Class News

Howard Gillette '64: Final lecture at Rutgers

Howard Gillette, delivering the Miller Lecture

at Rutgers-Camden on May 5, 2011

Howard Gillette '64 delivered the Fredric M. Miller Memorial Lecture on May 5, 2011, on the occasion of his retirement from Rutgers-Camden, where he had served as Professor of History since 1999. Howard was the founding director of MARCH, the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities. The annual Miller Lecture recognizes the late Fred Miller's pioneering work as an archivist and public historian to preserve and promote the history of Philadelphia, where he directed the Urban Archives at Temple University; and of Washington, D.C., where he worked at the National Archives and Records Administration.

Here is a slightly edited version of Howard's lecture.

Between Justice and History: This Year's Fredric M. Miller Memorial Lecture

MARCH director Charlene Mires had the good sense to ask me to do this lecture on a day that stands out in our region, December 15, 2010. A number of people in the room will remember well sitting in the bitter cold that day as, after many years of contentious debate, the President's House memorial was dedicated at Sixth and Market streets in Philadelphia. Headlines the next day in New York as well as Philadelphia confirmed the importance of the moment: Philadelphia was standing tall, at once contemplating a difficult past and anticipating a bright future. Yes, Philadelphia at that moment could well have fulfilled the city's late visionary planner Edmund Bacon's representation of the city as the giant of Megalopolis, the extraordinary urban corridor running from Washington, D.C., to Boston, where so much of American history has been forged. Although Charlene was scarcely aware of it at the time, December 15 was also the day that pitcher Cliff Lee re-signed with the Phillies. Fred Miller would very much have appreciated the convergence of events that day.

The opening of the President's House memorial on

Independence Mall, Philadelphia, on December 15, 2010,

culminated years of sometimes contentious discussion

about how to interpret this site.

When I asked Charlene what she thought of the final product at the

President's House, an open-air installation marking the site where both

presidents George Washington and John Adams lived when Philadelphia was

the nation's capital, she replied, "At least it's a victory for social

justice." As a member of the oversight committee to the memorial,

Charlene knew all too well the difficulties in attempting to commemorate

both the crystallization of executive power and the presence of slaves

in Washington's household and his efforts to thwart their freedom. Over

time, as project personnel changed, details debated, and concepts tried

and then discarded, much of the clarity that had initially made this

such a compelling public investment dimmed. The product unveiled

December 15 was not perfect history. It didn't do full justice to the

full importance of what took place there, but it did, against

considerable odds and with the incredible support of citizen

organizations such as Avenging the Ancestors Coalition as well as

historians and government officials, assure a complex and more just

picture of our origins as a nation.

Slavery could be recognized publicly and inescapably now, not just as

incidental to our founding, but as integral to the forging of American

identity. Freedom and unfreedom were, as the Miller Lecture's first

speaker historian Gary Nash put it, "braided together."

In retrospect, I have to say that discussions about the President's

House were some of the most elevating and informative exchanges of my

professional career. That fact notwithstanding, it is impossible to

ignore the considerable challenges the project posed to professional

historians, public officials, and citizens of all backgrounds and

beliefs. The expectation that the best historical insights into a

subject as difficult as slavery could translate into a public memorial

that would have lasting social as well as educational value did not

necessarily mean they would adequately serve those noble purposes.

Like any historical product, the President's House has already begun to

draw its share of criticism, none more stinging than architectural

historian Michael Lewis's review in a recent issue of Commentary.

Lewis makes some telling points about the awkward siting of the

structure relative to the original and the imbalance of the

interpretation — giving more attention to how Washington treated his

slaves than a full treatment of the nation-building that took place

there under the direction of two presidents. Echoing an earlier charge

by New York Times museum critic Edward Rothstein that the

memorial had made history subservient to identity politics, Lewis goes a

step further to claim that the whole effort served as Gary Nash's

revenge for the harsh political reaction he received in the mid-1990s as

head of the effort to devise national standards for teaching American

history. "Honorable in its intention but misguided in execution," Lewis

asserts, the memorial should be dismantled and the site rebuilt.

[1]

Lewis goes too far in his comments. As anyone in the field understands,

history, like the law, is subject to revision and reinterpretation. When

those of us who had joined together as an ad hoc group of

historians to promote this effort received the "final" text for the

memorial, we were surprised at the number of omissions and errors that

threatened to make their way into the exhibit. While a number of issues

were dealt with at the time, the larger point is that even then we spoke

about devising new interpretive panels and developing educational

programs that would flesh out the story at the site, a process that is

bound to take place over time. To give the memorial its due, however,

one only need compare it to previous memorials to slavery and its

abolition.

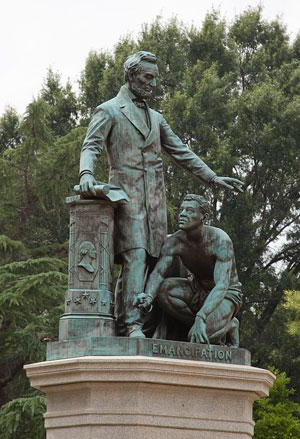

Emancipation Memorial by Thomas Bell, erected in

Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., in 1876. Contributions

of freed slaves funded the monument; the last person

to be captured under the Fugitive Slave Act, Archer

Alexander, was the model for the freed slave.

The first such monument, sometimes referred to as the Lincoln Memorial

before the more famous memorial was built on the Mall in Washington,

D.C., is sited in Lincoln Park in Washington's Capitol Hill

neighborhood. Completed in 1876, just as Reconstruction was coming to an

end, the monument depicted an ex-slave crouching shirtless and shackled

at the feet of the "Great Emancipator." Grounded in the immediate

post-war Republican embrace of emancipation, the statue conveys a

contradictory message, at once celebrating freedom for African Americans

but casting the freedman in a servile position, denying him his own

agency.

At least he was part of the picture. A generation later he had virtually

disappeared in the more famous and centrally sited Lincoln Memorial.

Whatever enlightened efforts we now associate with the memorial

following Marian Anderson's famous 1939 concert there after the

Daughters of the American Revolution refused to host her performance at

Constitution Hall and Martin Luther King's 1963 "I have a dream" speech

during the historic March on Washington, it cannot be denied that this

new memorial, constructed in 1922, replaced the freedman with the Union

as Lincoln's primary beneficiary. It did so by depicting each state

grandly in columns equally responsible for upholding the edifice of the

nation. For those familiar with David Blight's Race and Reunion: The

Civil War in American Memory, the cultural roots of the Lincoln

Memorial are obvious: a national memory that reconceived the Civil War

as mutually heroic on both sides while obliterating any implication that

slavery proved the anvil on which war was forged and emancipation and

the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S.

Constitution that followed the affirmations of a just cause brought to

conclusion. [2]

The great accomplishment of the President's House is that it faces

directly the contradiction at the heart of the grand American narrative.

While that might be expected at a time when we commemorate the

sesquicentennial of the Civil War, evidence abounds of the still

distorted lens through which such a traumatic, yet formative experience

is treated: a gala secession ball in Charleston, South Carolina, marking

the anniversary of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, the current

governor of Mississippi speaking about the benign intentions of the

White Citizens Councils when he was growing up in the 1960s, even Robert

Redford's film The Conspirator papering over the role of slavery

in sectional division.

While future generations are bound to look back critically on the

President's House as the product of a particular time and place, that

fact shouldn't diminish its contribution. As Steven Conn puts it so

nicely in his review in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and

Biography: "With the President's House . . . we were all reminded

that there is a much larger public that cares deeply about the past,

feels connected to it, and in this case made its voice felt."

[3] Such rewards as might be garnered from the

engagement of difficult issues in an inclusive manner provide the

subject of the remainder of tonight's presentation.

There's no better place to suggest the challenges historians face in

fully discerning the nature of past injustices than the work I did with

Fred Miller on the 1995 book Washington Seen. [4]

I was well along in my own book on the history of Washington, Between

Justice and Beauty, [5] from which I have

drawn my title tonight, when Fred approached me about collaborating with

him. His idea was to follow the format of the two ground-breaking

photographic histories he had done on Philadelphia with Allen Davis and

Morris Vogel. [6] He had already started the photo

research. Presumably I would bear much of the burden of writing the

accompanying text. What could be easier? I discovered quickly, however,

that photographs could be troublesome, telling stories that challenged

my best understanding of the city and its history.

De facto racial segregation on a D.C. transit bus, 1932.

It was well understood by historians of Washington at the time that

radical Republicans had used federal control of the city to test its

approach to Reconstruction in the South after the Civil War. Thanks to

their efforts, public transportation was desegregated. Their

accomplishment survived into the twentieth century, even as laws

assuring access to other public accommodations were uniformly and

persistently ignored. So we believed, but that judgment was tested by a

photograph dredged up from the Federal Signal Corps, in Fred's typical

fashion of leaving absolutely no stone unturned. The image, which he

determined had been taken at the time of the Bonus Army protest on the

Mall in 1932, showed a federal officer looking for protesters who might

be riding on a D.C. transit bus. Here we were: confronted with the fact

that every black person was sitting "at the back of the bus." How could

this have been so when we had other evidence beyond received wisdom that

blacks and whites were mixing as they used public transportation on a

daily basis?

Through his research Fred tracked the streetcar route, helping craft the

final caption, which read: "This streetcar had come from the far

southeast, passing through the white Congress Heights area and then the

black Barry Farms and old Anacostia areas on the way to Eleventh and

Monroe Streets, NW. It is likely that the whites boarded first and

naturally took the front seats, while black passengers then took the

seats in the rear rather than sitting in vacant places next to whites."

[7] That was what appeared in print, but the

photographic evidence bothered me, and a subsequent interview suggested

why.

After several calls to long-time black residents, I was fortunate to

uncover a story that suggested an alternative explanation. My informant

told the story of a dapper black man well known to have ridden District

buses in his Sunday best even in the middle of the week. One day he

chose to sit next to a white woman at the front of the bus. When the

lady got up right away to take another seat, this gentleman took a

florid handkerchief from his breast pocket, waved it grandly so no one

on the bus could possibly miss the gesture, and proceeded to wipe the

vacated seat next to him. Here was clear evidence that while the law did

not prescribe separate seating, social custom did. How pervasive that

practice was over what period of time remained elusive, of course, but

the larger lesson was brought home, that a fair reading of the past

demands interrogation beyond traditional sources and on both sides of

the race divide.

But mining all sources for as accurate an understanding of the past as

possible is not the only challenge to public work when addressing

America's complicated racial history. Consider the case of my former

colleague at George Washington, John Vlach. Boosted by the success of

his book on the material culture of slavery, Back of the Big House,

[8] the Library of Congress invited John to curate

a traveling exhibit by the same name. After drawing appreciative

audiences at several stops in the South, the exhibit returned to

Washington, where it was mounted at the Library of Congress itself in

December 1995. Its exhibition there was very short. Following the

complaints of a number of black employees, the library summarily removed

the exhibit. John was crushed, and sensing a story I called a friend at

the Washington Post. The story appeared the next day on page 1,

and John's phone began ringing off the hook as wire services and even

PBS picked it up. [9] With the press

investigating, it became apparent what had happened. Black employees,

locked in a grievance procedure with the library over back pay and

commonly using the term "big house" to refer to the library

administration, were not about to accept an exhibit that reminded them

of what they perceived to be an enduring legacy of racism in their own

work lives.

The positive result of the mass of publicity that followed the exhibit's

closure was that the city's central public library, named for Martin

Luther King, volunteered to host the show at its facility. Two weeks

later the exhibit reopened with a program drawing a large and racially

mixed audience. When I spoke with him recently, Vlach revealed how

nervous he had been as his introduction on the program neared. Despite a

distinguished career that involved deep and mutually respectful

relations with the African American subjects of his research, he was not

confident that this was the moment when Washington's notorious racial

divide would be bridged. Following John's remarks a distinguished black

man sitting in the first row rose to make the first comment. He turned

out to be a federal judge, and thanking John and the library heartily

for bringing the exhibit to the city, he immediately broke the ice. A

robust discussion followed, involving not just the depiction of slavery

but its long reach over time. Conversations continued as the crowd of

some three hundred people broke to see the exhibit for themselves. This

was a fitting prelude to the marvelously rich set of public

conversations about slavery that took place at the archaeological site

of the President's House several summers ago. And yet, such experiences

must be recognized for what they are: the exceptions in a pattern of

racial discourse that lacks common points of reference and

understanding.

It was my appreciation for both the difficulties in addressing

unresolved issues of social justice and the challenge of making any such

efforts broadly inclusive that most informed my view of how to meet the

National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) challenge grant to form a

regional humanities center shortly after my arrival at Rutgers in 1999.

Of course, these were not our only or even most overt goals as we moved

successfully through two rounds of competition for funding and, in 2000,

became the NEH's Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities

(MARCH). By the time the President's House controversy emerged, however,

MARCH could easily envision it as an exemplary teachable moment for the

city, the region, and the country. Our 2003 public conference, "Beyond

the Liberty Bell," sought to institutionalize the high level of

engagement and accountability that was characterizing reassessment of

the presentation of slavery at Independence National Historical Park.

Our intent was to forge in subsequent meetings and Web-based exchanges a

collaborative process with area cultural institutions aimed at

developing, through discovery, collaboration, and exchange, a deeper,

richer, more inclusive view of our region's heritage, and in the

process, to make Philadelphia's story more than the sum of its parts. As

so often happens, a potential funder didn't see it our way, explaining

that its board did not believe that such work could be executed

successfully from a university setting. That left us more to prove, of

course. Despite that setback, the President's House memorial

materialized. In the process other related benefits accrued from MARCH's

efforts to stimulate public discussions about the region's history,

including the introduction of the story of slavery at Cliveden, the

Germantown, Pennsylvania, home of the prominent Chew family; a much

invigorated History Day program in Philadelphia; and the African

American Museum in Philadelphia's new permanent exhibit, "Audacious

Freedom: African Americans in Philadelphia, 1776-1876."

The President's House controversy might not have been so difficult had

we not entered a complex post-civil rights era, where social justice no

longer meant overcoming overt forms of segregation. For my part, I

perceived racial division as very much alive in Camden, New Jersey, as

the city struggled to overcome not only the deprivations of

disinvestment but the stigma attached to the visible effects of high

poverty and racial isolation. To counter that isolation, I was

determined from the start to conduct my research and writing on the

city's history in a public manner. The formation of a regional

humanities center helped support that goal. Under the terms of the NEH

challenge grant, we were required in the final round of competition to

launch three conferences. I choose to feature in one of them the effect

of economic decline on Camden's civic assets. During the first part of

the conference, long-time residents fondly remembered Old Camden,

telling multiple stories of how working people living in ethnically

distinct neighborhoods utilized high levels of social capital to sustain

their families and advance the prospects for mobility for the next

generation. The panel addressing Camden after its "fall" pointed to a

host of organizations and activities that filled the gap when the old

ethnic neighborhoods dispersed along with viable employment options. It

was a stimulating and informative discussion, which we were able to

extend by contracting with the newly formed youth development

organization, Hope Works ‘N Camden, to create a Web site taking up the

subject of community building over time.

A major feature of that site was the opportunity for visitors to record

memories of their own neighborhood experiences. Submissions, as might be

expected, contained a good deal of nostalgia for the days before the

city's decline, but there were also some surprising testimonials from

those who had weathered some of the city's worst storms during the

post-industrial era. I remember particularly a call I got from Seattle

from a man in his forties who had seen the site and urged me to let him

know if I could find a way to get him positively involved in the city. I

was surprised later on to read his own message on the site about growing

up with drugs in the city. Clearly he had left Camden to preserve his

future, and yet, remarkably, exposure to this dialogue about the city's

past was enough to prompt him to consider returning home. I experienced

frequently that interest in the city's well-being among ex-residents,

and I could see it materializing in a variety of forms: through their

support for faith-based community development corporations, through

volunteer activity, and through the creation of new partner

organizations. Many of these organizations not only appeared in my book

but were featured at the conference we hosted in 2005 to note its

publication. [10] That same day we launched the

Invincible Cities Web site

featuring the photographs Camilo Jose Vergara has taken in Camden over

the past quarter century. The site has since expanded to include

Richmond, California, and New York's Harlem and has been featured on the

programs of major national conferences and at Vergara's speaking

engagements, including at Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania,

Columbia, and the University of California, Berkeley. In this way, we've

both fostered dialogue within the city and extended Camden's story

nationally and internationally.

It would be naive to claim that historically grounded dialogue alone can

establish common ground among contending parties and break the many

impasses that prevent full utilization of the cultural resources in

their communities. I would argue, however, that such dialogue pursued

publicly and with every effort at inclusion is a necessary starting

point. Even disappointing results have their value. The effort to

preserve and interpret the Bethlehem Steel site in Bethlehem,

Pennsylvania, is a case in point. MARCH entered the discussion of how

best to reuse the massive site after the company shut down in 1998. Save

Our Steel organizers Amy Senape and Mike Kramer had already taken the

lead with some passionate partners to make sure there was a site still

to be saved. As he received encouragement from other mayors as well as

the national, state, and local communities, Bethlehem mayor John

Callahan shifted his intent from complete demolition on the 1200-acre

site towards a plan for reuse. However, it took Shan Holt's leadership

as MARCH's director of programs to see the importance of bringing

different stakeholders together to forge a common vision for the site.

In March 2004 we did that through a full day's workshop, which included

members of the mayor's staff, focusing on what the historic core of the

site could be. Within a year, participants had formed the Lehigh Valley

Industrial Heritage Coalition. A planning grant from the NEH allowed

MARCH to support two days of public meetings resulting in a working

concept for making the core historic area the hub not just for

interpreting steelmaking but for directing visitors to a range of

historic sites in the region.

Former steel worker Bruce Ward gives participants

in MARCH's May 2007 Bethlehem conference a tour

of Bethlehem Steel's welfare building, where

workers changed clothes before going out on

assignment and then back into street clothes upon

leaving for home.

Of course, it is a long way from conception to execution. Not unlike the

President's House controversy, stakeholders embraced different visions

for the site. Here the primary tension stemmed from long-held

differences between capital and labor. Despite MARCH's intervention, the

nonprofit organizations and their university allies found it difficult

to forge agreement with the primary owner of the historic core, the

Sands Casino, and its preferred cultural partner, the National

Industrial Museum, which the steel company formed to advance its own

understanding of the site and its significance within the larger history

of technological development. Despite considerable time and money

invested in its support, the industrial heritage coalition failed to

take hold fully of the project. The effort to promote history that

acknowledges the full range of activity on the site — one that tells the

story of workers and their families as well as the technology of steel

making — continues, with able hands seeking resources to assure that an

inclusive vision governs reuse of the site. [11]

But the early successes have gone to the profit makers and power

brokers, not the nonprofits. At best, the vision for sustained and

honest interpretation at the steel site remains a work in progress. The

record of our efforts has nonetheless become the staple of the

Rutgers-Camden public history classes, and I hope other public history

programs will pick up this important case study as details of the effort

become better known. [12]

Three years ago, we launched yet another major effort informed by

principles honed in MARCH's earlier projects: an encyclopedia of Greater

Philadelphia (http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org

). The particular cast of this effort owes much to the President's House

campaign, suggesting yet another secondary benefit from that effort.

Beyond the important purpose of compiling information, this project

embraces an approach and set of goals that set it apart from earlier

city encyclopedias, including the admirable volumes generated for New

York and Chicago. [13] It has been a collaborative

effort, gathering knowledge not just from scholars based in universities

but from a host of institutions that have been collecting and generating

historical information about the city. Just as we had for the

President's House and the Bethlehem projects, MARCH crafted workshops to

envision how information might be generated and how its compilation

would aid participating organizations, which ranged from historical

societies and museums to policy organizations such as the Economy League

of Greater Philadelphia and the Fels Institute for Public Policy at the

University of Pennsylvania. The plan for the encyclopedia has evolved

toward the concept of an online information gateway for the region that

includes a number of forms from online entries to the curation of

monographs, lesson plans, and tour guides. A print version also remains

under discussion.

Most central in my view is that the encyclopedia would help users of the

information place themselves in both time and space within this vibrant

yet widely fragmented region. Here Neil Peirce's contention is

convincing, that regions are the keystones to the world economy and

thrive only as much as each of their constituent elements does well.

[14] The presence of poor or socially isolated

neighborhoods and cities at the heart of a region adversely affects the

whole. The encyclopedia can be seen as a catalyst for advancing mutual

understanding of the region's constituent parts through the exploration

of the web of beliefs and relationships that have helped keep us divided

by race and place over time. To the degree that this process of shared

community knowledge is robust and inclusive, it can build public

interest and support for policy actions to advance greater measures of

equity, such as affordable housing in asset-rich jurisdictions for those

otherwise confined to asset-poor inner city and older suburban areas.

The encyclopedia is thus understood as a civic investment as well as a

source of continuing education. I am pleased that Charlene Mires, who

first conceived the project and has brought it to Rutgers, continues to

make the encyclopedia a primary demonstration project.

Rutgers-Camden has proved a wonderful place to pursue these projects. I

am especially proud of MARCH's four Clemente program classes that

brought Camden area adults without the benefit of higher education

together in twenty-six weeks of American history instruction.

[15] These classes, intended to prepare students

for college entry, addressed with powerful effect just those difficult

issues of American freedom and unfreedom we have discussed tonight.

Plans for future Clemente courses are on hold, but in the meantime we

have introduced a course to the college curriculum on Camden history,

politics, and development, which brings leading regional figures into

the classroom and encourages and prepares students to take an active

role in their host city. I am delighted that the college's director for

civic engagement, Andrew Seligsohn, has taken over the course from my

inaugural effort a year ago. His work and that of other colleagues to

advance the university's engagement with the city and region is very

much in line with my hopes for MARCH and the college when I first

arrived twelve years ago.

It has been my great privilege to have been a student of this city

during this past decade and a partner in this wonderful institution; and

to have had my chance to explore further the issues that had animated my

career before I arrived here. The challenges at Rutgers-Camden are

significant, but there is considerable determination to capture the

great assets of the institution and turn them to just purposes, not only

for Camden but, as befits a great university, for broader use and

dissemination. When they were created early in this century, the

regional humanities centers were granted considerable leeway to chart

their own direction. I am pleased that MARCH could successfully combine

commitments to social justice and public history. In examining difficult

issues from the past, we have forged new partnerships as part of a

vision for attaining a more perfect future. I am confident that effort

continues in able hands and that the effort will build in the years

ahead.

[1] Michael J. Lewis, "Trashing the President's House: How a great

American discovery was turned into an ideological Disgrace,"

Commentary, April 2011, 5. Edward Rothstein, "To Each His Own

Museum, as Identity Goes on Display," New York Times, December

28, 2010.

[2] David Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

[3] Steven Conn, "Exhibit Review: Our House? The President's House at

Independence National Historical Park," Pennsylvania Magazine of

History and Biography 135 (April 2011): 196.

[4] Fredric M. Miller and Howard Gillette, Jr., Washington Seen: A

Photographic History, 1875-1965 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1995).

[5] Howard Gillette, Jr., Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning,

and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C., (Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

[6] Fredric M. Miller, Morris J. Vogel, and Allen F. Davis, Still

Philadelphia: A Photographic History, 1890 — 1940 (Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1983) and Morris Vogel, Fredric Miller, and

Allen Davis, Philadelphia Stories: A Photographic History, 1920 —

1960 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988).

[7] Miller and Gillette, Washington Seen, 128.

[8] John Vlatch, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of

Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1993).

[9] Mark Fischer, "Library of Congress Scraps Plantation Life Exhibit,"

Washington Post, December 21, 1995; Editorial, "Liberty on

Tiptoe," Ibid., December 22, 1995; Charlayne Hunter-Gault,

"Picturing Slavery," The News Hour, February 5, 1996.

[10] Howard Gillette, Jr., Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal

in a Post-Industrial City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2005.

[11] A primary repository of material for a larger understanding of the

Steel and its influence has been compiled on the web site Beyond Steel,

(http://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/beyondsteel/),

which has been ably curated by Lehigh University's Julia Maserjian.

[12] For a preliminary account of the organizing MARCH did at the site,

see Sharon Ann Holt, "History Keeps Bethlehem Steel from Going off the

Rails," The Public Historian 28 (Spring 2006): 31-46.

[13] Kenneth T. Jackson, Lisa Keller, and Nancy Flood, eds., The

Encyclopedia of New York City, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2010); and James R. Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L.

Reiff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Chicago, (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 2004).

[14] Neal R. Peirce, Citiestates: How Urban America Can Prosper in a

Competitive World (Washington, D.C.: Seven Locks Press, 1993).

[15] Supported with funds from the New Jersey Council for the

Humanities, the Camden Clemente courses were part of a national program

administered by Bard College and detailed at

http://clemente.bard.edu/about/.