Class News

Gerald Shea '64 on living with partial deafness

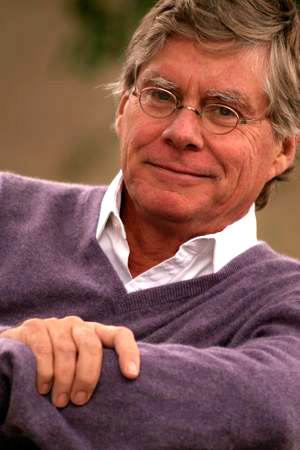

Gerry Shea became partially deaf at the age of 6 due to scarlet fever and chickenpox, though he didn't know it at the time and didn't discover it until the age of 34, almost by accident. His book Song Without Words chronicles his lifetime of coping with partial deafness, and was nominated in November 2013 for the National Book Critics Circle's best first book award (the John Leonard prize). You can buy the book here. Below are numerous articles and interviews with Gerry about the book, in chronological order (earliest first).

- Video interview

- Boston Globe review

- Poetry & Prose Bookstore interview (audio)

- CBC Radio interview (audio)

- Irish Times interview

- New Statesman review

- New York Journal of Books review

- Wall Street Journal article

- Open Source radio interview (audio)

- San Francisco/Sacramento book review

- Interview on the Mimi Geerges Show (video)

- Newstalk Dublin radio interview (audio)

- West Virginia Gazette review

- WCBN Ann Arbor interview

- Salem News Book Notes

- Book review, actiononhearingloss.uk

Book review, Boston Globe

Published February 22, 2013; re-published online December 2, 2014

The memoir genre has been often criticized as narcissistic navel-gazing, a wallowing in personal problems. Memoir writers, this critique goes, glorify their own behavior (however foolish) while blaming the rest of society for their problems. Enter Marblehead resident Gerald Shea, whose life story easily could have been a tale of self-pity. Instead, Shea’s Song Without Words constitutes everything that a great memoir can and should be.

Shea contracted scarlet fever as a boy, and as a result became profoundly (not completely) deaf. He wouldn’t be professionally diagnosed until age 34, thus compelling him to live a lot of his life, said one of his doctors later, as if he were running with a broken ankle. Shea simply carried on, working twice as hard to overcome his hearing loss. He would graduate Columbia Law School near the top of his class, then become a partner at a big Manhattan law firm, Debevoise & Plimpton. Shea describes what he needed to do to reach such heights with clarity and without complaint.

Song Without Words is both a work of literary art and a manual for understanding the difficult world Shea inhabits. Instead of complaining, Shea patiently portrays what it’s like to be unable to comprehend spoken language in real time, and how he brilliantly developed his own “transitional” language, which he calls “lyricals,” and then translates these lyricals back into English.

Shea describes the biggest challenge of his life: the lost time (in the Proustian sense, too) between what people say and what he understands. Sometimes, meaning is simply lost in translation. In his work as a high-powered commercial lawyer representing Fortune 500 companies in multi-billion-dollar deals, being unable at times to understand others became a massive professional obstacle. Shea succeeded, but the toll it took on him emotionally and physically, the lunches he spent in the bathroom sipping Mylanta from the bottle as his stomach churned with stress, was significant. Shea is impressive that, with so much to complain about, he complains so little.

Shea beautifully describes the language of the sounds he hears, letting us see how he races to translate them into meaning. At a meeting with the New York City Builders Association, for example, Shea hears another lawyer say “any fissing of the pride of lament would violate the antitrust law.” Shea translates: “lament” becomes “cement”; “fissing of the pride” becomes “fixing of the price.” Like deciphering James Joyce’s “Finnegan’s Wake,” reading Shea’s lyricals can be both poetic and breathtakingly difficult.

Sometimes Shea is unable to piece together meaning from his lyricals, especially when negotiating with non-native English speakers. To say that he spends much of his life desperately playing a game of catch-up doesn’t begin to explain Shea’s dramatic efforts. That Shea actually succeeds is a miracle brought about by sheer, grind-it-out determination of Olympian proportions.

When Shea finally gets a hearing aid in his mid-30s, it helps but doesn’t eliminate the lyricals. He sits on a bench near a field and listens: “the chorus [of crickets] came from everywhere ... stretching in from over the hills and fields and pouring into my electrified ears. I turned around in circles to hear it, a melody ... coming from every direction.” Once Shea accepts his disability and begins to seek help, his life changes from one of absolute professional focus to one that better values himself and his family.

Eventually Shea decides he doesn’t want to grind out 16-hour days and guzzle Mylanta. He gives up his job, and begins to focus on both his family and his hearing loss. Readers are lucky that Shea took the time to write this masterful memoir, which brings us into a hidden world so few have ever visited. Song Without Words proves that memoir, at its lyrical best, can be a truly wonderful and inspirational literary genre.

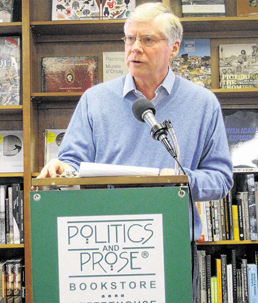

Poetry & Prose Bookstore Interview

Listen to a radio interview with Gerry at the Poetry & Prose Bookstore in Washington D.C. on March 3, 2013.

CBC Radio Interview

Listen to a radio interview with Gerry on CBC Radio's "Tapestry" program on May 17, 2013.

Not quite hearing the full story

The Irish Times

May 29, 2013

Gerald Shea's book Song without Words gives us an insight into the world of those who are partially deaf, writes Deirdre McQuillan

You were a very successful US lawyer. When did you discover that you were deaf?

When I was 33. I had moved into a new job at Mobil Corporation which uniformly gave hearing tests to all new personnel. The nurse rang about 20 different tones into a pair of earphones and I heard only five. After I took them off, she said, or I heard her say, "Were are day, were are your earring days?" She was asking me where my hearing aids were, and I laughed, disbelieving her. Fuller examinations ultimately traced the problem to scarlet fever at six. And that's when, for me, as a child, the most beautiful sounds slowly disappeared. Along with them went consonants and my world grew quieter.

Does scarlet fever always result in deafness?

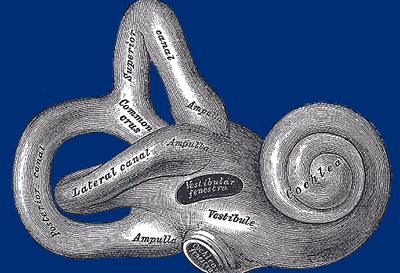

Many people have become profoundly deaf from scarlet fever, including, most notably, Helen Keller, Alexander Graham Bell's mother, and his wife, Mabel. Others, like me suffer significant cochlear damage, others less so; still others escape with their hearing intact.

What sounds do you recall from childhood that you cannot hear now?

The most moving element of my discovery was the day out in the country when I turned on my new hearing aids and rediscovered the sound of crickets. Other sounds followed: the birds, the rainfall, the footsteps, the breaths, the wind and the water . . . they had been absent from my life for almost three decades. Hearing aids help words somewhat, but in general, the struggle is still difficult.

Give some examples of what you call "lyricals" in your book.

The partially deaf interpret what others say through what I call "lyricals," in which those with limited hearing register the wrong words, or nonwords, in lieu of what is actually spoken. For example, if you said,"I thought of that," I could hear, "I lost my hat," a lyrical, and I would have to figure out your words through lip-reading and context. There is poetry in lyricals too, as in"water happens after coral reefs," for"what'll happen after Nora leaves?" We start with our lyricals; and Joyce leads us to his berginsoffs, bergamoors, bergagambols, and bergincellies.

What are the "locusts" you describe?

Tinnitus is a constant buzzing in the ears, and I believe most deaf people suffer from it. I call these internal sounds locusts. As Emmanuelle Laborit, the eminent deaf French actress has said (or signed), "I am noise within and silence without."

What is the most important thing a parent can do for a partially deaf child?

Blackboards and other visual aids are critical instruments of learning for partially deaf children, as are books accompanying speech, cards around the upper walls of the classroom with letters and words. Headsets for television and radio are very effective. But above all the problem needs to be identified, as mine was not.

You play the piano and you sing. How does partial deafness affect your perception of music?

Music is of critical importance to the partially deaf because with hearing aids we can hear it, or important parts of it, without having to search for its meaning, as we must for the meaning of speech. Singing is a pleasure because you can hear your own voice and the voices of those beside you. Song Without Words uses the terms "language in air" and "language of light."

What do they mean?

Air is the medium of speech — without it we couldn't hear each other. The medium of the language of those born profoundly deaf, of sign language, is light.

How difficult is it to use phones and mobiles?

Telephones can be a kind of refuge for many partially deaf people, because of the proximity of the voice you are listening to, amplified by a hearing aid or the (modified) phone itself. The intensity of sound diminishes dramatically with even the shortest of distances. So on a land line, with the other's voice practically in your head, the lyricals are easier. Mobile telephones, on the other hand, are difficult because of weak signals, unclear voices and static. There, it's better to stick to text messages.

But in general conversation, why are hearing aids generally so inefficient?

Amplified sound that hearing aids channel to damaged epithelial cells in the cochlea make sounds louder, but language is still difficult to understand and they pick up a lot of extraneous noise.

Is there any advantage as a writer to being deaf?

The partially deaf may have an advantage at writing because lyricals give us an infinite vocabulary which enables us to slide more easily from one word to another when we are writing in the finite vocabulary of the English language.

Why did you call the book Song Without Words?

Several years ago I played one of Mendelssohn's Songs Without Words for a hearing expert who was examining me and kept a piano in his office. The title from Mendelssohn, elicits a number of ideas: lyricals are often a song without words, or of nonwords or the wrong words; sign language may perhaps be said to be a song without words, though signs are as wholly effective as words; birdsong and the sounds of nature, which I can hear only with my hearing aids, are, for me, songs without words.

Your book has received wonderful reviews. What were the most frequently asked questions on your book tours in the US?

I've received emails from a number of people who have been through the same experience of not knowing they were partially deaf until later in life, and have then changed their lives. Some hearing people have wondered how it could have taken so long to identify the problem not as an intellectual one, but an inability to hear correctly. But as I was growing up and then began to practice law, in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, there was little or no testing, and simply no reference point for an untested partially deaf child or even an adolescent or adult to measure himself against. And many aspects of your life — your sensitivity to loud noises (a symptom of hearing loss), your love of music, your ability to write well, make you think that you were quite normal — that you just had to work harder to overcome your intellectual shortcomings.

Any plans to come to Ireland?

Both sides of my family emigrated to the United States from Ireland in the 19th century. In many respects I feel at home in Ireland, and I am not far away living here in Paris. So I look forward to coming here — to see old friends and to talk about the book.

Book Review

New Statesman

June 12, 2013

Song Without Words: Discovering My Deafness Halfway Through Life

Gerald Shea

"What matters deafness of the ear, when the mind hears." – Victor Hugo

When I met Gerald Shea I was painfully conscious of sound. The book launch had been going for two hours, I had arrived late and — after loudly thanking the coat-check lady and trip-trapping my old Cuban heels across highly polished porcelain tiles — found that his speech was already well underway in the carpeted quiet room of the posh Chelsea house. There were glowers, stares, and the overwhelming cloud of expensive perfume hit me with such force it was near audible. I choked. Shea on his pedestal, mid-speech, never wavered. Jokes. Applause. Shea's recently published memoir laid in piles next to him in a room so quiet I could hear the fabric of a suit as two legs were crossed twelve feet away.

His is a story of a life that could have been completely different, perhaps un-memoir-worthy, had he only known one thing: that he was deaf. By the time he found out, he had already made it through Harvard and Yale and became a successful lawyer. He was not profoundly deaf, but partially; not from birth, but from the age of 5, when a bout of scarlet fever ravaged the epithelial cells in the lower part of the cochlea, the most complex and vulnerable component of the ear. Most vowels and some consonants disappeared from his world. Before their absence was discovered in a routine test in his mid-30s, he put his failure to understand things down to an intellectual defect rather than aural: he thought he heard the same things that other people heard and they were just better at understanding, that he was slow — a fraud in the world of academia. Girlfriends told him he was a bad listener and left him. They were technically entirely correct. If only he'd listened.

His story is like something straight out of Ira Glass' radio show, This American Life — one of those episodes where the music stops on the crucial soundbite where our hero says "and I never knew" and makes you cry on the bus. How different would his life had been, what would he have done instead of guzzling Mylanta for stress-related stomach ulcers while looking at his own exhausted face in the public bathroom and saying: "I wish I were dead"? Professionally, he would have done nothing differently — he would still be a lawyer. But he wouldn't have had to quit in the end and break his own heart.

I've had little experience with the profoundly deaf aside from being the only hearing person at a deaf film festival. The crowd was inexplicably noisy: all the sounds that hearing people learn to stifle are there, unmuted. Everything is louder bar the applause, which is a visual jazz-hands style wave rather than anything audible. Sound doesn't matter here. Being profoundly deaf gives you a separate world to belong to — one with a language entirely of its own — but sound is different in Shea's world, where being partially deaf casts you adrift between two places, the hearing and the other. Said Shea: "We the partially deaf, are not as well off as those who sign, for we have to combine our dual paths of understanding, our eyes and our ears, to get the message in a medium in which we are not at home." Everything moves slower in the in-between, where brainpower is devoted to tasks unnatural to it.

In her Harper's Magazine article in 1954 the American writer Sylvia Wright coined a term for the things that Shea would later call "lyricals." As a child she had misheard a line of the ballad, "The Bonny Earl O'Moray": "laid him on the green" had become "and Lady Mondegreen." She said: "The point about what I shall hereafter call mondegreens, since no one else has thought up a word for them, is that they are better than the original." Reading Shea's book you can't help but agree with her. Lyricals commonly happen to the hearing in the form of song lyrics: kiss this guy, Alex the seal, and, less commonly, a man I know was genuinely confused for an entire childhood as to what could possibly be romantic about the warts on the knees of a woman. He figured it was something he'd understand when he got older when females were no longer an alien species (as it turns out, the wants and the needs of a woman are still as mysterious to him as the warts on their knees). Shea might hear the lyrical "This is summer's wilting youth in a Moma" where others would hear "Mrs. Sommer will see you in a moment." Lee Marvin's line in the old film "Bad Day at Black Rock," "You gotta big mouth, boy — makin' accusations of disturbin' the peace" went into Shea's head as: "You gotta big mouth, boy — makin' of today a song of second peace." Infinite possibilities for poetry and beauty and Edward Lear-ish nonsense lie in the most mundane of daily sentences.

These "lyricals" were how Shea lived his life and studied, too, in a language all of his own: taking notes in lectures (to him, verbatim) and, later, in important legal meetings. He was "freezing the lyricals in time and figuring them out" or, in other words, deciphering them late into the night instead of sleeping, slowly killing his relationships and himself.

The book is not just his own history but also that of the profoundly deaf and partially deaf throughout the ages. He talks about Juan Pablo Bonet in the Middle Ages attempting to make mutes speak simply by forbidding sign language; Roch-Ambroise Auguste Bébian, the first hearing teachers of French sign language in the 19th century; and Helen Keller being made to learn the cumbersome art of fingerspelling instead of her own language of mime. It's a history of how people find a way — their own way — when one sense (or more) is gone.

Toward the end of the launch I got to speak to Shea, a thoroughly polite and deliberately spoken American man called Gerry who now lives in Paris with his French wife. He wears hearing aids, and as long as you speak to him face-on there is no miscommunication. He talks briefly about hearing birdsong for the first time, the tinnitus locusts in his head replaced by something outside of it: in short, the book spiel, the jacket copy. But then he looked wistful and told me about hearing "the sound of [his] own piss in the john" for the first time. I later wonder why he didn't put it in the book given it was his most relatable example of hearing loss so far. A lifetime not knowing that piss had a sound?

Humans communicate. It's not second nature, it's nature. Without that, what is it like to be human? Shea's Song Without Words is as eloquent an answer as we are likely to get.

Book Review

New York Journal of Books

June 24, 2013

Song Without Words: Discovering My Deafness Halfway Through Life

Gerald Shea

"I'm sorry," I said. "Vouchers are priced by the government — at the palace [the seat of the Czech government on the other side of the Vltava River]. I thought they were priced at a hundred crowns each. But you say they have a higher value elsewhere?"

"What?!" said Barclays. "We're not talking about vouchers, man! We're talking about women! The price of women!" "At the hotels!"

Welcome to Gerald Shea's world — the world of the partially deaf.

In his memoir Song Without Words, international corporate attorney Mr. Shea flawlessly and candidly crafts his personal story while painlessly imparting a vast amount of information about the auditory system.

Unbeknownst to him or anyone else, Mr. Shea lost most of his hearing at the age of six after a bout with scarlet fever and chicken pox. Believing that everyone interprets their aural world as he did, Mr. Shea refined his ability to translate verbal language riddles or what he calls "lyricals" into functional meaning.

While he may hear:

"Av a nye tummer?"

Mr. Shea uses his knowledge of language, his intuition, and his intelligence to come up with:

"Have a nice summer?"

But this isn't always so simple, as shown in this conversation with one of his clients. Mr. Shea mentally stumbles through his interpretations of his lyricals after his client said:

"So I've asked you to come down to ease of forewear was apt in."

ease or —

shit

was apt in

what

what's apt in

what's happened

"Gerry?"

see for yourself what's happened

"Fine."

Then the client goes on to say:

"The temperature was sued under the signature, but then some beaut her miss then up with the wreck tore for a northern copy, see? knee deep your help."

This starts a whole new round of lyrical interpretation.

And so many of Mr. Shea's meetings were spent consumed in the frustrating task of working out his lyricals, believing not that he was hard of hearing but simply that he wasn't quite up to the riddling task that other people could do so well.

Stubbornly determined to succeed as a lawyer over the course of three decades, Mr. Shea nearly kills himself, figuratively and literally, as he maintains a lifestyle that leads to the development of stomach ulcers, deep depression, and exhaustion, derailing a possible marriage to a woman he obviously loved dearly.

"Leaning over the sink and pouring the medicine into a tablespoon, I looked at myself in the mirror, white and pale-green skin, red eyes circled in black — a faded flag of some occupied territory, twenty-eight years old and feeling eighty, and looking it, I thought.

"I wish I were dead."

Song Without Words could easily have ended up as tediously frustrating as working out one of Mr. Shea's lyricals — how much can one say about one's life as a corporate lawyer, and how many examples of lyricals need to be read before reaching "enough already!" — but what saves this memoir is his unwavering command of the English language, his exceptional writing ability, and his extensive knowledge of the auditory system.

What makes it shine is the sparkling of humor throughout, the addition of glimpses into his personal life, and the easing of what might be considered arrogance by tastefully illustrating his kindness and humility.

You just can't help but like this man.

Song Without Words is one of those rare memoirs that, once completed, you flip to the back cover hoping for an email address so that you might ask the author out to lunch.

Mr. Shea, are you game?

How To Enjoy Music You Can't Hear

by Gerry Shea

The Wall Street Journal

June 25, 2013

When I came down with scarlet fever as a child, the disease gradually wilted the high-frequency epithelial cells in the lower part of the cochlea. Consonants, which are high-frequency sounds and the markers of our speech, and some vowels, gradually but permanently faded to softness. Before that time, the sounds of crickets, birds, and water were to me unmistakably clear. But as the illness subsided, my young life was transformed into a mysterious play in reverse, shaped by the slow descent of an invisible curtain creating a quieter world — and isolating me within it.

When I returned to school, I wasn't conscious of any change, though birdsongs were thinning out and the sounds of crickets growing dim. Scarlet fever in my case left the cochlear cells that transmit the lower frequencies of speech mostly intact. This gave me the illusion, for almost thirty years, that I heard as others did and that my intellectual efforts to fill in the gaps were a normal practice exercised by all — but that I was singularly slow in making the transitions. I grew increasingly tentative about what people were trying to say, and slid gradually into a particular world.

When others speak, I, and millions of others like me, hear only the contours of an elusive language to which, in the rapid course of conversation, we endeavor to give meaning. The words of our language, what I call its "lyricals," are transitional words, wrong words, and often nonwords that, in lieu of those actually spoken, register in the minds of the partially deaf. They are formed by the stream of vowels that must be translated back into the words that were actually spoken. The lives of the partially deaf are a constant unscrambling of language punctuated by masquerades of understanding.

As I grew older, music, whether I sang it or played it on the piano or wrote light compositions or simply listened to it, became an essential part of my life. I doubt, of course, whether those who hear well can live happily without music. But it is of critical importance to the partially deaf because we can hear it, or at least important parts of it, without having to search for its meaning, as we must for the meaning of speech. While music doesn't carry a message even approaching the precision of words, it has an immediate, readily understandable, profound message of its own.

Beethoven wrote that music may have saved him from taking his own life because his art survived when the distant flutes were fading and he heard the sounds of speech but not words. Mendelssohn emphasized that his Songs without Words expressed ideas not "too indefinite" to put into words but, on the contrary, "too definite." As Kenneth Grahame's gentle Rat exclaimed to Mole while listening to the distant piping of the wind in the willows, "such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet!"

Music is a vital part of the lives of those who are born profoundly deaf as well. Though they cannot hear the songs of the hearing, their music lies in the play of their visual language. Their hands, eyes, and gestures reveal to us that music whether we understand sign language or not. When you observe people signing, they look as if they're conducting mutually responsive, silent symphonies. And the deaf who are also blind, when signing to each other with hands embraced, seem to be conducting a single symphony of their own.

Music is thus in many respects, and in its various forms, a central part of the lives of the deaf. When I was finally examined and got hearing aids, at age 34, they were not a significant help with words, for the devices seemed only to make my lyricals louder. But they did bring with them the musical sounds of nature, the birds, the rainfall, the water, the crickets — the merry bubble and joy of my life as a young child. With them came the violins, flutes, piccolos, and upper strings of piano and harp, making whole what had been half-orchestras and introducing concertos, symphonies, and operas (except for the lyrics, unreachable lyricals) as completed musical compositions.

The effect is spellbinding. The silent violins in overtures become audible; human voices appear in Wagner; sopranos, mezzos, and tenors come to life; bass fiddles and cellos playing harmonics or in counterpoint are relegated to their supporting roles as they lose the melody to the violins and flutes. Peter rivals the Wolf in Prokofiev, and here, too, I become a child again, as my long confusion is spiritually unraveled by the returning, unrepentant, splendorous sounds. Today I know the fullness of its beauty, and I cling to music as if to life itself.

Interview: Radio Open Source

Gerry Shea was interviewed by Christopher Lydon of "Radio Open Source." Below is a link to listen to the interview, followed by a description from the Open Source website.

Gerald Shea's exquisite and affecting memoir of his deafness could be read as an extended riff on Proust's fantasy. About halfway through his 70 years, Gerry Shea realized that he was severely deaf — that he'd been coping somehow, at a price, with an affliction he refused to notice. What he learned in stages was to observe how his brain works — how poetry and music, sign and spoken language and the "commerce of souls" actually work, perhaps for all of us. Shea is a word-master in his own right who comes almost to prefer the pure song — in the tradition of Mendelsohn, too, who wrote the little piano gems "Songs Without Words" and refused lyrics for them. But Gerry Shea got there the hard way — as a lawyer, not a musician.

Through the first half of his 70-years, Gerry Shea misheard almost everything. Example: the opening line of the Frank Loesser song, "I Believe in You," came through as "You are the tear two ties of a keeper of incoming loot" — not "You have the cool clear eyes of a seeker of wisdom and truth," as writ. At Yale, young Shea was a singing star but he didn't belong in class. He took the star history lecturer Charles Garside to be saying that the emperor Charles V "indebited the minstrel stills of this automatic million," when the professor was saying: "Charles inherited the administrative skills of his grandfather Maximilian…"

On such Jabberwocky in ears he didn't know had been damaged by scarlet fever at age 5, Shea went from Yale to Columbia Law and then to a big job with the international firm of Debevoise Plimpton. He had mastered lip-reading and his own mode of translating the garbled nonsense in his ears — his "lyricals," as he called them. But how in the world, you ask, did he avoid having his ears tested for all those years? The deeper riddle in our conversation is: why? And why, when severe deafness finally showed up unmistakably on a job test, he waited a year even to consider hearing aids or any other help. This is the point where the story became, for me, a heart-seizing meditation on afflictions imagined and denied, on identities chosen and clung to — stubbornly and with some cruel effects; and then the joy of letting go.

For me it was always a spiritual or perhaps intellectual problem. I thought everybody else heard what I heard, but that they could translate it and I couldn't. At Yale, I felt in many ways, academically anyway, I probably didn't belong there… I did live in a way in my own world of poetry. Lyricals are really an unconscious poetry. It was the life probably that I did love. Even though the problem of misunderstanding was there, I loved my universe and I still do… As soon as somebody tried to approach my private world of lyricals, I really didn't want to let them in… I think probably because of insecurity, because of fear. Because of my knowledge of myself as perhaps an incomplete human being. Perhaps as someone who was at home with his own internal poetry. It was simply a world that I wanted to keep to myself. I was different from other people, and I was going to live that way and stay that way — except in the law, because I had somehow to earn my bread.

Relief came when hearing aids were virtually forced on him at age 35. The reward was hearing the rest of his music; the flutes, violins and piccolos; the wind in his willows, so to speak, with all due credit to the author Kenneth Grahame.

When I finally got the hearing aids and I realized that the external world was making a lot more sound than I'd heard, it brought me to tears. The first time I wore my glasses with hearing aids in them… suddenly out in that field I felt as if I was not alone and I heard the sound of crickets coming from every direction. It was a beautiful, beautiful sound I hadn't heard since I was a child, a further awakening to me as to who I was and the world I was really living in. 'There it is again,' as Rat says to Mole in The Wind in the Willows. 'O, Mole, the beauty of it! The merry bubble and joy, the thin, clear happy call of the distant piping! Such music I never dreamed of, and the call in it is stronger even than the music is sweet!' That thin clear call has really become the heart of my life. That's what Mendelson was talking about, the definite message of music that carries you with it. The most beautiful part of my life, clearly, is music… The heart of my life. Maybe it always was.

Book Review

San Francisco/Sacramento Book Review

July 10, 2013

Unlike most autobiographical accounts, Shea spends little time talking about himself, and instead exercises the bulk of energy exploring how we express ourselves and convey our ideas verbally as well as non-verbally. For those of us with full range of hearing, the methods of self-expression generally register without challenge. However, for the deaf and partially deaf, forms of speech translate into patchwork confusion — a verbal puzzle to be unscrambled.

In an extraordinary mesh of science and personal reflection, Shea weaves this narrative with self-critical humor mixed with gripping sorrow. Scarlet fever rendered him incapable of hearing the high frequency sounds of most consonants, and deaf to the sounds of song birds and flutes alike. But nobody knew it. Not even him. From the age of six, he simply assumed that everybody heard these lyrical sounds, and assimilated them into real words — only they must be better at it. Somehow he plows through school, struggles through college, passes the bar, all while expending tremendous effort just trying to figure out what people are saying.

As a corporate lawyer working for a prominent New York firm, Shea recalls the anxiety of being unable to comprehend simple conversations around crowded conference tables. Someone asks him a question, which in lyricals sounds like "The temperature was sued under the signature, but then some beaut her miss then up with the wreck tore for a norther copy, see?" He struggles silently to hunt down the meaning while other sidebar conversations ring in his ears with the constant locust drone of tinnitus. "The term-debentures were issued under the sig – ? An impatient client drums his fingers. God, I thought to myself, I must have the IQ of a plant."

In fact, one cannot read this account of Shea's remarkable career — which whisks him from New York to Paris, then on to the Middle East to represent Mobil Oil Corporation — without wondering how anyone could translate the lyricals into real sentences fast enough to give a timely response. This astonishing feat becomes even more incomprehensible with the addition of multiple foreign languages bantering terms of high finance at the bargaining table where Shea, with pen in hand, scribbles out the nonsense he hears so that he can stay up all night translating these alien lyricals into words, hack out a legal document, and present it to the businessmen the following day.

Although written with many a tongue-in-cheek snip at himself that more than once brings even the most curmudgeonly to tears of laughter, Shea relays the intensity of ulcerating pressure in trying to maintain the appearance of a normal-hearing person within the frenetic competition of international banking, with millions of dollars at stake.

Romance brings with it a whole range of complications. "'You're always adrift,' said Beth." He loses them to a handicap he doesn't know he has until finally, at the age of thirty-three, a routine hearing test reveals the truth of his deafness. In Paris he discovers the missing notes of music he yearns for when in lonely exile he cranks up the volume of Strauss's "Nessun dorma" to window-rattling decibels. "The miracle of music at tempestuous volumes became my private secret — made me sing it and dance alone to it… I loved my flutes, piccolos, violins, and harps, and my discovery of the deeper structure of music, but where were the words?"

"Where have you been you instruments you music you heaven of vowels where have you been?"

Through a host of advanced audio technology, and a concerted effort at speechreading, Shea advances in the legal world of words — the alien world where he hunts for meaning among the hearing. But, with the advances of time even these high-tech hearing aids fail to satisfy the burning need to solve the mysteries of everyday speach. In Prague, with international bankers depending on Shea's abilities to iron out their differences, he recognizes his limitation. With a wife and children to support, he broods over the options before him. "At ten o'clock I took a walk as usual over to the Karluv Most, the Charles Bridge, which crosses the river in the middle of the city. The bridge was named in honor of Karel IV, Bohemia's greatest king. Thirty-one stone statues stand guard over those who cross it to go in and out of the old city." It is there in the shadow of Hildegarde of Bingen, the twelfth-century German abbess who kept in her prayerbook the image of Christ curing a deaf man, that Shea finds solace.

His song of a second peace begins with a lyrical from an old Spencer Tracy film and reaches a crescendo on the back of a stallion, racing a stag for the sheer thrill of rushing wind over a French meadow. There, breast to breast with his steed, Shea finds the beat to his song without words in the twin pounding of their hearts, and seizes the courage to leave behind the world of the hearing for the music of light.

Interview on the Mimi Geerges Show

Newstalk Dublin Interview

Listen to a radio interview with Gerry on Newstalk Dublin in October 2013.

Review: West Virginia Gazette

Lawton Posey: Partial hearing loss is a whole challenge itself

November 2, 2013

CHARLESTON, W.Va. -- As I read Gerald Shea's moving book, I remembered sitting on any number of occasions in a soundproof booth with a hearing specialist sending tones to my right ear.

I strained to hear many of these tones, and often entered the booth with a sense of great dread. Will I be worse? Will I be better? How many tones did I miss? Then words of one or two syllables were fed to me. Here they come, and I was to repeat the words as they were said either by the audiologist or a recording. Baseball, toothbrush, she and too, and I would strain to hear and repeat them.

It's rather like an eye chart. Oh, it's just a test. Then came the terrible time when I could hear almost nothing even with my hearing aid turned up full. Fragments of sound came through, and the physician looked grave when he said that I had heard only 10 percent of the words. Then, nothing. Nothing at all.

Ever since I was about 7, until my present age of 78, I have had profound loss in my left ear, and only serviceable hearing in my right. Now, I am a deaf person, but happy to have language, to read, and understand.

Shea, author of "Song Without Words: Discovering my Deafness Halfway Through Life," had similar experiences from the time he had scarlet fever as a young child. However he did not realize that he was deaf. The noises in his head, his inability to understand things people said were all, he thought, things common to all people.

He lived half of his life not knowing that he was severely deaf. He sang in the Whiffenpoofs at Yale. He graduated from Columbia Law with highest honors. He became a lawyer and wordsmith for one of the world's great legal companies, all the time coping in a way that I often coped without realizing what I had done. Coping, guessing, all that is exhausting.

People would talk to him. Some words were clear enough, especially after he got a pair of hearing aids mounted in glasses. I had a set of those. Words in a sentence would become a sort of gibberish that he called lyricals.

In fact, his use of this word unlocked for me the process I would go through when some person would call me to set up a date for lunch. I would guess as to what was said, based on a mental list of restaurants. Shea would hear a string of his lyricals, and then go through a translation process that might involve many hours of work after quitting time. Sometimes, because he became skilled, he could mentally run through a list of guesses that would end with a revelation of what was said.

Having guessed quite a lot, especially on the phone, led one luncheon companion to despair of my understanding anything he, with his English accent said. It was in the pauses that I processed my own lyricals and attempted to make sense of the scrambled words.

Then came a time in midlife when Mr. Shea had to make a difficult decision. For three decades he had guessed, made lists of words, fought to understand, wrote detailed documents, and made lots of money. At home, his French wife, Claire truly understood him and his decisions. He found he could form lyricals in French.

Gerald left the active practice of law and has learned enough American Sign Language to associate comfortably with people at Gallaudet University. He has created reading lists for any of us to use, some of which are in the appendices of his book. He works with hearing persons, those seriously hearing impaired, and with the culturally deaf. In short, he laid aside the stressful features of his former life, which included, as he says "the relentless struggle day in, and day out, year after year, decade after decade to undo riddles requiring unforgiving, constant attention."

After 40 years as a minister and chaplain, I fully agree with Shea's assessment. Understanding for the partially deaf is daunting, tiring

Some of his descriptions may be overlong, and he seems critical of cochlear implants. I hear only by this means. I know that for many severely or profoundly hearing-impaired persons, the cochlear implant opens up the world. After my implant was activated, I heard immediately what the hearing specialist said to me. Yes, she sounded a bit like Mickey Mouse, but I can perceive, with considerable limitations, what people are saying. Language-limited people may not have my experience. I have five friends who have implants and all but one appreciates what they do. I have had to give up music, which has been so very important to me, but that is a small sacrifice to escape the great silence of total deafness.

But there were times when as I perused his words and understanding that I came close to weeping.

WCBN Ann Arbor Interview

Listen to an audio interview with Gerry on WCBN Ann Arbor, recorded on November 15, 2013 and aired as an audio podcast on January 22, 2014.

Salem News (MA) Book Notes

July 11, 2014

Imagine trying to read this sentence if the consonants had been deleted. That's what Gerald Shea, who didn't discover he was partly deaf until his early 30s, has dealt with most of his life.

"I have great trouble with consonants; I hear vowels well," he said. "I thought I was simply slower in making the transition from the lyricals that the partially deaf hear."

"Lyricals" are Shea's name for words as he hears them, which have been distorted by hearing loss and must be translated back into their original form and meaning. He describes his struggles with this process in a memoir, Song Without Words, which he will discuss at the Children's Center for Communication/Beverly School for the Deaf on Monday, July 14, at 4 p.m.

''When I was 6 years old, I had scarlet fever and chickenpox. That was the triggering event," Shea said. Yet, it took him several decades to determine exactly what was wrong."I think that every child has compensating strategies," he said. "If you think your world is a little different, you're going to deal with it by pretending you're like everybody else."

Shea, who moved to Salem with his family after his father died, was very successful at acting like others. He graduated from Phillips Academy in Andover, Yale College, and Columbia Law School, before landing a job at Debevoise and Plimpton, a leading international law firm in New York.

His hearing was always less of a problem at close range, which made it harder to tell that something was wrong. But once Shea started practicing law, where he was expected to negotiate with other lawyers, he couldn't disguise his difficulties. "Whenever I was in a room with two or more people, it was difficult to keep up with them," he said.

Book Review, actiononhearingloss.org.uk

July 2014

Shea's account of his life reads like a thriller. When he was five, scarlet fever deprived him of most of his hearing, but, astonishingly, it took him more than 30 years to discover that other people were hearing much more than he was. As I read through the descriptions of how he interpreted ‘lyricals’ (his term for the nonsensical, yet musical, mostly vowel, sounds he was getting from speech), trying to convert them into sentences with meaning, I kept rooting for him to realize he was deaf. Then, when he did know, but still struggled as a corporate lawyer to make out what was said in meetings and conversations, describing the obstacles of architecture, background noise, individual speakers, and expectations of him, I just wanted him to end the struggle, and leave behind the legal work he was doing so well, but at great personal cost.

Eventually, Shea did leave his profession, which gave him time to research and present to us this in-depth, essential information about sign language, how the ‘half-hearing’ interpret speech, or how we hear when speaking a foreign language. His informed reflections sometimes verge on poetry: “I turned the hearing aids on and off: from noise without and silence within, to noise within and silence without, and back again.” Shea has presented us with a cogent, beautifully literate, and breakthrough book of the philosophy of being a partially deaf person.