so much pain is failing somehow. That said, the reaction to the alleged party is evidence that Yale has already developed some checks on flagrant bigotry. Hours after the initial allegation, hundreds took to social media to sympathize with the alleged victim, SAE’s president was in contact with the Yale administration and, days later, hundreds convened on Cross Campus in solidarity with Yale’s women of color.

While such blatant bigotry is heavily publicized when it occurs, subtler forms of discrimination appear to be much more common. Conservatives especially should admit this. Institutions and people develop behaviors over centuries. It’s not credible to suggest that racism will disappear from Yale’s community just because it’s now populated by liberal Democrats. The difficult question is what counts as racism.

One view of this question was aired to Holloway last Thursday. Students grieved about unsolved mental-health problems, the lack of minority faculty in certain departments, and callous freshman roommates. I was not in Silliman College later that day but I understand that similar things were said to Master Christakis, along with complaints about the email his wife, professor Erika Christakis, sent the Silliman community two weeks ago. The view of many students was, in effect, that the important thing about an action is how it is received, not the intention behind it.

This view’s main problem is its lack of charity. By divorcing action from actor, it gives a general warrant for people to judge what others say and mean on completely arbitrary and expansive grounds. Was Christakis authorizing students to wear offensive costumes, or making minority students unsafe? Or was she expressing that perhaps certain costumes are, even if in poor taste, meant in jest, rather than in harm? A plain reading of her email yields the latter interpretation. And we consider people’s intentions all the time in everyday life. When someone asks, “How was your day?,” one doesn’t think, “She wants to subject me to miserable reminiscences of the six things that went wrong before lunch.” One thinks, “She cares how I’m doing .”

The lack of charity inherent in judging actions independent of intentions is already having consequences. Many students behaved reprehensibly toward Holloway and Christakis, though neither man means students harm. We cannot have a university if students say, “What the f—k have you been doing?” and impute racial betrayal to the Yale College dean, or when a student commands a teacher to be quiet. Whatever conversation Yale has over the coming months, all Yalies should condemn this sort of abuse. And Yale administrators harm their students when it permits them to say such ugly things to authority figures without consequences. That’s simply not how adults behave.

I still think there is something to the view that racism is a matter of reception, rather than intent. Further, those who hold this view and are in pain now deserve acknowledgment. No good discussion can occur without their input. But people who hold that view cannot be permitted to shut down other people from expressing their views simply because they offend. Then, a debate becomes a shouting match, and justice becomes the advantage of those who feel the most strongly. If a difficult discussion leads to cursing and insults, then Yale has failed to instill its students with a respect for the pursuit of truth.

Yale has to proceed along two paths. Too many feel too much hurt. Many students’ wounds need binding. But a wound is not itself an argument. This doesn’t mean it isn’t important: it’s cruel and wrong to tell a suffering friend their feelings don’t matter. But Yale needs a vision for moving past ameliorating pain and toward developing a university based on inquiry and respect. That requires malice toward none, and charity for all.

The world is indeed watching Yale — to see whether it can elevate students past the plane of grief to the plane of discourse, which is the University’s plane par excellence.

The "next" worse Yale

by Cole Aronson, staff columnist, Yale Daily News

November 16, 2015

Last Thursday evening, 200 students with the moniker “Next Yale” presented Yale President Peter Salovey with a list of demands. He promised a response sometime this week. As the administration ponders how to respond, it’s a good time to think about the purpose of Yale as a university, and how Next Yale’s demands relate to that purpose.

We are here because, apart from our career aspirations, we find the pursuit of knowledge to be a worthwhile vocation. As Michael Oakshott, the British political thinker, said to his students at the London School of Economics in 1939, “‘Society,’ no doubt, will make demands upon you soon enough … [But] you have come here to get acquainted with truth and error, not with merely what is and what is not serviceable to a lunatic productivist society.”

The boundary between truth and error remains, at the very least, difficult to see.

Whether our knowledge is limited innately or simply as a function of inadequate technology, we do not know. Our knowledge of the limits of human knowledge remains itself limited. And so we will have to be content to live in a good amount of darkness.

The University, with its commitment to scholarship, to teaching, and to discourse, provides a place for those most committed to groping in that darkness. And though there may be occasional discoveries, both the most important answers and the questions most worth asking in the first instance remain fundamentally hidden. As a great teacher of political philosophy Leo Strauss wrote, “As long as there is no wisdom but only the quest for wisdom, the evidence of all solutions is necessarily smaller than the evidence of the problems.”

If this is true, then the proper attitude toward one’s opinions is a good deal of doubt. And therefore the proper attitude toward the marketplace of opinions is an open and tolerant one.

For as long as we think this, we should welcome disagreement. Not merely permit it in the public square, but seek it. We should, as Strauss writes, have the “boldness implied in the resolve to regard … the average opinions as extreme opinions which are at least as likely to be wrong as the most strange.”

Many have claimed that the debate at Yale is not fundamentally about “free speech.” Strictly speaking, they are correct. None of Next Yale’s demands would censor anyone. No speech would be disallowed that is currently permitted.

But the demands, if implemented, would narrow, not widen, our discourse. The demands also evince on the part of those making them an attitude hostile toward rigorous debate. Take the request for a “bias-reporting system.” For fear of formal reprimand, students and faculty would likely self-censor. While everyone should support a university culture that abhors outright bigotry — “white girls only” parties and the like — there’s a good deal of controversy about what qualifies as bigotry. Any “bias” guidelines given would probably be construed widely to encompass views without which any discussion would be impoverished. Imagine, for instance, that a professor argued that the breakdown of the black family has exacerbated poverty in the black community. Such a person might make the argument with total sympathy toward the black community. But, like former Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan when he made this very argument in 1965, such a person might be accused of bias or racism instead of presenting respectable arguments in good faith. Accusations and name-calling would replace evidence and logic as the way to win a debate.

Similarly, removing the Christakises from their positions in Silliman would send the message that challenging unpopular views is to be discouraged. Many have said their job is, to borrow a phrase, not about creating an intellectual space — it’s about creating a home here.

But a home, especially at a university, shouldn’t be sanitized from difficult conversations. Those calling for the Christakises’ removal are claiming the opposite. They are upset about or offended by — that is, they vehemently disagree with — what Erika Christakis wrote in her email. (Of course, if Christakis had expressed equally controversial views agreeing with theirs, we would be hearing nothing about the “role of the master,” but never mind.) The University should encourage such disagreement. Christakis is simply adding her views to the debate. Let others support or oppose her.

A university is a community of those who want to reason together toward knowledge. Subjugating this process to subjective definitions of “bias,” and emotions more generally, will necessarily vitiate it. In order to pursue truth all the way, all must sacrifice their intellectual and emotional “safety” — euphemisms for complacency. If in the next Yale fewer make the sacrifice — and, therefore, engage in the process — it will be a far worse Yale.

Fight for the Yale we love

by Cole Aronson, staff columnist, Yale Daily News

November 30, 2015

I think President Peter Salovey’s recent email announcing changes aimed at “a more inclusive Yale” has bought only a pause in unrest on campus.

Rewarding any behavior encourages more of it. The Next Yale movement protested and demanded, and the Yale administration gave lots of money to its causes and intellectual ground to its views.

The movement says racism is bad, as if that’s controversial. It claims on the basis of uncheckable “lived experiences” that racism not only exists at Yale — a reasonable assumption for any large institution — but is everywhere at Yale. The movement then pushes solutions that it, as the self-appointed arbiter of racism on campus, knows are necessary to correct the problem.

As others have written on these pages recently, it is difficult for many people with a sense that something is wrong with this movement to speak up. Being against those who are against racism — and who claim it pervades Yale’s culture — makes one, of course, a bedfellow of racists.

But agreeing, as everyone does, that racism is wrong is different from agreeing with the worldview and goals of those who now claim a monopoly on opposition to and knowledge about racism. And that worldview and those goals, if they become Yale’s, will harm our school.

This movement has lauded a student who screamed at a teacher that she wanted not an intellectual space, but a “home.” The movement has demanded that its subjectivist definition of racism be conditioned into students and faculty. Some of its members have cursed at students of color who disagree with its message. And the movement has asked that students be required to take classes — normally forums for rigorous debate — that it seems eerily sure will cure them of their troglodytic views.

Yale administrators have been able to avoid certain ill-advised changes to University policy because they have administrative power. But it does not matter how many times administrators tout Yale’s unshakeable commitment to free speech if debate at Yale becomes intolerant, uncivil, and emotional. Yale can remain technically tolerant and still lose the sort of discourse it ought to encourage.

Yale needs a campaign of administrators, faculty, and students against the aspects of the movement which, if it advances, will harm the University’s intellectual life. A few points need making:

First, the University’s mission of pursuing truth through debate means that “emotional and intellectual safety” are secondary concerns. The right of people to speak their minds and the charity afforded to arguments made in good faith are paramount. Further, using emotions instead of reason for argument is shoddy. This does not mean telling students who feel hurt to simply stop feeling hurt. It means that personal feelings ought not be permitted to prevent discussion of difficult issues. Students asking to be kept safe from discomforting ideas are making requests opposed, as such, to the University’s ideals.