Class News

1964 Class Council applauds emotional presentation by Urban Resources Initiative summer intern

At its annual meeting on February 7, your Class Council enjoyed a very informative and passionate presentation by Katie Beecham, the 2014 summer intern at Urban Resources Initiative (URI) whom our Class subsidized with a financial contribution. URI is overseen by Colleen Murphy-Dunning, who is Program Director, Hixon Center for Urban Ecology at Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

For the narrative and visuals of Katie's presentation, see below.

Classmates may recall from previous Class News articles and Class Notes that URI is an organization that our class supports with an annual contribution, as we have for the past three summers. It was very compelling to see evidence of the community benefit and the deep commitment of this intern. As with the other organization that our Class supports (Squash Haven), URI combines five criteria that your Council deems worthy of support:

- A close affiliation with Yale

- A direct involvement in, and benefit to, the New Haven community

- Support for sustainable environmental practices

- Educational benefit for the young people who participate

- Direct board and advisory liaison with one or more of our Classmates

In the case of URI, Chris Getman has been a URI board member and Mike Price has been very involved with this and earlier SF&ES programs. Classmates are encouraged to consider URI for direct personal contributions. Please contact Chris Getman or Mike Price if you are interested.

Slideshow

Narrative

Community Greenspace: The Art and Science of Breaking Ground

Katie Beechem

Community Greenspace Intern, Summer 2015

Urban Resources Initiative, New Haven, CT

I’d like to briefly introduce myself, but first I want to bring your attention to this quote by Rebecca Solnit, one of my favorite writers and environmental and human rights advocates. She writes that, “sense of place is the sixth sense, an internal compass and map made by memory and spatial perception together.” We often take it for granted, but how interesting is it that when most people introduce themselves, they start by telling you where they are from. It’s as if this sense of place — this internal compass made of spatially bound memories — is intricately woven into our own identities. This may seem like a tangent, but I’ll describe later how I think this relates to the Greenspace program. But let me first describe to you where I am from.

Most of the time, I tell people that I am from Baltimore, MD, but this is only a half-truth. I was born in Illinois and moved to Nashville when I was very young. I became a competitive gymnast from a young age and continued to practice gymnastics when my family moved to Oregon when I was twelve. The pressure of competing ultimately drove me to quit gymnastics after 11 years and take up dance. But my perfectionist tendencies, and the desire to be lean as gymnast and a dancer proved to be a near-lethal combination, and grew extremely sick in 2002. Despite the fact that I spent most of my time in and out of hospitals during these years, my dad and I did manage to take a number of hiking and backpacking trips together, and I came to realize that, if I was going to have any chance of beating this disorder, it was going to come from redirecting my energy toward my passion for nature and the outdoors.

I moved to Baltimore for college, where I earned a bachelors degree in biology, made the best friends of my life, explored every square of the Gwynns Falls Park, improved my health, fell in love for the first time, and landed my first truly incredible job with the Baltimore County Forest Sustainability Program. After working with them for three years, I was inspired me to return to school, where I have continued to pursue my interests in community forestry as a tool for social and environmental justice.

What I intend to convey in sharing this is that the memories and relationships formed within a place — whether it is a city or a neighborhood or a block — have the power to fundamentally transform our internal compass, our own sense of place. I love my family in Oregon to no end, but I identify most positively from Baltimore.

I want to revisit this theme and others later, but I know that you can’t start a book by reading the last chapter. So what I’d like to do first is paint a few pictures for you that illustrate some of my experiences working with the Greenspace program this summer. I’ll then consider them as they relate to these questions, which I think really start to capture the essence of what the program is all about — at least from my point of view. And that is: what does Greenspace mean for communities? What does it mean for volunteers? And, because I can’t resist, what has it meant for me?

To provide a bit of an overview, the Greenspace program works with about 50 different neighborhood groups throughout New Haven each summer. The groups are concentrated primarily in middle and low-income neighborhoods, and each group has one or two leaders from within the community. I was one of seven Greenspace interns, who work with these leaders and the group members to pursue projects initiated by the group.

We helped to guide the groups to ensure that the projects conformed the three central goals of the Greenspace program, which are restoration, stewardship, and community building. And we received training and support on these topics from the Greenspace program manager, Chris Ozyck, prior to and throughout the duration of the program. Each group met once per week for two or more hours to work on their projects. And throughout the summer, we — as interns — provided the tools, materials, and technical support required to facilitate the group’s progress.

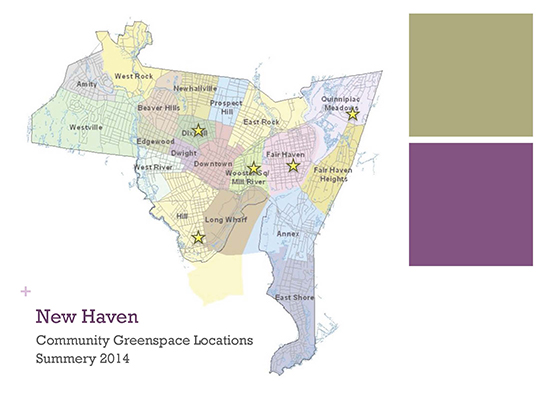

I worked with five different groups this summer, each of which is shown here on the map. These included groups from the neighborhoods of Dixwell, the Hill, Wooster Square, Fair Haven, and Quinnipiac Meadows. They all had different projects and different group dynamics, but I’ll say that it was a real privilege and pleasure to be able work with each and every one of them. It pains me a little to only have the time to talk about a couple of them, but I’ve chosen groups that I think illustrate a range of work and that really exemplify the essence of the program to the fullest extent.

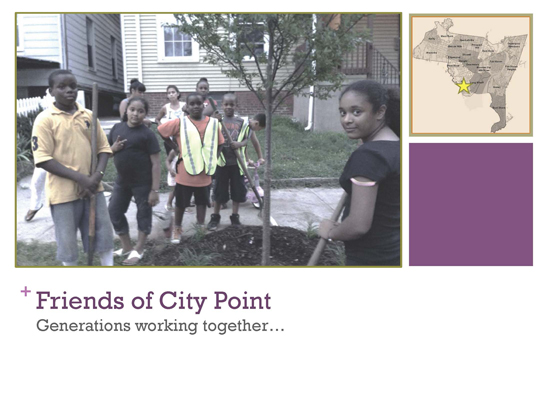

The first group I want to tell you about is the Friends of City Point. City Point is a neighborhood located in the southwestern part of the city. Throughout most of the 1800s, it was known as Oyster Point, on account of its robust oyster industry. As the industry declined in the 1900s — and as the neighborhood tried to rebrand itself as a new fashionable suburban district — the area came to be known as City Point. Now, the neighborhood is often considered part of a much larger block known as the Hill, or Hill South. It is home to an eclectic mix of ethnicities, but it is still in the process of recovering from urban decay, which plagued many of New Haven’s neighborhoods during the Great Depression and the rationing of WWII, when homeowners lacked the resources to maintain their homes and when the post-war policies of the federal government encouraged highway construction and suburban sprawl.

The Friends of City Point is a group that has been active now for five consecutive years, and they had ambitious goals this summer. On the day that I first walked the streets with the group leader — who self-identifies as a “guerilla gardener,” and who knew by name almost every person we encountered — we marked more than twenty locations within a mere four blocks that had potential for street trees. The group worked primarily on the side streets running perpendicular to Howard Avenue, planting two trees almost every week. While Howard Avenue has some of the largest oak trees I’ve seen in the city, the side streets are quite a different picture. In the heat of that bright afternoon, I’m afraid the only shade we had was from our own hats.

The group met every Wednesday evening, and I learned quickly to pack the truck with the shovels and gloves easily accessible. And that’s because as soon as I pulled up, I was swarmed by some ten to fifteen kids, all ready to get to work! I’d say the “tree truck,” as they called it, had a popularity even the ice cream truck couldn’t rival… which means a lot in City Point!

The first couple of weeks were a real challenge as we struggled to organize, but I soon learned the importance of assigning tasks. With a small army of car lookouts, glove distributors, hole diggers, wheelbarrow fillers, truck monitors, tree movers, and wire basket cutters, we settled in to what could best be as organized chaos. I did my best to learn their names, and each night, I made a point of acknowledging each of their contributions. What amazed me then was how enthusiastically they embraced their roles! One of the boys, Xavier — a really quiet kid — begged his parents to skip a little league game one night so he could continue filling buckets of water. And Jayla and Sasha — late additions to the group — insisted on finishing their job of removing the tree’s wire basket, even as I watched their small arms strain with the effort.

A handful of adults helped with the tree plantings as well. One night, one of them pointed out the small oyster shell fragments that they were digging up, and several of the kids made a point of collecting them. Then they would walk home each night with these bulging pockets. I couldn’t help but smile at the poetry of this: of digging up oyster shells a hundred years old to plant a tree that would grow for a hundred more…

In all, the Friends of City Point ended up planting 17 trees over the course of the summer, in addition to maintaining the trees planted in previous years. This took tremendous effort and was more than the group had ever done in a season. I remember the feeling of sitting on a group member’s porch on the last workday, as we ate cake in celebration of the group’s 5th “birthday.” It was late and still no one wanted to leave. Not the kids, not the adults. And we took picture after picture by the truck and by the trees. And it made me realize how much the work meant to them. And how much I’d miss them.

The other group I’d like to tell you about is Fair Haven Neighbors in Action. Fair Haven is on the east side of the city between the Mill and Quinnipiac Rivers. On the whole, Fair Haven is also quite mixed ethnically and socioeconomically. But the blocks in which we worked were predominantly Hispanic and low income. Mayor John DeStefano observed in 2010 that, more than any other neighborhood, Fair Haven was rooted in and contained within itself. And I’d have to say that, based on my experiences, I agree. When I mentioned to one of the group members that I was working with another group in the Wooster Square neighborhood, they didn’t have any idea where that was, despite the fact that it borders Fair Haven directly to the west.

Fair Haven Neighbors in Action has also been working now for five consecutive years. The group has focused primarily on planting street trees and remediating yards that are contaminated with lead. Most of the older houses in New Haven were painted with lead paint, and as the paint chips off or wears away, it accumulates and persists in the soil. Lead remediation is an intensive process that involves, in many cases, skimming off the top layer of soil, replacing it with new soil, and planting woody shrubs that help to filter and decontaminate the soil.

The pictures on the bottom right show the “before” and “after” of one of the group’s remediation projects. The family was actually hesitant to participate at first. The evening that we arrived to do the project — which they had helped to plan — the parents weren’t home. When they finally did arrive almost an hour later, we were worried that they might have second thoughts about it. Taking on a project like this — with neighbors they didn’t know very well yet — was a scary endeavor. The family had never planted anything before, and they were worried that they wouldn’t know what to do. They felt helpless, and vulnerable.

But they did decide to take that leap of faith — to trust us and to trust their neighbors — and when they did, it was as if their whole demeanor changed. With great courage and great humility, they learned how deep to dig holes for the plants, how to massage the roots before planting, how to water, how to spread mulch. And armed with that information, they ran with it. I wish I had a picture to show it, but I was walking down their street soon after the program had ended, and their yard was extravagantly embellished with annuals, colorful pinwheels, little statues, lights! And sure, it may have been gaudy, but to me, it was the most beautiful thing. Because what it showed was a sense of pride in their place, a real sense of ownership and care. They had stopped hiding. And as it would turn out, the father and his son also became two of the group’s most consistent members, showing up almost every week to help plant trees or work in other neighbors’ yards.

I was nervous about working with this group at first for a number of reasons. For one, there had just recently been a change of leadership, which can be a tough transition for any group. Second, my Spanish was elementary at best, and some of the group members spoke very little English. Third, the group had joined up with another group on the east side of Ferry Street, the main north-south artery through Fair Haven. And Ferry St. was more than just a geographic separation. The residential demographics on either side of Ferry were quite different, and while I saw the merger as an opportunity, I was also a little worried about how well the two groups would mesh.

I’m really happy to say that this group surpassed all of my expectations. The new leader of the group, Ed, was quiet and unassuming, he always greeted people with this huge grin, and his work ethic was unmatched. Even when he wasn’t planting trees, he was working on his house, helping a neighbor with a fence, renovating his shed, or getting involved with church functions. It was clear that the group members had a lot of respect for him, and they followed suit, showing up even in the pouring rain to go to work and plant a tree. One of my favorite photos is on the top left, where Maria, one of the group members, is working on a planting hole with a pick axe while using a trash bag to keep her head dry.

The language barrier didn’t turn out to be a problem either. It felt scary to expose my weakness like that at first — I had to use my hands and body to communicate much more than I used my limited vocabulary. And, likewise, some group members struggled with their limited English. But in a strange way, in making ourselves vulnerable to each other, we connected over it. And at the end of the day, when the trees got in the ground, and it felt like that much more of a victory.

Finally, the merger of two groups on the east and west sides of Ferry St. turned out to be surprisingly successful. We spent every other week on either side of the street, and it was touching to see group members go through the tough labor of planting a tree located three blocks from their own. Then about half way through the summer, the group helped to coordinate a block party. The police blocked traffic on either side of the block and opened up one of the fire hydrants for the kids to play in the water. We planted two trees that day, and the mayor even stopped by to acknowledge the neighborhood’s work.

Like City Point, Fair Haven Neighbors also exceeded previous years’ planting efforts. In 2013, they planted 9 trees. Last summer, the group planted 17 trees — 5 of which required concrete removal — and remediated 3 front yards. It wasn’t easy, but as we lounged in Ed’s hammock eating watermelon after the last workday, I think we all got the feeling that it was every bit worth it.

Maybe it’s obvious from these stories, but I have no doubt in my mind that this program has a profound impact on communities. URI or the city might see this work as restoration, but community members — the people who do the work — see it as beautification. It is truly incredible to witness the transformation of these spaces from areas of neglect into areas of immense pride. And to guide the members of the community as they develop the vision and do the work. Because it’s in the struggle, in the breaking of the ground, and in the reliance on neighbors, that groups ultimately strengthen their own sense of place, their own internal compass. And every thumbs up, ever honk of a horn, reinforces this sixth sense, this sense of investment and belonging in a place.

There is another way that Greenspace impacts communities, which I didn’t fully appreciate until I worked with the Quinnipiac Meadows neighborhood group. This summer was the group’s first year, and they wanted to beautify a corner bus stop, shown here on the top right. This area had been an eyesore for the community for years, collecting trash and hiding illicit activity that went on in the trees. It also served as a cut-through for cars, making it dangerous for kids waiting for the bus.

Many neighbors along the street didn’t want to get involved at first. In my naiveté, I thought they would be quick to get on board. After all, they had complained about the street corner at the community meeting. But instead, they were skeptical. In their eyes, they were a “forgotten street,” one the city didn’t care to maintain or clean up. They had thrown up their arms. “What’s the use in trying?”

So we started small. We planted one tree at a time with a small, dedicated crew. And soon enough, the community realized that every week, the trees came. Every week, someone was showing up. Someone, at least, seemed to care. And at that point, it was like the floodgates opened. Now they had plans to plant two trees a week. And to lay a stone dust path. And to make a sign, and plant a garden. And finally, I had to say, “listen, we can only do so much. We’ve got to save the rest of these ideas for next summer.” But you can see the way they transformed the space. The group planted seven trees, a small garden, spread 4 yards of mulch, and laid a stone dust path. Even I was shocked with how far they’d come.

What this demonstrated to me was a concept I’d first learned about through the writing of Clarence Stone, an urban policy scholar. To paraphrase, he wrote that people will speak when they believe they will be heard. And they’ll act when they believe they’ll make a difference. In other words, poor, even desperate, conditions alone are often not enough to compel a community to act. But poor conditions — together with the belief that action will create change — are a powerful combination. I think that the Greenspace program gives communities the opportunity to believe. To believe that their actions can and do make a difference. And like the Quinnipiac Meadows group, once they start to trust each other and see the fruits of their work, it’s like a whole new world has opened up to them.

So how does the Greenspace program affect communities at the individual level? Typically, when we consider how greenspaces affect people, we often think about the physical aspects of health. We know that trees and plants remove pollutants and clean the air. We know that streets with closed canopies experience lower, more comfortable air temperatures in the summer. And that tree canopy density correlates with lower instances of asthma. And that trees filter toxins and clean the water… and cleaner water means healthier crops, healthier fish, and healthier drinking water.

And these are extremely important benefits, ones that future generations may look back and thank us for (if we’re lucky). But I don’t think that this is why most volunteers contribute hours of their free time each week, nor do I think that the 17 new trees at City Point this year will immediately impact individuals’ physical health. But I do believe that Greenspace activities can improve individuals’ quality of life dramatically in other ways. Call it mental health, emotional health, or spiritual health — I don’t know which — but one thing that really struck me — and stuck with me — this summer was the confidence with which Greenspace volunteers carried themselves in their neighborhoods. And it wasn’t a self-righteous confidence, but more of a quiet, satisfied, self-assurance more than anything — the kind of poise that comes from knowing others and being known. Because these volunteers, I believe, have a secret — and it is a secret that most of us have either forgotten or denied. And that is that — despite what we’re told and despite how we’re conditioned in this society — we do, in fact, need each other.

This may seem strange, but one of my favorite things to watch this summer was someone struggling to maneuver a 300 lb. tree off the truck. Because as smart, resourceful, and powerful as they may be, it simply isn’t a one-person job. And after trying, and looking around, and trying again, they would inevitably ask, “can someone lend me a hand?” We are told to be strong, to be tough, to do it ourselves… but I believe that this is exactly what prevents us from truly, deeply connecting with others, wreaking havoc on our quality of life even if we breathe the cleanest air and drink the cleanest water.

Brene Brown, a professor of social work at the University of Houston, and one of my favorite writers, suggests that, “staying vulnerable is a risk we have to take if we want to experience connection… vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity, and change.” I love this aspect of the Greenspace program that pushes volunteers beyond their comfort zone and exposes their vulnerabilities — whether they like it or not. Because in doing so, it collapses the walls that isolate them. It opens up this whole new space for connecting, deeply, with one another. And if this doesn’t improve quality of life, I don’t know what does.

Perhaps it goes without saying that I have learned so much from this program. The task of working in communities, of loading and unloading trucks, of making quick decisions, of dealing with turns in the weather and upset volunteers and flat wheelbarrow tires, and of juggling the needs and schedules of fifty groups among seven interns with only five trucks… was both extraordinarily challenging and immensely rewarding. Like maneuvering a tree off a truck, it couldn’t have been done alone, and many times I was tested, forced to expose my own limitations and weaknesses, and request the help of my peers. And many times, I returned the favor. So perhaps it comes as no surprise that we interns have become each others’ closest friends, united by a strong, enduring connection forged through struggle and vulnerability.

I’ve learned that for families, individuals, and communities struggling to get by, the Greenspace program may not lift them out of poverty. Nor may it solve all of the city’s environmental problems. But I believe that it can and does promote residents’ sense of place and belonging, contribute to a positive self-identity, give residents the confidence that their actions can make a difference, and forge deep and enduring relationships, all of which reduce stress and enrich lives.

Finally, I’ve learned that leading isn’t about knowing everything, it isn’t about being perfect, and it isn’t about making things easier for everyone else. Instead, it’s quite the opposite: it’s about listening, about being honest and supportive. It’s about acknowledging when you’re wrong or unsure. It’s about modeling hard work, and allowing others to struggle through things sometimes. Brene Brown says that, “vulnerability sounds like honesty and feels like courage.” And for all of their hard work — for all of the trees and flowers and shrubs — what I respected most about my volunteers and fellow interns was in that the moment they put their shovels down, wiped their sweat, and bravely said “I’m getting tired. Will someone lend me a hand?” For all of the conversations about planting techniques, soil amendments, good pruning practices, and watering schedules, it turns out that we were the ones who were growing after all.