Class News

Bob Kaiser ’64 writes an op-ed in the Washington Post on our legacy

To the Class of ’64, let’s hope our grandkids do better than we did

Born in the age of FDR and now gathering for a reunion in the time of Trump, it’s hard to argue that we’re leaving the world better than we found it.

By Robert G. Kaiser

May 25, 2024

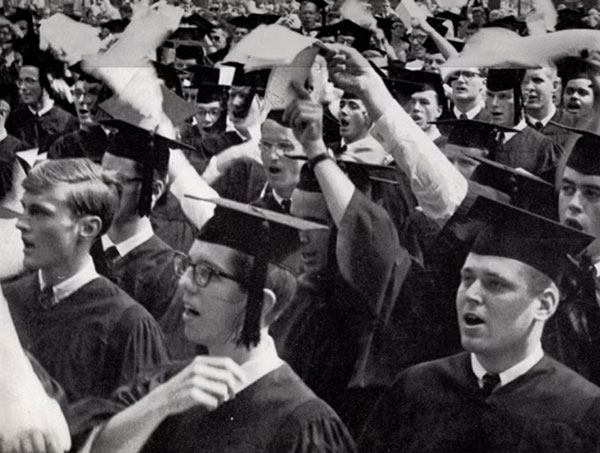

Yale graduation in 1964

When I was asked to write an essay to mark the 60th reunion of the Yale Class of 1964 — proposed title “Where Do We Go From Here?” — I suppressed a laugh. I’m sure we have all figured out that the 700 or so of us still living are headed relatively soon to the same final destination already reached by more than 300 of our classmates.

Bob Kaiser, ’64

But the direction of America and the wider world was the real topic of interest. Of that, I can only guess. It’s a cliché to say so but we really are heading into uncharted territory without a compass. We’ve lived through amazing changes in our 80-plus years, but the next 80 years will surely produce even more profound changes around this deteriorating planet. America will be reconfigured demographically, and much will be transformed by new technologies. Most compelling may be the need to adapt to a radically changing climate. Adjusting to a world where machines may be smarter than human beings will also be an enormous challenge, as will the constant need to resist using thermonuclear weapons.

The world’s inability to establish a global regime to control nuclear weapons and discourage their proliferation after 1945 is one of humanity’s many failures in the lives of the Class of ’64. Frankly, we don’t have a great deal to be proud of. We had our turn at running the world, and our record stinks. Born into the world of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, we are leaving to our heirs and assigns a world that featured Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, a veritable clown show.

But the picture is never clear or consistent. Our time and the future will share an important characteristic that has been part of every era of American history. Past, present, and future have been or will be riddled with contradictions. The earliest version of the United States featured Washington, Jefferson, and Madison — and human slavery. Those three godlike Founders bought, sold, and exploited other human beings, yet with straight faces declared that all men were created equal.

Uplifting moments have jostled with depressing ones throughout American history. It has never been easy to make sharp distinctions between good times and bad, and it probably won’t be in the future, unless our descendants really do burn up the planet or Trump and his cult really do destroy American democracy. If someone had told us in 1964 that these disasters would both become realistic possibilities in our lifetimes, who would have believed it?

When such gloomy thoughts get me down, I often try to recall words of the great Yale professor Vincent Scully, who was much more than an art historian. I was in the audience at the Kennedy Center in 1995 when Scully gave his brilliant Jefferson Lecture. Most of the rhetoric I have experienced in a long life has washed over me like a morning shower, but Scully’s words made a deep impression. I quote them to myself and to friends on occasions when the world’s follies erode my spirits.

Scully recalled “the three great movements of liberation which have marked the past generation: Black liberation, women’s liberation, gay liberation. Each one of those movements liberated all of us, all the rest of us, from stereotypical ways of thinking which had imprisoned us and confined us for hundreds of years. Those movements, though they have a deep past in American history, were almost inconceivable just before they occurred. Then, all of a sudden, in the 1960s, they all burst out together, changing us all.”

The Aga Khan, right, talks with Vincent Scully and his wife, Catherine Lynn,

at the National Building Museum in 2005

Scully understood the significance of these liberations, and we should, too. They were the sort of spontaneous occurrences that bubble up exuberantly from a complicated, self-governing society, often without warning or planning by powerful individuals. There could be more such rebellious upheavals in years to come that would seem as unlikely to us today as legalizing same-sex marriage would have seemed to us on our graduation day in 1964.

One possibility is a rebellion against economic inequality in some future version of the society whose citizens have long been told they were created equal. America is wildly unequal in terms of both income and wealth, and the inequality in both is steadily increasing. Consider:

At the time of our 20th reunion, the median wealth of upper-income Americans was about $344,100; the median wealth of low-income families was $12,300. By 2021, the wealth of typical upper-income families had risen to more than $800,000, and that of low-income families had risen to only $24,500. The richest 1 percent of American earners in 2020 made 104 times as much as the bottom 20 percent.

One more interesting statistic. The top income tax rate when we entered Yale as freshmen (men only, one winces to recall) was just over 90 percent; today it’s about 40 percent. Theoretically, it would be pretty easy to narrow American inequality using the tax code.

But that would require political action, and the rich have big advantages over the lower classes in the political arena. Spending money on campaigns, the Supreme Court has ruled, is the same as speaking out for or against particular candidates: Free speech is the same as free spending, says Citizens United. That’s another potential target for a future uprising.

Of artificial intelligence, the latest technological wonder, I can make no forecasts with confidence. Will the future world delight in AI’s ability to find cures for diseases, ways to reduce the burdens of work, and avenues to fun and fulfillment? Or will AI destroy our confidence in everything from banking to news reporting by supercharging the dark side of human nature, turning us into a nation of fraudsters, phonies, and liars?

The traditional way to end an essay like this one is with some variation of “stay tuned.” As Mort Sahl, a great satirist of our youth, pronounced solemnly: “The future lies ahead.” Indeed it does, but sadly, our lives do not. Our futures are behind us now. As we pass tomorrow’s perils and promises to our descendants, I am hoping that they do a better job than we did.

Robert G. Kaiser is a former managing editor of The Washington Post who worked for the paper for 50 years.