In Memoriam

Henry N. “Skip” Edmunds

Skip Edmunds

Yale graduation, 1964

January 8, 2023

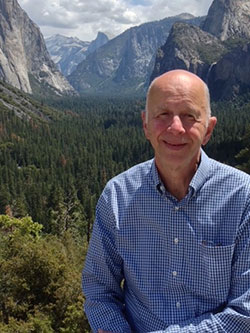

Henry Newton Edmunds ’64 died on October 20, 2022. At Yale he was known as “Skip” or “Emu.” There has been no published obituary. He was a resident of San Marcos CA (near San Diego) at the time of his death. His widow, Lin Henderson, whom he married in 2015, sent us the photo below from their honeymoon in Yosemite.

We were notified of his death by Art Boylston ’64, his freshman roommate, who wrote the following remembrance.

Remembrance of Skip Edmunds

by Art Boylston ’64

Henry and I met the summer before we started at Yale because his girlfriend’s parents were friends of my parents. I roped in Doug Nohlgren, a friend from AFS, and Don Hess, a friend from Exeter, to form a roommate group . Henry was known as Emu, a high-school nickname, by us and by a few first-year friends, but he preferred Skip and so he shall be here.

Skip and I had to try to inhibit Doug’s Olympic-class bed-bouncing. Three alarm clocks, hiding one in a drawer, barriers of pillows or cushions — all failed. Whatever we tried Doug always got back into bed and then complained when he missed an early lecture. Skip and I also shared the famous Yale Station pay phone phenomenon but otherwise first term went uneventfully.

Skip on his honeymoon

in Yosemite in 2015

Then disaster struck Skip, the first of a lifelong series of catastrophes which helped define his character. He got mononucleosis. He had hoped to try out for freshman basketball and then high jumping in the spring. But the virus left him so tired and weak that just getting to class and studying was difficult. His academic results suffered but he managed to hang on just enough to get through the year. Although it was not named “long mono,” he had the predecessor of “long COVID.” In Skip’s case the effect lasted into sophomore year when he undertook the incredibly demanding Yale Chemistry major. He recovered gradually and by junior year he made the Dean’s list and in his senior year was twice listed as a ranking scholar, which propelled him into the prestigious PhD program of the Biochemistry Department at Cal Berkeley.

But four years into his program another disaster struck. His supervisor was murdered. At the time, if you lost or changed your supervisor, you had to abandon your project and start over from scratch. Fortunately, he had just enough data to write up his thesis on the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase. When this became the basis for a widely used blood-alcohol test, he received a lump-sum payment and hurriedly invested it into one of those oil-well tax dodges that was guaranteed to produce bounteous tax-free income. It was a scam. He lost the lot.

Skip responded to this disaster by suing, despite predictions that he would never recover his money. When, against the odds, he did, he used it to fund an MBA at Stanford. The outcome of this disaster was that he was now a formally trained biochemist with advanced business skills, just the right combination for employment in the emerging world of biotech California. He held a number of positions, usually as chief financial officer but occasionally as CEO, in many small start-up firms. His forte was ensuring that the company’s financial returns and production protocols met FDA standards. At times he also helped design clinical trials to ensure that the results would be accepted.

We lost sight of each other for about 25 years. When I looked him up in 2008 he was based near San Diego but was working with a small German pharmaceutical start-up which was trying to pioneer a new cancer therapy. His long-term partner, Nadia, had breast cancer and he hoped to be able to try this new drug on her. He eventually revealed that he spent much of his time combing the biochemical and immunological literature to find potential treatments for her. He had even made one or two that looked promising.

To no avail. Nadia died in 2012, not long after Skip had undergone his own medical ordeal. He had developed progressive coronary artery disease which required a quintuple bypass procedure. His cardiac rhythm became unstable and he needed a defibrillator pacemaker which left him with left-arm pain for months. He went quiet after Nadia’s funeral and memorial service so that I feared that the two events had finally crushed his spirit.

Not so. After a little over a year I got a jubilant email. He had met, married, and moved in with a widow, Lin Henderson, who lived just ten miles up the road. They made trips to Canada to visit her brother who returned the favor. They went for long walks and played “flog,” Lin’s name for the geriatric golf that they enjoyed. Skip was at peace, relaxed and very much in love. We exchanged regular emails, often with cartoons or jokes that we had come across. When the COVID epidemic struck, Skip began to use his science skills to comb the literature for news of promising treatments which he disseminated widely among a group of friends. His attitude towards lockdown became clear when the rules stated that you were only allowed six guests for Thanksgiving dinner but could have thirty to a funeral. We were all invited to the funeral of his pet turkey to be held on November 26.

On October 17, 2022, I got an email from Skip. He was in hospital and knew he was dying. He reminisced a bit about our long friendship and thanked me for being his friend. He died three days later.

Looking at this email again I can see the man I knew. Lin said he was the kindest man she had ever met, and this was true. Facing his final disaster, he thought of his friends, reached out, and sent us kind messages. He wanted us to know how much he valued us.

Emu was really one of the good guys.