In Memoriam

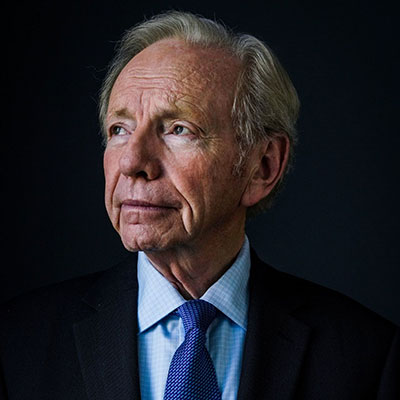

Joseph I. Lieberman

Joe Lieberman

Yale 1964 graduation

Joe died on March 27, 2024 in New York City due to complications from a fall. We honor his memory with the following remembrances:

- Obituary, The New York Times

- Remembrance by Joe’s son Matthew

- Video of Joe's funeral service

- Article from the Yale Daily News

- Letter from Yale’s Jewish Chaplain

- Remembrance by Edward Massey ’64

- Remembrance by Ward Wickwire ’64

- Remembrance by Bill Kridel ’64

- Essay by Joe, 60th Reunion Book

- Essay by Joe, 50th Reunion Book

- Essay by Joe, 25th Reunion Book

Obituary

Joseph I. Lieberman, Senator and Vice-Presidential Nominee, Dies at 82

He served four terms in the Senate from Connecticut and was chosen by Al Gore as his running mate in the 2000 election. He was the first Jewish candidate on a major-party ticket.

The New York Times

March 27, 2024

Senator Joseph I. Lieberman with fellow senators at the Capitol building in Washington in 2010. After serving three terms as a Democrat, he was re-elected as an independent in 2006.

Joseph I. Lieberman, Connecticut’s four-term United States senator and Vice President Al Gore’s Democratic running mate in the 2000 presidential election, which was won by George W. Bush and Dick Cheney when the Supreme Court halted a Florida ballot recount, died on Wednesday in Manhattan. He was 82.

His family said in a statement that the cause was complications of a fall. His brother-in-law Ary Freilich said that Mr. Lieberman’s fall occurred at his home in the Riverdale section of the Bronx and that he died at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in Upper Manhattan.

At his political peak, on the threshold of the vice presidency, Mr. Lieberman — a national voice of morality as the first major Democrat to rebuke President Bill Clinton for his sexual relationship with the White House intern Monica Lewinsky — was named Mr. Gore’s running mate at the Democratic National Convention that August in Los Angeles. He became the nation’s first Jewish candidate on a major-party presidential ticket.

Mr. Lieberman with Al Gore in Nashville in July 2000,

when Mr. Gore formally introduced Mr. Lieberman as his running mate.

In the ensuing campaign, the Gore-Lieberman team stressed themes of integrity to sidestep the Clinton administration’ scandals, and Mr. Lieberman urged Americans to bring religion and faith more prominently into public life.

The ticket won a narrow plurality of the popular votes — a half-million more than the Bush-Cheney Republican ticket. But on the evening of Election Day, no clear winner had emerged in the Electoral College, and an intense legal struggle took center stage.

After weeks of dispute, it came down to the results in Florida, where fewer than 600 votes appeared to separate the opposing candidates. In an unsigned landmark decision on Dec. 12, the United States Supreme Court ruled, 5-4, that different standards of recounting in different counties had violated the equal protection clause of the Constitution and ordered an end to the recounts. The decision effectively awarded Florida’s 25 electoral votes, and the presidency, to Mr. Bush.

“It was a miscarriage of justice on two levels,” Mr. Lieberman said in a 2023 interview for this obituary. “One was that the Florida Supreme Court had already ruled in our favor to continue the recounts, and the other was that it was an extrajudicial political decision made in the crisis of a transition of power, and out of line with precedents of the Supreme Court.”

Mr. Lieberman sought the 2004 Democratic presidential nomination but lost multiple primaries and withdrew from the race in February. He believed his support for the war in Iraq had doomed his candidacy.

Even his standing with Connecticut voters had slipped. Running for a fourth Senate term in 2006, he lost the Democratic primary to an antiwar candidate but won in a stunning upset in the general election as a third-party independent on the “Connecticut for Lieberman” ballot line.

Mr. Lieberman at the Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minn., in 2008.

He endorsed his friend Senator John McCain of Arizona for the presidency.

With his presidential hopes in tatters, Mr. Lieberman in 2008 attended the Republican National Convention and endorsed his friend, Senator John McCain of Arizona, for the presidency. Mr. McCain had Senator Lieberman vetted as a possible running mate but ultimately chose Gov. Sarah Palin of Alaska and lost the election to Senator Barack Obama.

Mr. Lieberman, a virtual outcast in his own party, had stopped attending Democratic Senate caucuses. But after a humbling meeting with the Senate majority leader, Harry Reid, he was allowed to keep his Homeland Security Committee chairmanship and resumed caucusing with the party.

Mr. Lieberman in the U.S. Capitol in 2012.

Approaching Senate retirement, he endorsed no one in the 2012 presidential election, but he supported Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in her presidential run against Donald J. Trump in 2016 and Vice President Joseph R. Biden’s victory over Mr. Trump in 2020.

During his Senate tenure from 1989 to 2013, Mr. Lieberman was an independent who wore no labels easily. He called himself a reform, centrist, and moderate Democrat, but he generally sided with the Democrats on domestic issues, like abortion choices and civil rights, and with the Republicans on foreign and defense policies.

He supported Israel and called himself an “observant” Jew but not an Orthodox one because he did not follow strict Orthodox practices. His family kept a kosher home and attended Sabbath services. To avoid conveyances on a Sabbath, he once walked across town to the Capitol to block a Republican filibuster after attending services in Georgetown.

Many Democrats criticized Mr. Lieberman’s support for the war in Iraq, but admirers said his strengths with voters lay in his rectitude, his religious faith, and his willingness to compromise.

Mr. Lieberman stood behind President George W. Bush in October 2002

when he signed a resolution authorizing military operations against Iraq.

Mr. Lieberman was later criticized by Democrats for his support for the war.

“He may be a thoroughgoing moderate in his politics, but he is a true conservative in temperament and style,” The New Yorker said in a 2002 profile. “His world is an orderly place where people wait in line, take their turns, and generally behave themselves.”

After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Mr. Lieberman led the Senate effort to create a new Department of Homeland Security, a cabinet agency that consolidated 22 federal entities to counter terrorism and coordinate responses to natural disasters. He was named chairman of the new Senate Committee on Homeland Security in 2003.

He also cast the 60th and deciding vote under Senate rules to pass Mr. Obama’s Affordable Care Act in 2010 — the most important package of health-care legislation since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.

“As a Democrat, Joe wasn’t afraid to engage with Senators from across the aisle and worked hard to earn votes from outside his party,” Mr. Bush said in a statement after Mr. Lieberman’s death. “He engaged in serious and thoughtful debate with opposing voices on important issues.”

A Yale-educated lawyer, Mr. Lieberman began his political career in 1970 by unseating Ed Marcus, the Connecticut State Senate’s Democratic majority leader. He credited a young Yale law student on his staff, Bill Clinton, with engineering his crucial primary victory.

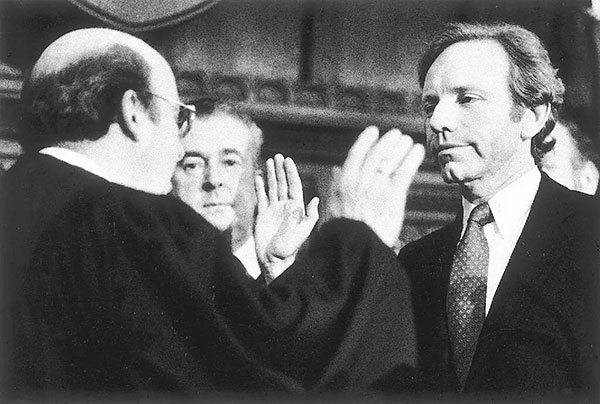

Mr. Lieberman was sworn in as Connecticut’s attorney general in January 1983.

After a decade in the State Senate, the last six years of which he was the Democratic majority leader, Mr. Lieberman lost a race for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1980. Three years later, he was elected attorney general of Connecticut, the first to hold the post full-time. In that office, he defended consumer and environmental protections and was re-elected in 1986, but he left the job after winning his first Senate race in 1989.

In the Senate, he supported free trade and unions and led a campaign against sex and violence in video games. The effort generated a video ratings system in the 1990s and national publicity for Mr. Lieberman.

His campaign for a second term in 1994 scored the largest landslide ever in a Connecticut Senate race. He collected 67% of the ballots and buried his foe by 350,000 votes. For six years, he was chairman of the Democratic Leadership Council. And in 1998, when Bill Clinton’s affair with Ms. Lewinsky broke, Mr. Lieberman chastised the president publicly.

“It was a very hard thing for me to do because I liked him,” he told Bill Kristol, the neoconservative commentator. “But I really felt what he did was awful.” A remorseful Mr. Clinton later called Mr. Lieberman, saying, “I just want you to know that there’s nothing you said in that speech that I disagree with.”

In 2000, while running for the vice presidency on Mr. Gore’s ticket, Mr. Lieberman simultaneously won a third term in the Senate handily, with 64% of the vote, turning back a challenge from the Republican Philip Giordano. But six years later, Mr. Lieberman hit a wall seeking a fourth term. Ned Lamont, a Greenwich businessman and critic of the Iraq war, won 52% of the vote in a primary.

Ordinarily, losing a primary is a death knell. Campaign donations dry up, colleagues and the press turn away, and the loser drops out or runs as an independent.

However, Mr. Lieberman refused to give up. Many voters saw the race as a referendum on President Bush, whose claims that President Saddam Hussein of Iraq had weapons of mass destruction had been disproved, suggesting that he had taken the nation to war under false pretenses. With wide Republican endorsements, Mr. Lieberman easily defeated Mr. Lamont in the general election for one last Senate term. (Mr. Lamont became Connecticut’s governor in 2019.)

Mr. Lieberman celebrated in Hartford

after being re-elected to the Senate as an independent in 2006.

Mr. Lieberman was also instrumental in Mr. Obama’s successful 2010 effort to repeal a 17-year-old “Don’t ask, don’t tell” Armed Forces policy, which had forced gay and lesbian service members to be closeted or face discharges.

On Jan. 2, 2013, Mr. Lieberman gave a parting address in the Senate. “It was a lonely farewell,” The Washington Post said. “As Mr. Lieberman plodded through his speech, thanking everybody from his wife to the Capitol maintenance crews, a few longtime friends trickled in.” They included Senators Susan Collins, John Kerry, and John McCain.

“The sparse attendance wasn’t unusual for a farewell speech,” The Post said, “but it was a sad send-off for a man who was very close in 2000 to becoming a major figure in American political history as the first Jew on a major party’s national ticket. He was denied the vice presidency not by the voters but by the Supreme Court.”

Mr. Lieberman in 1960

as a senior at Stamford High School.

Joseph Isadore Lieberman was born in Stamford, Conn., on Feb. 24, 1942, the oldest of three children of Henry and Marcia (Manger) Lieberman. His father owned a liquor store while his mother managed the home.

Joe and his sisters, Rietta and Ellen, grew up in a working-class section of Stamford. He attended Burdick Junior High School and Stamford High School, where he was elected president of his sophomore and senior classes, joined a debating club, and was salutatorian of the class of 1960.

At Yale, he majored in political science and economics, joined the N.A.A.C.P. and the Democratic Party, and was the editor, chairman, and chief editorial writer of The Yale Daily News, writing about defending the civil rights of Black Southerners. He graduated magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in 1964 and received his law degree from Yale in 1967.

While attending Yale in 1963, Mr. Lieberman became part of the first large group of Northern white students to travel south for the cause of civil rights, joining a caravan of more than 65 young people on a 1,300-mile trip from New Haven to Mississippi, where they encouraged Black residents there to register to vote, all while enduring harassment by white segregationists.

The episode became a rich part of his political biography during the 2000 campaign with Mr. Gore, and Mr. Gore referred to it in a statement on Wednesday evening, saying of Mr. Lieberman: “When he was about to travel to the South to join the civil rights movement in the 1960s, he wrote: ‘I am going because there is much work to be done. I am an American. And this is one nation, or it is nothing.’ Those are the words of a champion of civil rights and a true patriot, which is why I shared that quote when I announced Joe as my running mate.”

Mr. Lieberman’s marriage in 1965 to Betty Haas ended in divorce in 1982. That same year, he married Hadassah Freilich Tucker, a daughter of Holocaust survivors. He is survived by his wife; two children from his first marriage, Matthew and Rebecca Lieberman; a daughter from his second marriage, Hana Lieberman; a stepson from his second marriage, Ethan Tucker; two sisters, Rietta Miller and Ellen Lieberman; and 13 grandchildren.

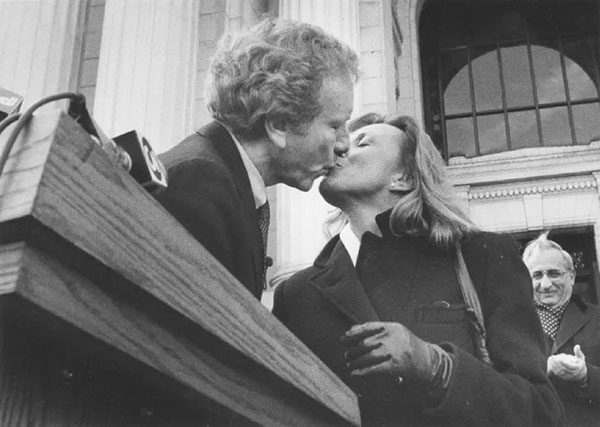

Mr. Lieberman with his wife, Hadassah, on the steps of the Connecticut Supreme Court

after announcing his candidacy for the U.S. Senate in February 1988.

After leaving the Senate in 2013, Mr. Lieberman moved to Riverdale and joined the Manhattan law firm Kasowitz, Benson, Torres & Friedman, which specialized in white-collar defense. Its clients included Mr. Trump during his years as a bankruptcy-troubled casino magnate.

In recent years Mr. Lieberman helped lead the bipartisan political organization No Labels as its founding chairman and recently as its co-chairman.

In 2017, Mr. Trump interviewed Mr. Lieberman for the position of F.B.I. director, to replace the fired James Comey, but Mr. Lieberman withdrew from consideration. He criticized Mr. Trump’s retreat from the Paris climate-change accords and his handling of the coronavirus pandemic. After Mr. Trump lost his 2020 re-election bid, Mr. Lieberman rejected the former president’s false claims that he had won.

In an interview with CNN weeks later, Mr. Lieberman denounced Mr. Trump as a threat to democracy. “Trump lost by seven million votes, and he’s hurting our democracy, and frankly hurting himself with this crazy business,” Mr. Lieberman said. “It’s a terrible thing he’s doing. There is no evidence of fraud.”

Remembrance by Matthew Lieberman ’89 LAW ’94

The Wall Street Journal

Matt Lieberman

April 10, 2024

Joe Lieberman Lived Life 110% to the End

He learned in 2018 that he had a serious disease. Even when he started feeling it, he kept working full tilt.

Matthew Lieberman

campaigning in 2020

My dad, Joe Lieberman, died two weeks ago. He fell and hit his head on March 26 and left us the following evening. The past two weeks have been a blur to me, like one long day, and I feel flattened.

Like everyone else, we in his immediate family have experienced his loss as sudden. But for us, it was a little less sudden than it was to so many who have shared this time of grief. We had recently learned that my dad had been diagnosed more than six years ago with a form of bone-marrow cancer called myelofibrosis.

Two years before that, he’d been diagnosed with a more chronic but generally not terminal condition called a myeloproliferative disorder. This is what we thought he still had. He would go to the doctor every year, hear that his blood tests were still good, and carry on. A friend reassured me that the sickness my dad had was the kind of thing you died with, not from.

But in late February of this year, we clearly came to understand that in January 2018, when he was almost 76, his diagnosis had officially changed to myelofibrosis. His life expectancy with myelofibrosis was probably not more than five years. Still, he never mentioned anything like cancer or a shorter life expectancy. He continued to live with his characteristic energy and positivity, so our concerns remained mild.

Things didn’t change until his final six weeks. The medicine he had been taking to manage the disease stopped working, and he became . . . sick. Why do I pause? Because he was still as productive and optimistic as ever. In late February, at a dinner for his 82nd birthday, he said he was feeling “really bad.” My dad wasn’t one to admit that he felt even a little bad. His words were alarming but belied by his upbeat demeanor. He was coming off a marathon of travel: a family celebration in Israel, the annual security conference in Munich, a business trip to Washington. He felt sick but sounded happy and was working full tilt. He agreed that at least until he felt better, he would travel less.

He went to the doctor at the end of February, when it was clear the myelofibrosis was taking a heavy toll. He let me talk to his doctor and report back to our immediate family. The doctor shared some troubling numbers. When I asked for a prognosis, he told me he wouldn’t answer directly because my dad himself hadn’t asked for a prognosis. He did say that he had seen patients at this stage live as much as a few years. At the same time, the doctor warned that if something went wrong, things could happen fast.

It seems likely that my dad’s fall and death stemmed from his advanced myelofibrosis. How or why doesn’t really matter. The basic facts are that he was well cared for, and that he’s now gone.

I share all of this for two reasons. First, we in the family were fortunate to have a month or so to wrap our minds around the idea that he wouldn’t be around forever. We had been told that things could happen quickly, but none of us expected the end this soon. Nonetheless, we had a month to brace ourselves, and I’m grateful for that.

Second, it isn’t clear my dad ever knew his life expectancy during his final six years. The same specialist treated him all that time, and my dad had never asked how long he had left. Instead, he kept moving forward, optimistic and strong. Did he have the willpower not to Google his condition and gauge his prognosis? Quite possibly. In any event, he lived as he had always lived right to the end. He fell that night in the den, hit his head, regained consciousness, got a glass of water and Tylenol for what he described as a normal headache, sat back down with his love, Hadassah, and shortly thereafter slumped in his seat. If he had any pain, it lasted no longer than a couple of minutes. It has helped us to hold on to this information, and perhaps it will comfort others who cared about him as well.

Do I wish that we had understood his condition better and longer? In retrospect, not really. My dad wasn’t about death; he was about life — and living it. If I had to guess, he knew he had a serious illness and may not have wanted to know more than that. If he’d known his life expectancy in 2018 and shared it with us, to a significant extent these past six-plus years would have been counted down. He would have been counting them down, and we would have been counting them down. That’s not how my dad lived, and that’s not how he would have wanted people to see him. Consequently, he lived life at 110% until the end.

As was the case all through his blessed 82 years, he did it his way. There’s nothing about Joe Lieberman’s life to mourn except that it’s over.

Funeral Service

March 29, 2024

Joe's funeral service was held at Congregation Agudath Sholom in Stamford CT, Joe's long-time home town. Distinguished speakers were Governor Ned Lamont of Connecticut, Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT), former Senator Chris Dodd (D-CT), and former Vice President Al Gore (D-TN), Joe’s running mate in the 2000 presidential election. Former Senator Bill Bradley (D-NJ) also attended. Eulogies were given by Joe’s daughter Hana, his stepson Rabbi Ethan Tucker, his daughter Rebecca, and his son Matthew.

Here is the video of the service, and below is a brief summary.

Summary of the Funeral Service

by the Associated Press

Former Vice President Al Gore and other politician dignitaries remembered the late Joe Lieberman Friday as a “mensch” who both bridged partisan political divides and wasn’t afraid to go against mainstream political currents, during a packed funeral service for the four-term U.S. senator.

Noting there is no English equivalent for the Yiddish term, Gore — who ran for the White House on a Democratic ticket with Lieberman in the 2000 election, making Lieberman the first Jewish candidate on a major party’s presidential ticket — told mourners at a synagogue in Stamford, Connecticut, that they could find its meaning just by looking at his former running mate, who passed away this week at 82.

“Those who seek its definition will not find it in dictionaries so much as they find it in the way Joe Lieberman lived his life: friendship over anger, reconciliation as a form of grace,” Gore said. “We can learn from Joe Lieberman’s life some critical lessons about how we might heal the rancor in our nation today.”

Top Connecticut Democrats, including Sens. Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy and Gov. Ned Lamont shared similar sentiments.

Lamont said his acquaintance with Lieberman started on “an inauspicious note” when they ran against each other for Senate in 2006. After Lamont defeated the incumbent Lieberman in the Democratic primary, Lieberman ran as an independent and won.

Lamont said Lieberman loved Frank Sinatra songs, especially “My Way.” “He did it his way,” Lamont said. “He never quite fit in that Republican or Democratic box. I think maybe in an odd way I helped liberate him because when he beat me — he beat me pretty good, by the way — he won as an independent.”

Lamont said Lieberman “was always a calming presence” and a “bridge over troubled waters as you see the partisan sniping from both directions.”

Blumenthal recalled Lieberman’s “tremendous accomplishments,” including helping to form the Department of Homeland Security and championing civil rights, voting rights, women’s reproductive freedom and LGBTQ rights. “But the greatest accomplishment of his life was his marriage to Hadassah and their children and grandchildren,” Blumenthal said.

Services were held at Congregation Agudath Sholom. Lieberman, a self-described observant Jew, once said, “I feel very lucky — my adherence to the Jewish tradition is really an asset. Religious Catholics and Protestants find a bond of common value with my beliefs and stand. It is this that makes me so proud of being an American.”

Lieberman’s youngest daughter, Hana Lowenstein, who moved to Israel in 2018 with her family, said tearfully that she had prayed, “Please God, give my father many more years. Let him see all of my kids’ bar mitzvahs, their weddings, his greatgrandchildren.” But she said God “had other plans.”

Lowenstein said that observing the Jewish Sabbath was “very dear” to her father and he would walk 5 miles in order to abide by the Sabbath prohibition on riding in a motor vehicle. “You were literally someone who was sanctifying God’s name by everything you did,” she said to her father.

Matthew Lieberman, his son from his first marriage, said his dad “was a blessing for all of us” but “a solid slice of people” nevertheless developed hatred for him. Despite that animosity, he said his father encouraged others to not let those disagreements devolve into hatred. “We’re not the Hatfields and McCoys here,” Matthew Lieberman said. “We’re Americans, we’re fellow citizens in the greatest country in the history of the world.”

President Joe Biden on Thursday called Lieberman a friend, someone who was “principled, steadfast and unafraid to stand up for what he thought was right. Joe believed in a shared purpose of serving something bigger than ourselves. He lived the values of his faith. …”

Published in the Yale Daily News

April 1, 2024

When Joe Lieberman ’64 LAW ’67 arrived at Yale College in the fall of 1960, he was eager to make his mark on the institution.

Lieberman, an observant Jew educated in Stamford public schools, was admitted to the University in an era of quotas designed to limit Jewish enrollment. During his undergraduate years, the future Connecticut senator would serve as chairman — now called editor-in-chief and president — of the News, gain entrance to the senior society Elihu, and forge relationships with Connecticut political leaders that allowed him to hand in a nearly 400-page biography of then-Democratic National Committee chair John Bailey as his year-long senior thesis.

Lieberman, 82, died on Wednesday.

Bob Kaiser ’64

“Joe felt himself to be kind of an outsider in that world, the son of a liquor-store owner, but he conquered,” said Robert Kaiser ’64, who served as the News’ features editor on the same managing board as Lieberman and later served as managing editor of The Washington Post.

A JFK Democrat

Kaiser met Lieberman in November 1960 when the two — then Yale first years — volunteered for the Connecticut Democratic Party to drive voters to the polls to elect President John F. Kennedy. Later, Kaiser encouraged Lieberman to join the News in the last of four “heeling” cycles — the process of becoming a News staffer, which was, at the time, a competitive process.

Paul Steiger ’64

“There was no real student government at Yale in those days and the News was, in many ways, the most prominent activity on campus,” said Paul Steiger ’64, who worked on the News with Lieberman and later founded the news site ProPublica. “Joe wanted to have impact and so he heeled and he was an outstanding heeler and then he was elected chairman of the News.”

Lieberman’s college roommate, Richard Sugarman ’66, a professor of religion who served as an advisor to presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in 2016, recalled that Lieberman wrote with “efficiency and speed” unlike anyone he had ever seen.

Kaiser remembered that he and Lieberman ran against each other for the position of chairman, and Lieberman received every vote but one — Kaiser’s own.

Howard Gillette ’64

Howard Gillette ’64, a managing editor for the News during Lieberman’s chairmanship, said that his near-unanimous selection distinguished him as an accepted leader among a class of highly accomplished News staffers.

According to Gillette, Lieberman’s involvement in campus leadership led him to Mississippi in the fall of 1963 with a group of News staffers organized by University Chaplain William Sloane Coffin Jr. ’49 DIV ’56 to participate in the civil-rights movement by campaigning for NAACP leader Aaron Henry.

Ahead of Mississippi’s 1963 gubernatorial election, Henry had organized the Freedom Vote Campaign, which rallied Black voters to participate in a mock election in which Henry was a candidate. The campaign’s goal was to combat disenfranchisement in the state by demonstrating Black voters’ desire and ability to vote.

In a column published in the News titled “Why I Go to Mississippi,” Lieberman wrote that while the mock election was, to him, “not the most exciting” civil-rights project, it represented an important effort to end the exclusion of Black Americans from elections.

“Our nation is emasculated as long as some of its rightful participants are excluded,” Lieberman wrote. “If I am able to carry across the concept of voting and the need for an all-out voter registration effort to 25 or 50 or perhaps 100 Negroes who have never been so confronted before, then I will return to New Haven with a sense of satisfaction. I go to Mississippi because I think this can be done.”

Lieberman’s Mississippi trip curiously resurfaced in 2006, when Connecticut State Treasurer Henry Parker questioned whether the trip — which the senator referenced in campaign speeches throughout his numerous electoral bids — had actually happened.

Stephen Bingham ’64

Gillette recalled that Lieberman’s campaign staff had contacted him about verifying that Lieberman had traveled to Mississippi. Gillette, who had not been on the trip, believed that Stephen Bingham ’64, a fellow News staffer who would later be tried and acquitted for suspected involvement in activist George Jackson’s escape from prison, would be the best source to confirm Lieberman’s participation.

Bingham told the News that he does not recall Lieberman going on his trip to the South — at least not in the initial group of around 20 Yale students who traveled and attended training together.

However, according to Gillette, the reason Lieberman may have missed the first days of the trip was to orchestrate an activist stunt at the News.

As Yale College made small steps toward loosening their policy on including women on campus — namely, allowing women into the Linonia and Brothers reading room, which was then a gentleman’s lounge — the News published on its front page: “Girls Continue to Flood Admissions Office With Applications.” The article announced a rally for the upcoming weekend — Parents’ Weekend — outside Woodbridge Hall and encouraged visiting mothers to join in solidarity with women seeking admission.

Jethro Lieberman ’64

According to Gillette, the women’s letter-writing campaign to admissions and the “boisterous” rally that followed were organized by Lieberman himself.

“It was the Civil-Rights Era — people were marching, people were doing these things,” Jethro Lieberman ’64, another News editor who had no relation to the senator, recalled. “Joe had been a public-high-school student in Stamford. This was the Kennedy years, and that’s just where most of us on the News were.”

Throughout his tenure, Lieberman used his platform as chairman to develop and express his political opinions through his editorials, many of which expressed support for the ongoing civil-rights movement.

Richard Sugarman ’66

Sugarman remembers that the only time he disagreed with Lieberman was when George Wallace, a pro-segregation governor of Alabama, was invited to speak at Yale in 1963. Lieberman defended Wallace’s right to free speech in a News editorial at the time.

“The principle of free communication in an academic community is sacred and inviolable,” Lieberman wrote in the editorial.

“Senator” at Yale

Lieberman was offered membership to Skull and Bones his senior year, but declined. Instead, he opted to join the Elihu Club, a senior society that eclipsed Bones as “cool and progressive,” according to Kaiser, who was also in Elihu.

His autobiographical presentation — known commonly as a bio, one of Yale senior societies’ most storied traditions — focused on his upbringing in a “Jewish liquor-store family,” the kind of background that was uncommon in the Yale circles Lieberman occupied, Kaiser said.

Jethro Lieberman, who was also in Elihu, recalled a society meeting where someone posed the question of what regrets each student thought they might have later in life, considering their intended career paths.

“Joe looked at us and said, ‘Well, you know, depending on how things go, it would really be terrible if I wound up as mayor in Stamford, and then got run over by a truck,’” Jethro Lieberman said. “From the earliest days, it was clear that he saw himself in politics and moving up the political ladder.”

At Yale, Lieberman’s nickname was “Senator,” Sugarman said.

Always a fan of elections, Lieberman ran for class secretary in his senior year. He came in second, instead becoming class treasurer.

First steps in politics

As a senior in college, Lieberman was a “scholar of the house.” The now-defunct academic program, which selected up to a dozen Yale seniors each year, allowed him to work on a year-long project of his choosing instead of taking classes.

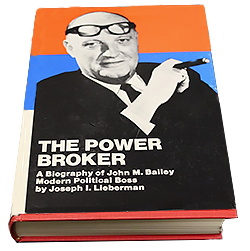

Lieberman chose to write a biography of John Bailey, the then-chairman of the DNC who dominated the state’s politics, for his senior project. He later turned his work into a nearly 400-page book called The Power Broker.

Michael Barone LAW ’69, Lieberman’s law school classmate who read the book, described it as “smartly objective and sometimes critical in a way that was really somewhat daring for someone with ambitions in Democratic politics in Connecticut.”

“He got a lot of mileage out of it,” Jethro Lieberman added.

Working on the book, Lieberman got to know many Connecticut Democrats, including former senator Abraham Ribicoff, who also served as Connecticut’s first and only Jewish governor. According to Jonathan Gruber, whose biographical film about Lieberman will premiere this year, Lieberman interned for Ribicoff in Washington during the summer of 1963 and saw him as a political role model.

Lieberman matriculated to Yale Law School immediately upon finishing college and started practicing law in New Haven after graduating in 1967.

In 1970, Lieberman, 27, successfully challenged incumbent State Senate President Ed Marcus in a Democratic primary. Lieberman spent the next ten years representing New Haven in the Connecticut State Senate, including six as Democratic Majority Leader.

“A lot of people in the Democratic Party weren’t so interested in having Lieberman go up against Marcus and so it was very hard for him to find volunteers,” Gruber said. “He went to the Yale Law School, and he found what he described as his ‘very affable fellow from Arkansas’ named Bill Clinton.”

Clinton LAW ’73 was one of several law-student volunteers on Lieberman’s underdog campaign. Twenty-one years later, Lieberman returned the favor, becoming the first Democratic senator to endorse Clinton’s presidential campaign, though he eventually became a fierce critic of the President during the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

In 1980, he left the State Senate to run for the U.S. House of Representatives in Connecticut’s 3rd district, which includes New Haven, but lost to Republican Lawrence DeNardis.

In 1982, he ran for Connecticut Attorney General. Gruber recalled that Matt Lieberman, Lieberman’s son, described the race as “make or break” for his father’s career. If Lieberman lost the race, he might have returned to law and forgone politics.

Lieberman won, and he held the position for six years.

Taking the national stage

In 1988, Lieberman — still Attorney General — ran against Republican Sen. Lowell Weicker, a popular figure among Democrats for his tough questioning of President Richard Nixon as a member of the Senate Watergate Committee.

“Lieberman was very much a longshot candidate,” Steiger remembered.

At the time, Steiger was a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, whose editorial pages leaned right. He recalled several conservative columnists endorsing Lieberman as Weicker increasingly voted against the Republican party line in Congress.

Meanwhile, Lieberman had garnered a favorable reputation for his record as a consumer advocate during his tenure as Attorney General.

One of Lieberman’s early supporters in the 1988 election was conservative writer William F. Buckley Jr. ’50, whom Lieberman had befriended at Yale through the News. Buckley created a political action committee, BUCKPAC, on Lieberman’s behalf, which sent donors bumper stickers with statements such as, “Does Lowell Weicker Make You Sick?” and “Republicans for Weicker? Yuck.”

Lieberman won the 1988 election by just 10,000 votes, upsetting the more liberal incumbent. He was reelected to the Senate three more times, including in 1994 with the largest-ever margin in a Connecticut Senate race and in 2006 as an independent after he lost the Democratic nomination.

In the Senate, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, Lieberman introduced legislation that led to the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. Senator Chris Murphy also credited his efforts to combat climate change for laying the groundwork for the 2022 passage of $369 billion in funding for climate and clean-energy programs.

As one of his last achievements in the Senate, Lieberman led a successful fight to repeal the “don’t ask, don’t tell” law, which banned openly queer people from serving in the military.

Former New Haven Mayor John DeStefano Jr. said that Lieberman had always been responsive to the needs of New Haven. He was a “local guy” in the city, DeStefano recalls, whom “you would see at Claire’s [Corner Copia].”

DeStefano said that when, in 2007, New Haven introduced the Elm City Resident Card for undocumented immigrants, the Department of Homeland Security started what he viewed as “retaliatory raids” in the city’s immigrant communities.

“Joe got the Secretary [of Homeland Security] on the phone to me the same day,” DeStefano said, adding that Lieberman helped stop the raids in the city. “That’s what Joe was really good at — responding to particular needs that affected people in their lives.”

In August 2000, Democratic presidential nominee Al Gore picked Lieberman as his running mate. The Gore-Lieberman ticket, which won the popular vote by over 500,000 votes, lost the general election to Republican President George W. Bush ’68 and Vice President Dick Cheney after a recount and Supreme Court challenge in the crucial swing state of Florida.

Lieberman’s selection made him the first Jewish American to run for vice president on a major-party ticket.

Throughout Lieberman’s political career, he maintained his Jewish observance.

Eden Migdal ’26, Lieberman’s granddaughter, recalled that Lieberman would walk home from the Senate with security personnel on Friday nights, declining to drive on Shabbat.

During his vice-presidential campaign, Lieberman made repeated assurances that he would be able to balance his observance of Jewish custom with the demands of the office.

Gruber said that Lieberman’s observance was a significant help in his many elections in Connecticut, making him an appealing candidate to Catholic voters.

“They appreciated a man of faith, even though it wasn’t their faith,” Gruber said.

In 2003, Lieberman announced his campaign for president. Running as a more conservative alternative to candidates Howard Dean ’71 and John Kerry ’66, the eventual nominee, Lieberman’s campaign announcement was attended by protesters from the group Jews Against Occupation, the News reported in 2003.

Emmaia Gelman, a member of Jews Against Occupation, a group that criticized Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and conduct toward Palestinians during the Second Intifada, was present at the protest. Gelman recalled her fellow organizers objected to Lieberman’s support of Israel, as well as the Iraq War.

“The Iraq War was absolutely important to us,” Gelman said.

A “stubbornly bipartisan” career

Throughout his career in the Senate, Lieberman made conservative friends and often reached across the aisle in his work.

He stood with his Democratic colleagues on domestic policy issues, like climate change, abortion rights, and gay rights, but departed from them on foreign policy.

In 2003, Lieberman, who consistently approved of American military interventions abroad, staunchly supported the Iraq War. He stood behind Bush as the president signed a resolution authorizing the invasion of Iraq.

However, by March of 2006, 59% of Americans — and 77% of Democrats — believed that the US should set a timeline for withdrawing most troops from Iraq by 2008, according to a CBS News poll.

Later that year, Lieberman explained that while he wanted to end the war quickly, leaving Iraq at that time would be a “disaster” prompting sectarian violence. He also continued to affirm the correctness of his vote to authorize the war.

When Ned Lamont SOM ’80, now the governor of Connecticut, launched his campaign to challenge Lieberman in the 2006 Senate race, he focused heavily on criticizing Lieberman’s record on the Iraq War and other cooperation with Republicans.

“If you’re not going to talk about this administration’s failed foreign policy, failed fiscal policy, failed environmental policy, and failed judicial policy, which are so harmful, then I will,” Lamont said at the time, blaming Lieberman for not being a “real Democrat.”

In the 2006 Democratic primary, Lieberman lost to Lamont by a 3.6% margin. Instead of dropping out of the race, Lieberman decided to run as an independent candidate.

Lieberman’s decision to run against a Democratic nominee angered some Democrats in the state, prompting them to launch an unsuccessful attempt to expel the senator from the Democratic Party’s list of registered voters. Senate Democratic leaders Harry Reid and Chuck Schumer also supported Lamont’s candidacy, citing Lieberman’s “closeness to Bush” as the reason for his primary loss.

The same year, Lieberman told The New York Times that his role as a senator required him to work with his colleagues on both sides of the aisle.

“I’ll tell you this: that doesn’t make me a bad Democrat, it makes me a better senator,” Lieberman told the Times.

In November, he won the general election with over 100,000 more votes than Lamont, becoming the first independent candidate to win a Senate seat in Connecticut since the emergence of the modern two-party system. Lieberman started his last term as a senator in January 2007 as an Independent caucusing with Democrats.

“When you have a long-term incumbent, the election really isn’t about party label or even about the opponent. It’s about whether people want to change or not,” DeStefano said. “I think it was a statement by the electorate saying, yeah, he’s doing a good job.”

Gruber speculated that Lieberman was blindsided by losing in the Democratic primary and that the loss contributed to his shift away from the party.

In 2008, Lieberman endorsed Republican John McCain, a long-time friend, in the presidential election and spoke at the Republican National Convention on McCain’s behalf. For some time, he even contemplated sharing the ticket as McCain’s running mate.

In 2009, Lieberman clashed with Democrats on the Affordable Care Act.

While Democrats debated President Barack Obama’s signature healthcare legislation, Lieberman came out in opposition to a government-run healthcare insurance option, or public option, even when its scope was reduced to Americans over the age of 55.

Rep. Rosa DeLauro, who represents New Haven, was a friend of Lieberman’s and endorsed his 2004 presidential campaign, which he cut short after disappointing results in early primaries. However, in 2009, when Lieberman opposed the public option, DeLauro called on him to step down from his Senate seat.

“I was angry at him and talked to him about it. We were dealing with potentially having a public option, and he came out in opposition to that,” DeLauro told the News. “I still believe it was the wrong policy. But I spoke to him and we have remained friends for many, many, many, many years.”

Lieberman eventually cast the 60th vote needed to pass the legislation, but his opposition to a public option forced Democrats to exclude it from the final bill.

By 2009, Lieberman had collected over $2 million in campaign contributions from medical professionals and insurers. The senator firmly denied that campaign finance influenced his vote.

Lieberman stepped down from public office in 2012 but remained politically engaged. In 2015, he became the founding chair of No Labels, a movement that aims to promote independent candidates for federal office. Recently, the group has gained prominence for its attempt to find an independent candidate to run in the 2024 presidential election. No Labels announced in early March that it intends to field a 2024 presidential ticket.

Kaiser remembered sending the senator a “stern email” expressing concern with Lieberman’s latest involvement in No Labels, which Kaiser believed would help former President Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, win in November.

“Like many others, he did not wrestle with the profound change that has occurred in the Republican Party in our lifetime,” Kaiser said. “He couldn’t cope with it intellectually or emotionally. The idea that Republicans had become the anti-government party was just too much for him to deal with.”

A legacy of “likable decency”

Lieberman figures prominently in Howard Gillette’s 2015 book Class Divides: Yale ’64 and the Complicated Legacy of the Sixties, which charts the formative convergence of the Kennedy presidency, the civil-rights movement, and the opportunity of a Yale education in the lives of Gillette’s classmates.

For Gillette, no member of the class of 1964 better exemplified a determination to reconcile the clashing perspectives that emerged from the ’60s than Lieberman.

“He found it troubling to end his political career outside the party of John Kennedy. For years he had been buoyed by the company of others he considered centrists like himself,” Gillette wrote in the book. “Like Ronald Reagan before him, Lieberman felt at the end of his career that he had not left the Democratic Party so much as it had left him.”

Jethro Lieberman also said that the Senator did not become more conservative over the years, but instead, labels changed.

Kaiser, on the other hand, believes that Lieberman’s views shifted dramatically over time. He said that Lieberman’s “departure” from the liberalism of his youth was exemplified by his support for McCain in 2008.

“Joe, in the early ’60s, was a Democrat and convinced liberal,” Kaiser said. “If I told Joe in 1962 that in 2008, he will be supporting a conservative super-hawk Republican president over the first Black American president, a liberal Democrat, he would not have believed it.”

Kaiser clashed with Lieberman over the years, occasionally approaching the senator about the policy choices that seemed so discordant with his past views. While Lieberman hated to be disagreed with, Kaiser recalled, he never got angry — an observation that Migdal also shared.

Upon his death, Lieberman’s political contemporaries, including Lamont, DeLauro, and Sen. Richard Blumenthal LAW ’73, released statements acknowledging their disagreements with the senator but affirming respect and gratitude for years of public service.

When asked by the News about Lieberman’s legacy, Kaiser, his college friend and longtime peer, emphasized his character over his policy accomplishments.

“Will he be remembered at all? Yes, he will,” Kaiser said. “Because he was the first Jewish candidate for vice president and because he was an extremely decent person whom everybody liked. He’ll be a symbol of likable decency that might survive for a while. But his contributions were temporal, temporary.”

The Yale College class of 1964 will celebrate its 60th reunion in May.

Letter from Yale’s Jewish Chaplain

A letter on the passing of Senator Joseph Lieberman

March 29, 2024

Dear beloved, dispersed members of Yale’s Jewish community,

With the passing of Sen. Joseph Lieberman on Wednesday, the United States and Yale’s Jewish community have lost one of our most principled and upstanding figures. In life, Senator Lieberman was a beacon of what can be accomplished, and what is worth striving for — and now we, individually and communally, share the blessing and obligation of carrying his memory forward in our memories and our actions.

Rabbi Jason Rubenstein

As a public figure, Senator Lieberman blazed a trail by reaching the highest echelons of American political life without sacrificing the quality or centrality of his Jewish life or identity. It is hard for many of the younger members of our community to remember the era of quotas in which Senator Lieberman grew up, or the ways that his public life as a visibly Jewish politician broke old norms and set new ones — and the difficulty of recalling that old time is a testament to his success in expanding the realm of the possible for American Jews.

The content of Senator Lieberman’s statesmanship, his personal integrity and dedication to working with those of different political parties and orientations, should forever remind and inspire us as to what is possible in politics. So different from today’s ascendant forces of polarization, Senator Lieberman understood deeply that politics begins, rather than ends, when we disagree with others — and is the art of weaving a nation, a political community, out of the threads of common humanity and shared values that are obscured by the forces and voices that would divide us. Here too, over the past generation, this humane style of non-tribal politics — even anti-tribal politics — has come to be seen in many quarters as some combination of impossible and unprincipled — and my hope is that we, and not only we, will take up the mantle of Senator Lieberman.

In addition to serving as a Senator from Connecticut for 24 years, Joseph Lieberman was also a devoted member of Yale’s Jewish community as an alumnus, a parent, and, most recently, a grandparent. He was a long-standing member of Slifka Center’s advisory board, an honorary co-chair of the capital campaign to renovate our building, and before the pandemic he headlined a Founders’ event at the Yale Club of New York — generously lending his name and time to our efforts to always build and rebuild this community on every level. That evening, he aptly quoted the Talmud’s characterization of the school of Hillel, who always articulated a sympathetic account of their opponents’ ideas, as a source of inspiration for his brand of politics. And last academic year, he responded enthusiastically to the invitation of an undergraduate leader to speak at Slifka over Shabbat, drawing a large and diverse audience. Whenever I was fortunate enough to share a conversation or podium with Senator Lieberman, I was always struck by his easy manner, his comfort with himself and those around him, and the uncomplicated sense of purpose he exuded.

In reflecting on Senator Lieberman’s life and legacy, I have returned again and again to Rabbi Judah the Prince’s proverb, “What is the path that a person should choose? One that is honorable in itself, and brings others to honor him.” Senator Lieberman was a man who did just that, choosing a path in life that spoke for itself, one that won him honor on the largest stages because so many others could recognize, together, across their differences, that his way was intrinsically honorable.

May we always carry his memory as a blessing, and may his family be comforted amongst the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem,

Rabbi Jason Rubenstein

Howard M. Holtzmann Jewish Chaplain at Yale

Remembrance by Edward Massey ’64

March 28, 2024

Edward Massey

Joe and I heeled the Yale Daily News together, he to become Chairman, me to become Business Manager. Along the way, as the two guiding forces of the News, we spent a lot of time together, drawing quite close. I began riding the train with him to Stamford on Friday afternoon to spend the weekend turning lights and stove on and off, walking to shul Saturday morning, and later learning that I held the honorable role of Shabazz Goy.

One day, at the end of our tenure, when all classmates were applying for important and prestigious graduate fellowships, I asked Joe: “Why don’t you apply for a Rhodes. You’re a shoe-in.”

“No, Ed, I don’t want to do that.”

“What do you want to do?”

“Go to law school. I want to get on with my career.”

And, boy, did he!

In the following years, like his relationship to the Class, we maintained a not close but good friendship. He even came to a Ravens game, volunteering the Rabbi who helped supervise the preparation of kosher food for that night’s invitation to all Kosher families.

In 2001 Joe walked to our mini-reunion in D.C. on a Friday evening. And left in time to walk home. Between the two, he told of his experience and aftermath as the first Jewish Vice-Presidential candidate.

“You know, I have crisscrossed the country three times since that election. I am amazed that we lost. As far as I can tell, everybody voted for us. … Except Massey.”

Six years later, I was so offended by how the Democrats had abandoned him and his honest integrity that, “While it won’t change my vote, I want to hold a fundraiser for you in Greenwich. Okay?”

“Okay.”

He won. He retired after that term. I honor his honest integrity, the calling card he used from his first term and throughout his entire life. I shall miss him.

Remembrance by Ward Wickwire ’64

March 29, 2024

Ward Wickwire

I knew Joe but post-graduation. He attended a mini-reunion in Washington just after Gore invited him to be his vice-presidential running mate in the presidential campaign. According to Joe, the press heard about Gore’s announcement before Joe and photographers showed up at his home while he was still getting breakfast coffee (and not fully dressed).

In 2014 at our 50th Reunion, I organized a panel discussion with Joe and John Ashcroft moderated by Bob Kaiser. Joe and John were Senators at the same time, both law school graduates (Joe from Yale and John from Univ. of Chicago), and both members of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Both very religious but one Jewish and the other Pentecostal Christian. One Democrat and the other Republican. Kaiser had been on Bradlee’s Watergate strategy panel and later the editor of the Washington Post.

The perception was that Joe and John were political opposites and not friends. The discussion at the Reunion dispelled that notion. In fact, according to John, they were friends. Also, I recall that they were each adept at working across the aisle. In fact, according to John, after the discussion Joe commented that, as retired senators, they could be a great consulting team. Unfortunately, that never happened.

John might be at our 60th reunion and I hope he will come. I’ll miss seeing Joe there. Too many of our senators or representatives lack the skillset of Joe and John. We’ll just have to struggle on ...

Remembrance by Bill Kridel ’64

April 1, 2024

Bill Kridel

Joseph I. Lieberman, Yale College 1964, was a gentleman, a Humanist, a Centrist, a Patriot, and a kind person whose sharp mind never got in the way of his wonderful, big heart and strong value beliefs. At Yale, he loved to debate political ideas and was a leader of The Party of the Left whilst his fellow classmate John Ashcroft was on the Right and I found myself in the Center.

Joe always had the national interest at heart and, although a Democrat, he never let party affiliation get in the way of what was best for America… sometimes to the great and public annoyance of his fellow Democrats who nonetheless respected him for his consistent espousal of smart and moderate views. Joe’s responsibilities in the Senate took him across many National Security subjects and many strong and powerful personalities, both inside and outside government, and yet he never swayed from his belief in a strong, prepared, and humane America ... and they respected and trusted him.

These principles stood him well most recently in his support of Israel in the aftermath of the October 7 attacks, massacres, and pillaging. He understood what it meant to be an ally and of what the true history in the Middle East was composed over a long, long period of time and not just since 1947.

Joe was also a fine counselor on how to deal with government agencies, especially those with sensitive missions. He will obviously be missed by friends, colleagues, family, classmates, and by our grateful nation for years of thoughtful, conscientious service and kindness. He most closely exemplifies the motto of another great American: Duty, Honor, and Country. We should all try to live up to his example and that mantra.

Essay, 60th Reunion Book

by Joe Lieberman

December 2023

[Joe submitted the following essay on December 21, 2023 for our 60th Reunion Book, to be published prior to our reunion in May 2024. On March 26, 2024, the day that reunion registration opened, he registered himself and Hadassah for the reunion. He died on the following day.]

Joe and Hadassah

at the Kennedy Center in 2009

At our 50th reunion, Hadassah and I walked into the Friday night reception with Bob and Hannah Kaiser. Bob looked around the tent and said “Who are all these old farts?” To paraphrase Pogo, a cartoon of our generation, “We have met the old farts, and they are us.” On the other hand, as another friend recently said to me, “We are in our bonus years.” Two years ago, as I approached my big birthday, I kept thinking “Oh my God. I am going to be 80.” When I got there, I found myself thinking “Thank God. I made it to 80!”

When I retired from the Senate early in 2013, someone sent me wise words of inspiration from a great Rabbi, Menachem Schneerson; The modern idea of retirement, he said, is based on a misunderstanding that there are productive and unproductive periods of life. It is true that as we age, there are some things we can’t do as well as we did when we were younger. But there are many other things we can do better because we have learned from experience. "There is a time to passively enjoy the fruits of one’s labor," the Rabbi concluded. "It is in the next world!"

In the years since, "in this world" I have been fortunate to be able to continue some of the work that was most important to me in elected office, and also to enjoy the extra time that this life chapter has provided to be with Hadassah and our family, to travel, and to write. I have worked in organizations that try to bring bipartisan problem-solving back into our national government, support a strong, principled foreign and defense policy, and sponsor school-choice options for lower-income children and their families. I have also had the opportunity through a part-time return to law practice, membership on a couple of corporate boards, and public speaking to provide more economic security for our family than I could during my years in public service.

I continue to look back at our time together at Yale College with great gratitude. Yale expanded my vision of what was possible for me in life and prepared me well to take those opportunities. And I made some wonderful friends who continue to enrich my life today. As the song goes, “Time and change shall naught avail to break the friendships formed at Yale.”

With all the political correctness, polarization, and bigotry on college campuses today, I am also grateful for how different and better our years at Yale were. There was much open debate and great tolerance of differing opinions and different backgrounds. I never experienced any anti-Semitism. Of course in our day, I must add, there were very few African Americans or Hispanic Americans, and no women. But over time, Yale has wonderfully eliminated those barriers.

The two Yale Presidents during our four years at Yale College, Whitney Griswold and Kingman Brewster, were national exemplars of the classic liberal education advocated by Griswold, and active principled citizenship under law championed and lived by Brewster. Together these two leaders set a high standard for civility and mutual respect in our little college community that I think has guided us throughout our lives.

And so, I thank Yale, and I thank God that we have made it to our 60th reunion and can look forward hopefully to our 65th!

Essay, 50th Reunion Book

by Joe Lieberman

May 2014

My four years at Yale College transformed my life and opened up opportunities for me that I don’t believe I otherwise would have had. I learned a lot from gifted professors and gifted fellow students. My sense of what was possible in my life expanded dramatically as a result of the lessons of history and culture I learned in the classrooms, the purpose and satisfaction I felt from getting involved in the social movements of our youth, such as civil rights, and the challenges, successes, and friendships that came along with chairing the Yale Daily News. I left Yale with much better skills and much bigger dreams than I had when I entered.

In the fifty years since then, I have had opportunities in our remarkably open country that go well beyond the dreams that were born in me at college. I was privileged to serve forty years in elective state and federal office and had the honor of running for Vice President in 2000. That’s one that went beyond my dreams. I am proud of what I was able to accomplish, and philosophical about the times I failed. Looking back at all the twists and turns of my political life, if I had it to do over again, I would happily make the same career choices. In January 2013, I left elective office as an unabashed believer in the imperative and honor of public service, appreciative of the unique opportunities it provides for a meaningful life.

Since leaving the Senate, my wonderful wife Hadassah and I have followed the migratory patterns of many grandparents. We moved to New York because three of our four children (the fourth is in Atlanta) and a bunch of grandchildren live here. We’ve really enjoyed seeing the family more regularly, and are feeling energized by being in a new place doing new things. I spend half of my work time at the law firm of Kasowitz, Benson, Torres & Friedman and the other half staying involved in public policy and public service in various ways.

I have a lot to be grateful for. I have been blessed, and I mean that quite literally because my faith in God has deepened and widened over the years. Reading over what I have written above, I realize I can sum it up in a variation of a familiar refrain from our college years: “Thank you God. Thank you Country. And thank you Yale.”

Essay, 25th Reunion Book

by Joe Lieberman

September 25, 1988

First, about Yale, I have the warmest feelings; maybe that's why I haven't yet left New Haven. Yale College was — well — a life-changing experience, opening my mind and eyes, broadening my sense of myself, and fixing my path to public service. The time at the Yale Daily News was particularly important, exciting, and expanding for me. My one major regret, as I look back (and I feel it often now when I see classmates) is that I didn't take the time to get to know more of my Yale classmates better, but there's still time. What an extraordinary group!

Looking back at the 25 years since college, I feel very fortunate. I've had my proportional share of slips and slides, disappointment and heartbreaks (most notably, the death of my father two and one-half years ago), but on balance, I've been lucky. I have four great kids, am very happily married, and have had some of the opportunities I dreamed of at college to make a difference in the life of my community through public service.

As I write this (on Sept. 25, 1988, on a plane to San Francisco for a fundraiser — for me), I'm a candidate for the U.S. Senate in a difficult but winnable race. If I win, the next stage of my life will be determined. If not, I'll still be Attorney General until 1990, but it fascinates me to say that I really cannot predict what I'll be doing in 10 years, if I'm lucky enough to still be alive. In other words, I've learned enough in these 25 years to eschew rigid personal agendas and to understand that life really does come in chapters only remotely connected to others, some we write and some that are definitely written for us.

Here are a few other things I've learned about myself and life in the last 25 years:

- Law and government are the way we decide our values, express our aspirations, try to make ourelves better and more civilized than we would otherwise be.

- Belief in God and observances of religion have enabled me to order my life and bring purpose and pleasure to my day.

- I receive much satisfaction from my work, but not as much as I do from my children.

- It's very important to eat wisely and exercise regularly (in my case, morning jogging).

- If you have a long day of work, you can revive yourself miraculously by changing your socks in the late afternoon.

- Most surprisingly of all, people who celebrate their 25th college reunion are still very young and vital!