In Memoriam

Bruce Warner

- Remembrance by Mimo Robinson, Bruce's widow

- Remembrance by Gerry Shea ’64

- Remembrance by Dick duPont ’64

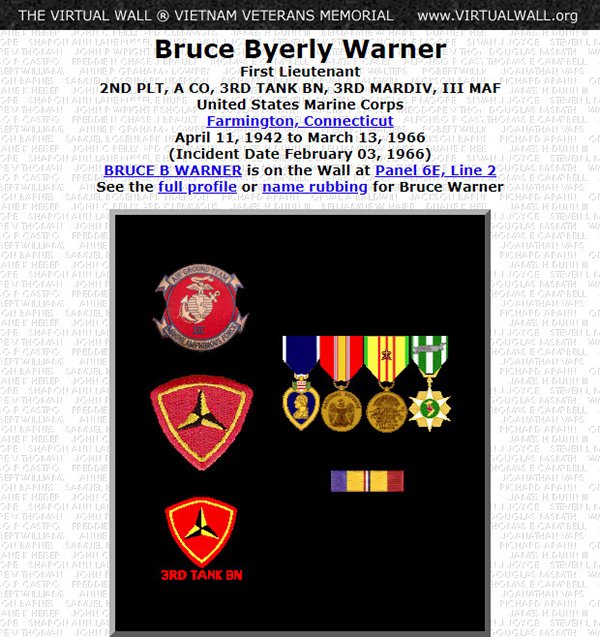

- Remembrance on virtual Vietnam wall

Bruce Warner

(1964 graduation

Bruce

by Mimo Robinson (the widow of Bruce Warner)

reprinted from our 25th Reunion Classbook

I was only 22 when I stood by the side of the road in that small town in Maine watching the parade go by, a parade commemorating all the young men who had died fighting for Uncle Sam. I was a widow. I had been married when I was twenty. He was my childhood sweetheart, a blond, blue-eyed, broad shouldered young man with his high ideals and grand expectations of teaching and coaching in his old school once he had "come to the aid of his country." We had needed to be together and had married as soon as he had graduated from college.

I watched the crusty old man, Ralph Cline, walk by, erect and tall, leading the parade in his World War I uniform, which 40 years later, still fit him just fine. Is that how Bruce would have felt in the year 2000, proudly sporting his jungle fatigues at the head of a parade? Would he then have had the unwavering belief in the necessity of that war as this old guy obviously had in his? After having lived through the heat, the filth, the deception, and the disillusion of a year in South Vietnam fighting a war for which no one seemed remotely grateful, it's difficult to imagine him feeling anything but hurt. But then, that is my disillusion, not his. I wasn't there...maybe there had been times of laughing and camaraderie and moments of heroism like on "Mash" that would overshadow the rest in future years. But I remember the letter that I got when he had only been there for two months telling me about the death of a good friend who had been at Quantico with us and I think of his pain. Fortunately though, while he was there, he felt pain, but amazingly, never seemed to question the cause.

Next in line after Ralph was the 4H Club, shiny young men and women with a firm understanding of the land, the birth of a calf, and how to produce alfalfa in Maine soil to feed their sheep. They looked so innocent.

My mind wandered back to the hospital at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines where I, as next of kin, had been sent by the Marine Corps to be with my beautiful young husband after he had been seriously wounded by a number of sniper's bullets during a late night volunteer mission. That body that had, during college, been so firm, so agile, that he'd been made captain of the baseball team, that body that had come to its maximum capacity for fitness during basic training at Quantico, Virginia, was now prone in a rotating hospital bed, pierced and torn, sewn together again, half strung up and half held down...and for what?

Ah, here comes the school band now in their green and white uniforms playing the tuba and the trombone. Do they know what they're playing? Do they know what "Anchors Aweigh" really means? And there's Mrs. Haskell, the story lady from the library. She must be seventy now, and there's the little Carey girl as Little Red Riding Hood...They're all there. Those wonderful stories where good triumphs over evil. When does that really happen?

I easily found myself back on the troop transport plane going toward Clark. I was scared and alone and the only one aboard this plane who was not a young soldier on his way into the rice paddies. Of course this plane was without benefit of movies, airplane snacks or a portable bar; it gave all the more time for gazing at a photograph of a girlfriend or fingering a rosary. They hesitantly asked me what I was doing there, although I'm sure, most already knew.

The parade had turned down the hill toward the water. This part had made me cry every Memorial Day, even when I knew nothing of war except what I had read in For Whom the Bell Tolls. I watched as Hugo Lettinen flew over in his sea plane and dropped a wreath on the water. Hugo was the one who was known to have had an intimate relationship with a woman on one of the islands here. He would fly out to see her in his plane. He apparently arrived one day unannounced and found her in bed with another man. He was said to have quietly gathered up all their clothes, left the house, gone back into the air and from the window of the plane strewn the clothes out over the harbor. Possibly it was with that same sense of revenge that he now threw the wreath from that same window. When it was floating on the water the uniformed men in the parade raised their rifles to their shoulders and fired three times.

The crack of the gunfire brought me back to Clark. Bruce's brother Aldy met me there. I don't think I could have made it through without him. We shared the hurt of watching one we loved in so much pain. We shared the knowledge that there was nothing that we could do to help. We also shared the estrangement that we felt from this person who had seen a whole section of life and death that we had never seen. We could walk the halls of the hospital together when Bruce was asleep and talk to the burn cases or help them write letters home. We could look in at the spinal cord injuries together, those who would never function by themselves again and feel lucky that Bruce's injuries were so "light." I felt so inadequate with my bedside gaiety or sadness; I felt so young and inexperienced in dealing with emotions such as these; I felt so robbed of the carefree joy of early marriage. Thank God that Aldy was there to smooth over my mistakes. I had been away from this young husband of mine more than I had been with him. He had been gone for eleven months. Our letters had been plentiful, but the lines of true communication couldn't withstand the reality of our very different worlds. He had written about Hue and DaNang and about his R&R in Hong Kong. He had written about friends and commanding officers and tanks and fears. I had written about work and friends and family and gatherings. We had needed to see each other to bridge the separation. But the long awaited reunion was clouded over by pain and sadness.

The parade was making its way back up the hill, away from the sea, toward the AmVets Hall where the final speeches would be given. At the end of the parade were the town's two recently polished fire engines from which a few volunteers in duty garb were throwing candy to the onlooking kids.

As I walked back up the hill I remembered walking outside St. Alban's Hospital on Long Island. Bruce had been discharged from Clark; he seemed to be progressing well and they were scared of infection. We all knew they also needed his bed. The family was elated with the news. Finally he would come home.

"Cardiac arrest in 302. Cardiac arrest in 302." Bruce died on March 13, 1966; his second kidney had failed. As Scott Davis, the young boy from down the street, played Taps on his bugle, I allowed myself to cry once more.

There have been other times through the years that I have cried about Bruce, but now, twenty years later, even more than crying, I would like to talk to him. Assuming that he, too, would have twenty years of perspective, I would like to know his thoughts and his feelings. I would like him to know my husband and my children. I would like to be able to sit down with him and, together, find peace.

December 9, 1985

Remembrance

by Gerald MacD. Shea

reprinted from our 35th Reunion Classbook

“Turtle Dove” was a song we sang in the days of gaudeamus. Long melancholy notes and words that stretched on for miles of farewells and depthless seas, in which a man who left for a while would roam ten thousand miles and promised to return but whose absence would be as long as it took the rocks to melt and the ocean to dry in the face of an eternal sun.

Also were those the days of Bruce Warner in the four-walled courtyard, Bruce who threw the ball higher and faster than any of us could. I still see his smile as he threw it to the roof. Sometimes it seemed we watched for a score of seconds before the ball came down. He would stand by the tree, arms folded, knowing exactly where it would fall, watching and smiling to see if anyone would catch it, would time it right and not forget the angle and speed at which he had thrown it, the angles of roof and gable and chimney it would strike.

But one day Bruce your key of life we so celebrated and held, the gold key, become Ky become death's wolf, as the ball soared up and up from a place called Jamaica where the cries for blood were in vain. Not all the blood in the world could have filled nor flowed through your veins of mesh. That ball I am sure is still rising, and I can see you smiling still, leaning against the tree. Oh, Mother of Men, have you grown strong in giving honor to, and have thy lights led, art thou rich in the toil of, those who designed that war of tet tet tet!? How proud are you, are they, of their deeds, of hundreds of thousands dead? Dim are those lights and thousands more, the friends of millions more. Cursed be your works of death, and woe to you who claim in lieu of deserved contumely our song to ring for you from our mother's breast. Did they throw the ball at Harkness too, the Bundys and Rostows and their companions, too dim to be led by thy light? O Mother of Men, whither thy lights have thee led?

Each day for years afterward I heard you calling "catch it, catch it, Shea, see if you can catch it!" Late at night the only sounds I heard were the occasional sirens, low-pitched sirens it seemed, and the howling of a dog somewhere below ― or was it a wolf ― forty stories below. How simple the life of that hound, to whine at the sounds of sirens. Or perhaps it mourns for you and the ball that will never fall, the sirens heard too late, the arteries too broken open to hold your oceans of blood.

But the blood of our affection shall never run dry nor the rock of our remembrance melt with the sun. Fare ye well, my Bruce, we must be gone, and leave you for a while, we can be there to catch you but for a time. We'll come back again, though we roam ten thousand miles, though we roam ten thousand miles.

Letter to Mimo

from Dick duPont ’64

February 4, 2022

Hello Mimo and David:

I never had the pleasure of meeting you, so I’m writing this letter now as a means of introducing myself. I hope I am not imposing. Sam Crocker, my venerable teammate from Taft and Yale, found me this address. I hope it reaches.

Though Bruce and I weren’t super-close friends, our relationship was always enthusiastic and cordial. We became fond of each other and always made sure to say howdy and chat a bit at the countless after-game Taft and Hotchkiss “teas” (a civilized custom which I trust still happens despite the presence of woke and absence of tea). Not many of us developed friendships in that way, but a few did — and those friendships were often long-lasting. Bruce and I just continued right into the “Whale” and never broke stride — a joy to be playing on the same team at last.

Just after sophomore muster, I made the decision to leave Yale and pursue my aviation ambitions. That was a tough decision on its own, but even more so from a hockey perspective. I particularly enjoyed playing with Sam Crocker. “We had great communication on the ice,” to quote Sam — mainly because we had been linemates for all four years at Taft plus our freshman year at Yale. I hated to break our tradition, but that’s the path I chose. Because of that, my contact with Bruce faded over the years. Then one day, quite some time after Vietnam, Sam told me Bruce had perished in that war. I was stunned, and I was truly sickened to hear that news. Bruce of all people — how could that possibly be? I still feel bitterness and disgust.

Recently, when Tony Lavely posted his email to the Yale Class of 1964, I discovered for the first time the Yale In Memoriam link at the bottom. I went straight to Bruce’s name. There I found your beautifully written remembrance, Mimo — poignant and direct, and, I dare say, as germane now as ever. Later, Sam also sent me David’s poem, “For Bruce,” which I loved. David, delightfully simple in form, your poem is powerfully evocative from many angles — a series of touching vignettes woven together by the spirit of a fine young man — really remarkable, What a pair you must be, for you both shared your lives with Bruce before and after his death. Finding your way together after that had to be as challenging as it was rewarding.

Lately I’ve been creating booklets using Microsoft Office Publisher (long on images — mercifully short on text). I send these to my family and friends, in this case Sam Crocker, Patrick Caviness, and my new friend, Tony Lavely. Quite coincidentally, it contains a few words about Bruce. It also speaks a bit about life after the four-score divide with some thoughts about the loss of friends and family. I have enclosed a copy for you two.

Sincerely,

Dick